A popular traffic app could show you the queues building up at border crossings between Russia and its neighbors back in September, as young men evading mobilization sought to escape the country.

Apple’s Find My tool can show you where that Russian soldier who stole a local’s headphones ended up.

A heat signature tracker can show you where fires rage in the warzones of Ukraine’s east and south.

Satellite imagery starkly comparing Ukraine’s cityscapes before and after Russian airstrikes is now a regular fixture in the news.

More than nine months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the online methods for tracking this war are many and proliferating, including the most obvious source of all — social media networks. A 2019 law designed to keep its military from posting on social media has not deterred Russian servicemen from sharing images and updates from the frontline, not least on Telegram and the Russian social network VKontakte, potentially allowing anyone with an Internet connection to pinpoint the place, time, and sometimes individuals seen in footage of military movements.

Open-source investigations (OSI), popularly and misleadingly known as open-source intelligence, is not synonymous with social media, however. OSI is any information that can be publicly accessed by others, including but not limited to online sources. That includes everything from local newspapers to satellite imagery and images shared on TripAdvisor. What it doesn’t include are two mainstays of traditional investigative journalism — non-public document leaks or closed-source reporting, otherwise known as shoe-leather reporting and interviews.

Over the past few years, newsrooms have started integrating open-source methods into their coverage and building their own OSI teams. That’s in part to verify social media posts, and in part to report on places where it is simply too dangerous for journalists to venture — areas on or behind the frontlines — where open-source imagery allows a glimpse into military movements and potential war crimes. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, open-source investigations have surged in prominence and the genre as a whole has attracted scrutiny, not least from state actors themselves.

Rising awareness of what open sources can yield has motivated journalists to do more than simply verify what they find online. Several newsrooms now have dedicated open-source teams, like The Washington Post’s visual forensics team and the BBC’s Africa Eye, which recently used social media images to reconstruct the scene of a horrific clash at the fence surrounding the Spanish enclave of Melilla’s border with Morocco, in which 24 migrants were killed. There’s also The New York Times’ visual investigations unit, which in April used satellite imagery to debunk Moscow’s claims that bodies had been placed on the streets of Bucha after Russian troops had withdrawn from the Ukrainian town.

Open-source newsgathering is becoming integrated into journalistic practice as a standard reporting technique, particularly in investigative newsrooms. The divide between open-source investigations in the form of online research and closed-source investigations may turn out to be a generational one. For young journalists who have been socialized online, the Internet has always been a source of public interest information.

A Brief History of OSI

Until fairly recently, access to high-quality satellite images was mostly the privilege of governments and commercial actors with deep pockets. Today, detailed satellite imagery costs just hundreds or even tens of dollars. This new accessibility may well be due to an expanding market of mid-range buyers with shallower pockets than traditional procurers of satellite imagery, according to my colleague Nick Waters, an open-source analyst at Bellingcat. The past decade, he says, has seen a rise in commercial resellers of satellite imagery as well as platforms such as Planet, which offer significantly cheaper packages than competitors like Maxar and Airbus. Technological advances, too, allow for smaller components in satellites, which allow such companies to launch them in larger numbers.

Before these changes, the techniques and processes needed to analyze such images existed but were seldom pursued publicly and in the public interest. Corporations could use them to scour the earth’s surface for signs of hydrocarbons or minerals; governments could take stock of their opponents’ airstrips or military emplacements. They still do. But now, so can everybody else.

Open-source research used to take place at both ends of the resource spectrum. At one end, state actors and corporate due-diligence departments vetting new employees or compiling risk assessments for investors; at the other, social media hobbyists with lots of time and patience scouring images and videos to fact-check claims made by parties in various armed conflicts. Theirs was a smaller community confined to mailing groups, forums, and independent blogs rather than the largely Twitter-dominated open-source volunteer community we know today.

