Sweat and rain dripped from my body as I shivered in the predawn gloom of the Guatemalan cloud forest. The hour-long 1,000-foot climb in the dark had tested my stamina and nerves. Now I panted from the thin air of my 7,000-foot perch, or maybe from relief at being safely in my makeshift photo blind, safe from the slick mud reeking of rot, the night calls from night creatures, and shapes moving outside the cone of light from my head lamp. I was waiting for dawn when Guatemala’s elusive national bird, the resplendent quetzal, would begin feeding the chick nestled in the hollow tree before me.

I waited. Slowly the cloud forest shapes formed in the gray mist of dawn. I waited. The colors of the orchids gradually emerged. I waited. My stomach growled, and I ate the cold, homemade corn tortillas. After three hours with no quetzal, I was worried. After five hours, I was depressed. After eight hours, I gave up. The birds were gone. The chick must have fledged in the 24 hours since we finished building our blind.

Once the chick flies, the adults leave the nest, too. Weeks of scouting the steep mountains of the cloud forest for nests and five nights of building the blind without disturbing the birds were for nothing. I had supporting photographs of the birds, but I lacked the beauty shot, the direct quote, the nut graf photograph that would excite the imagination of the viewer. I’d spend the next few days scrambling to find another nest and, if successful, several nights building another blind.

I’d done everything right and, still, in my initial attempt, I failed. That happens in environments where animals operate with their own set of rules. As I sat cursing my luck, I recalled the circuitous path I’d taken to arrive at this place. Doing this work was so very different from my newspaper days of photographing spot news, sports, politics and environmental portraits.

Becoming an Environmental Photojournalist

In some ways, I have the Pacific salmon to thank for this transition. My 10-year project on salmon and the cultures surrounding this fish catapulted me from newspaper work to becoming a freelance photographer for National Geographic, Smithsonian and other magazines. Along the way I received an Alicia Patterson Foundation (APF) Fellowship, the Scripps Howard Edward J. Meeman Award, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in specialized reporting. In time, my photographs and words about salmon were published in my first book, “Reaching Home: Pacific Salmon, Pacific People.”

Many editors consider me a nature and wildlife photographer. I think of myself as a photojournalist whose work explores the increasingly complex relationship between people and the environment. In my salmon project, the fish served as the thread that wove together the many cultures around the Pacific Rim. Documenting how humans use and abuse the earth’s resources was a critical theme in my coverage, second only to the life history and ecosystem importance of the salmon. Even the story of the quetzal included the native people, the Q’echi, their rich culture, and the negative impact their farming had on the bird’s dwindling habitat.

Environmental stories are especially challenging for a photojournalist to tell. While a reporter can write an article without cooperation from the subjects, a photographer must have access to do the story well. In the summer of 2001, I shot an assignment for Mother Jones. The writer was looking at the impact Atlantic salmon farms had on wild Pacific salmon in British Columbia. In the mid-1980’s entrepreneurs province. Rather than catch wild Pacific salmon when they returned to the rivers, these farmers would raise Atlantic salmon, a non-native species, in salt water pens and harvest them when the market demanded. The Canadian government saw it as one way to employ out-of-work loggers.

Many environmental concerns had been raised about farms during the 15 years that I’d been observing the salmon. Some had proven true. But the discovery that large numbers of sea lice were attaching themselves to out-migrating juvenile salmon swimming by the farms was alarming. Just a few lice could kill the two-inch long fish. Many salmon were carrying more than a dozen. Some scientists believed this epidemic, if left unchecked, could doom the region’s wild salmon. Based on evidence from Europe, the researchers suspected that the Atlantic salmon farm net pens were inadvertent incubators for the sea lice.

I contacted the salmon farm industry association to request access to the farms. They declined to help. Once I was in the field, however, it was a different story. Two workers approached me as I photographed the net pens from a skiff. We talked at length about the Mother Jones article, farming issues, and wild salmon. Eventually, they invited me onto the farm to photograph their activities. In this case, my depth of knowledge and understanding of the issues gave me credibility with the workers and added layers to my coverage for the magazine. But few environmental photographers have the time it takes to fully comprehend the complex web of issues involved in any environmental topic.

The Difficulties of Photographing Nature

Those who photograph nature and the environment have separated into many different factions. Some photographers view their work as the opportunity to advocate a certain position; others feel it is only important to get good photographs of wildlife. Some make their living as environmental photographers, but there is a growing number of advanced amateurs who just want to be in nature. With more advanced automatic and digital cameras, the increase of disposable income and rise of ecotravel, amateurs are sometimes producing photographs that rival the pros.

This surge of interest in environmental photography is not without its problems. Anyone who reads popular photography magazines knows when and where to go to photograph bears, whales, eagles, puffins and every other kind of photogenic creature. Some photographers, pros and amateurs alike, believe in getting the picture no matter the costs. Nature is their Disneyland; all they need to do is pay the price. It is a dangerous concept.

This crush of humanity is certainly impacting the animals’ behavior. Each summer orca whales feed on salmon in the waters between Washington State’s San Juan Islands and Victoria, British Columbia. Tourists come to see the whales with as many as 100 boats—of all shapes and sizes—trailing five or six orcas. It is now nearly impossible to get a clean shot of a whale.

But what’s worse is that scientists believe the number of boats, combined with a decline in the salmon and high PCB’s in the whales’ blubber, have resulted in a loss of 11 individual whales in the past six years. The amount of time the whales have to bulk up on the fat-rich salmon is only a matter of weeks and, as the runs decline, any time spent away from feeding might be harmful. Canadian researchers have found that whales swim faster and change their diving patterns when boats approach. Are we reaching a point where we are loving our animals to extinction?

Far from the bumper-boats in the San Juans are the wildlife photographers who stay in tents, eat bad food, and live without the luxury of showers or toilets in order to fully document the behavior of these incredible creatures. These are images that can advance our understanding of the world’s creatures. Unfortunately, the amount of money supporting such important photographic work is declining.

In the golden days of the 1970’s and 1980’s, magazines like National Geographic and German Geo supported months-long assignments about the environment. I am grateful to Tom Kennedy, former director of photography at National Geographic, for giving me an assignment with which I completed the salmon work I had begun with my APF Fellowship.

Early in the 1990’s, budgets were cut. The length of most assignments was reduced to weeks. Then magazines discovered it cost them less to buy the licensing rights to a story already photographed than to pay a photographer’s fees and expenses. Editors would know what they were getting and avoid the possibility of an expensive failure. The burden of financing the story was shifted to the photographer. Many of us grudgingly accepted this new paradigm because we wanted to tell these important stories. We used funds from our business or our savings to underwrite the stories. At the same time licensing fees for these images remained the same or even declined while the costs of doing business increased. Some photographers have been driven out of business.

Using Innovative Techniques

But the most serious problem facing environmental photographers and writers is the numbing of the public to the complexities of environmental stories. Rhetoric designed for a 30-second sound bite has had a polarizing effect on the public.

The coverage of the Bush administration’s recent forest plan is a good example. In the aftermath of the devastating western wildfires, President Bush proposed thinning trees and underbrush as a way of lessening the risk. He condemned environmental lawsuits and stated that they had prevented the government from removing the underbrush in the past. His new policy would prevent future legal challenges. The insinuation was that the environmentalists were in part responsible for the fires.

Television and the local Seattle newspapers covered the pre-announcements of the policy as well as the President’s speech. It was not until I read the next day’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and watched public television news later that night, that I learned the government’s General Accounting Office had found and reported that environmentalists had challenged fewer than one percent of these projects. They had gotten a bad rap that would be nearly impossible to correct.

Distrust and demonization cut both ways. Many of my friends and colleagues are convinced that the only good logger is an unemployed logger. They are astounded when I tell them that some of the most rabid conservationists I’ve interviewed worked in a logging camp in Alaska.

So how do we help foster a better understanding of environmental issues? First, put away the rhetorical white and black hats and bring the debate back to the issues and away from the politics or personalities. Don’t be content with covering only the superficial. Assign photographers and reporters to areas of interest and let them learn about their specialties. Assign more space to articles about the environment.

Environmental photojournalism will become even more important in the future as our society struggles with the escalating depletion of our once vast natural resources. The challenge for photographers will be to create evocative images that tell the story of what this loss means. And as photojournalists seek out these images, headshots of bear, walrus or salmon won’t make it in this era of flash, pop and increasing visual sophistication.

Real decisive moments, not captured in animal farms but rather in the wild, will always captivate us. But there are new photographic approaches that stimulate our thinking, too. In his groundbreaking and successful book, “Survivors: A New Vision of Endangered Wildlife,” James Balog photographed animals in a studio. Unlike photographers who hire captive animals and pose them in the wild to create natural-looking images, Balog went out of his way to photograph them in a very unnatural environment. He wanted to force the viewer to concentrate on the magnificence of these endangered creatures.

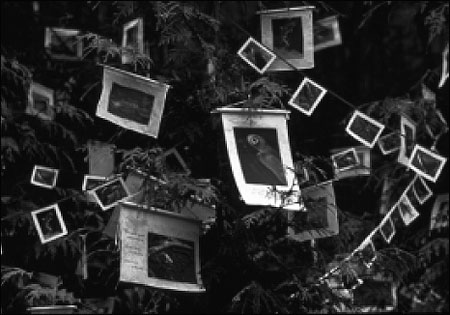

In my exhibit, “Salmon in the Trees,” I printed my salmon photos and poems on flags and hung them from the trees near a salmon stream in a Seattle Park. The theme was the importance of salmon to the forests. It is another example of how photographers can get their message across in a nontraditional way.

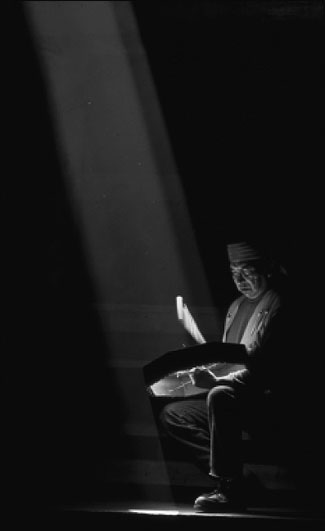

Different photographic techniques and formats also surprise the eye. Some photographers hand-color their black and white prints to create images with a hint of mystery. Others use wide-format cameras to capture unpredictable angles. In my second book, “I Dream Alaska,” as well as my Orion article about the Exxon Valdez oil spill, I printed my images with the Polaroid transfer process. To do this, I first take a Polaroid photograph of a slide. I then pull the negative from the film pack before the print is fully developed and lay it on a sheet of paper. The dyes transfer to the paper, creating an image with a timeless watercolor quality.

We must strive to creatively catch the public’s eye while we remain true to our journalistic roots. If we don’t, we are in danger of becoming the Galapagos Islands of the visual world—interesting, intriguing, but totally removed from the real world.

Natalie Fobes, a photojournalist, specializes in photographing cultures and wildlife around the Pacific Rim. Her photographs have been published by National Geographic, Geo, Natural History, and Audubon. She was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in a writing category, won the Scripps Howard Meeman Award, and received an Alicia Patterson Fellowship.