Around a decade or so ago, early news aggregator sites started to fill the space in-between. Storyful, founded in 2010, offered a service akin to an open-source newswire, verifying and contextualizing social media posts to a standard that traditional news media could then incorporate in their reporting — later offering its own open-source investigative services. Collectives like Forensic Architecture, also founded in 2010, and Bellingcat, where I work, founded in 2014, turned these techniques towards egregious human rights violations in a manner more like the research department of a watchdog NGO than a traditional newsroom.

Bellingcat’s first big scoop, for example, concerned the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 in July 2014. Founder Eliot Higgins and other volunteers examined social media footage to corroborate claims that a BUK missile launcher operated by pro-Russian militiamen had fired from occupied Ukrainian territory on the day of the attack. This doggedness also took aim at Russian state actors’ attempts to obfuscate and derail this line of enquiry, most notably in apparently doctored satellite imagery presented at a press conference in July 2014 by the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Journalists have used open sources in coverage before. In 2013, The New York Times’ C.J. Chivers and Eric Schmitt followed up on Higgins’ documentation of small arms being used in the Syrian Civil War to produce a longer article on how Yugoslav-manufactured weapons made during the Cold War were making their way to that conflict. The first clues to the existence of the Xinjiang internment camps were discovered by the German academic Adrian Zenz, in the form of construction tenders publicly available on local government websites that corroborated rumors of a new mass incarceration system. In several cases, the size and location of these facilities could then be verified with satellite imagery and were consistent with survivor testimony.

In the tense weeks before Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion, open-source imagery — showing the incremental buildup of a significant Russian military force along the borders of Ukraine — was the basis among the commentariat for a battle of interpretations as to Russia’s ultimate objectives.

When Russian tanks crossed into Ukraine, open-source analysts saw a surge in followers, although the generational shift in the field could be felt in the increased importance of a wider range of social networks, most prominently TikTok, as a source for footage of Russian military equipment on the move. Most reporters online following the war now know the intricate maps compiled by Nathan Ruser, based on open-source evidence of military movements on the frontline as well as geo- and chronolocated footage posted on social media networks, particularly Telegram. They know the pseudonymous Oryx Spioenkop, who famously counts Russian tank losses (and their conversion to Ukrainian tank gains), and the ship spotter Yorük Işık, who tracks maritime movement through the Turkish straits. These names now feature prominently in news and investigative reports.

How OSI Works

On June 27, reports appeared that the Amstor shopping mall in the Ukrainian city of Kremenchuk had been hit by a Russian missile attack. Reports of high casualties followed, as did dramatic images of the building ablaze. Just as quickly came a flurry of deflections and denials from Russian officials and state media channels. The mall wasn’t hit, they claimed, but caught fire after a missile strike on a nearby facility repairing Ukrainian military vehicles where ammunition was stored; the mall was hit but because it was actually a clandestine military facility; the mall was hit but it wasn’t open that day so there was no question of deliberate targeting of civilians; the mall was hit but the fact that Ukrainian soldiers appeared on the scene alongside emergency services raised questions as to its purpose.

These kinds of responses were familiar to anybody who had witnessed the reaction of Russian state media channels following the shooting down of flight MH17 eight years earlier. The purpose was presumably not to convince anybody of the merits of these false arguments but, like similar “fake news” strategies used by politicians and governments, to muddy the waters, to advance an epistemological nihilism. Open-source evidence showed the truth.

While journalists in Ukraine for The Guardian and CNN were able to visit Kremenchuk and interview eyewitnesses, Bellingcat quickly verified and analyzed all open-source imagery we could find relating to the event. A CCTV video from a nearby factory posted to social media showed the moment of the explosion as locals strolling in a park fled for cover. There were no secondary explosions from neighboring buildings, as would be expected if an ammunition warehouse had been struck. No significant impact site could be seen anywhere near the mall, undermining claims that a fire spread from the factory area.

Russian media had claimed that a lack of activity and reviews on Google and a lack of images from inside the mall proved that the building was closed at the time of the strikes. But the social media pages of various businesses based at the Amstor mall had posted announcements welcoming their customers back on June 25. These later offered messages of condolences to their employees who had been killed or wounded in the attack.

The same pro-Kremlin media outlets opined that the lack of vehicles in the mall’s car park in the footage of the aftermath also proved that the mall had been closed. But satellite imagery Bellingcat reviewed dating back to 2016 showed many occasions during opening hours when the parking lot had been sparsely occupied. Moreover, online mapping services and guides to Kremenchuk put the Amstor mall well within walking distance of bus and trolley stops. One Ukrainian even posted a receipt for a purchase made at the mall shortly before the attack, showing the date, time and address of the mall — a key piece of evidence that widely circulated on Twitter.

None of us working on the Kremenchuk missile strike set foot in Ukraine that day. But we reached the same conclusions as journalists in-country, such as The Guardian’s Lorenzo Tondo, who cited our findings in his report from Amstor. What makes an organization like Bellingcat unique is no longer that we produce open-source investigations, but that we use exclusively open-source information in our investigative process.

“The successful integration of open source into journalism requires humility about the limitations of the genre, an acknowledgement of what information cannot be obtained from open sources, and how traditional reporting methods must be used to obtain that information”

Kremenchuk was one of several cases where Bellingcat employed open-source research to debunk specific, contradictory Russian claims designed to deflect scrutiny. But the excitement for open source can lead to extravagant expectations for the genre. A ‘footage fetish’ — a phrase coined by Jeremy Morris, professor of global studies at Aarhus University in Denmark — is taking hold on social media. It’s more important than ever to remember that a single image rarely tells the whole story. A case in point is Ukrainians’ adherence to their government’s request not to post images and videos of the Ukrainian military on the move — leaving an important gap in what open-source research alone can contribute to comparisons between the Russian and Ukrainian forces. The successful integration of open source into journalism requires humility about the limitations of the genre, an acknowledgement of what information cannot be obtained from open sources, and how traditional reporting methods must be used to obtain that information.

Open-source sleuthing will not — and should not — fully replace traditional reporting. In fact, some of the finest investigative journalism on Russia’s invasion has come from the union of the two genres. In May, a spraypainted Instagram handle in a house in Bucha gave one Reuters journalist a further clue as to the Russian unit present during the massacres in the occupied Ukrainian town. Later that month, The Wall Street Journal combined local news reports, on-the-ground interviews, and dash cam videos filmed by locals to show how Russian forces had fired on civilians traversing the “road of death” west of Kyiv.

Residents of the town of Motyzhyn told the Wall Street Journal that they had been deliberately fired upon on this perilous four-mile road. Journalists later analyzed mortar fragments — they were a type that has a range of between two to five miles — found at the locations identified by the civilians. A local in the town who had shared a firing location with Ukrainian territorial defense units shared the information with reporters. This location was not only within the range of the aforementioned mortar type but had seen heavy Russian military activity in the timeframe civilians mentioned coming under attack.

This forested area yielded mass graves and the detritus of Russian military soldiers’ encampments, including badges from the 37th Guards’ Motor Rifle Brigade. A creative confirmation of Russian military activity was provided by the family of Oleg Moskalenko, a local who was detained by Russian soldiers at an impromptu checkpoint along the road that was threatened by Russian fire from the north. During his absence, his relatives traced his iPhone to the grassy area north of the road using the Find My function.

The Ethics of OSI

There is doubtless much more to discover, whether in the dormant social media accounts of dead soldiers or the CCTV cameras with a vantage point on a missile strike. A primary concern today is what to select from the deluge of publicly relevant information emerging from hotspots — a problem at least as important as how to extract meaning from what is selected. Knowing the technical shortcuts to finding useful data — scraping social media channels or filtering posts by geotags — is a key asset, necessary even before acquiring verification, chronolocation, and geolocation skills.

Yet these new methods bring with them new editorial and ethical questions about applying journalistic best practice.

Open-source research offers journalism the promise of a participatory model that could, in theory, help enhance trust in the media, which has been in steady decline for more than a decade. At the heart of open-source research is the hope that audiences can, if they access the same materials, follow the same steps and reach the same conclusions as the journalists did. This is the essence of the “show your work” principle — sharing source documents, publishing full transcripts of interviews — that many news outlets now make a routine part of their reporting.

Journalists’ pleas for public input to complete their stories are not new. In 2010, amid growing enthusiasm for the rise of citizen journalism, The Guardian’s Paul Lewis took to Twitter to appeal to airline passengers and later for their ticket stubs. He was seeking anybody who had witnessed the death of asylum seeker Jimmy Mubenga, who lost consciousness while being restrained on a British Airways plane bound for Angola.

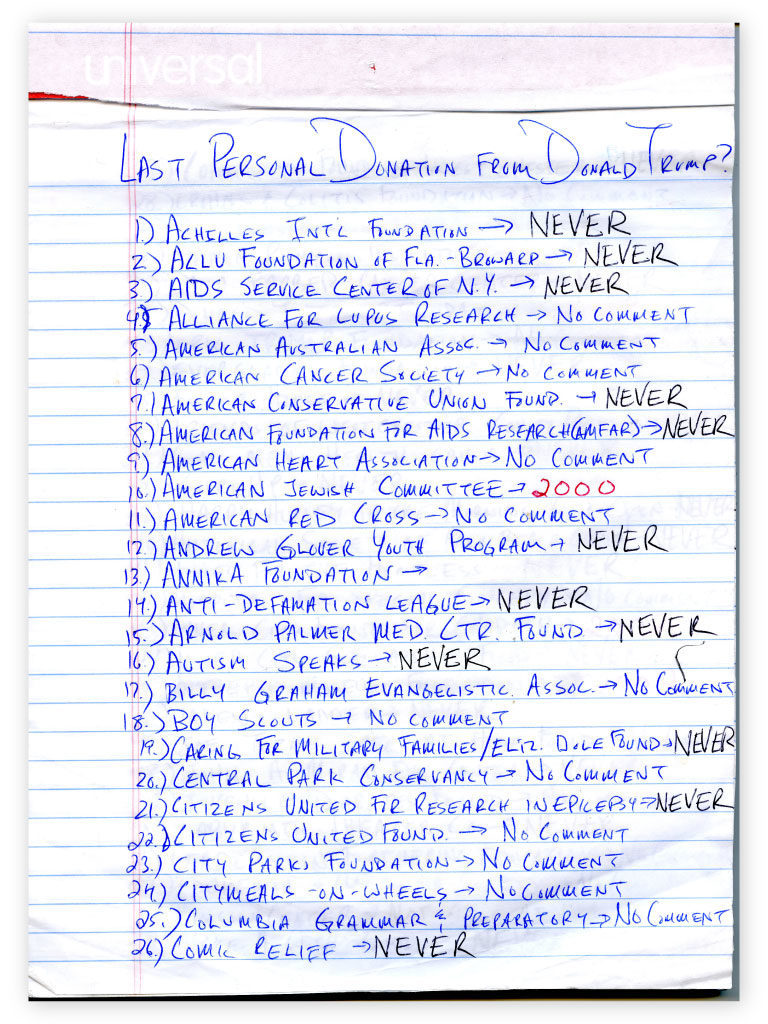

In 2016, David Fahrenthold, then with The Washington Post, pieced together Donald Trump’s charitable giving through a mix of old newspaper clippings and New York State tax filings to compare Trump’s public statements about his foundation’s philanthropy with hard data. When Fahrenthold began contacting hundreds of charities to see if they’d gotten donations from Trump, he took pictures of his notes and shared them on Twitter to see if he was missing anything. The result was a comprehensive look at how Trump used his charitable donations to purchase art and other items for himself.

A recent Reuters Institute study found that many of today’s news consumers implicitly trust visual media more than text, a finding that should be very promising for open-source journalism. But open-source intelligence does not always speak for itself. It often needs contextualization and interpretation. Images of rows of burnt-out tanks alone may mean little to readers, and even less when the open-source researchers do not state clearly how they verified the image.

Even when open-source research is not paired with shoe-leather reporting, it still needs thorough vetting. One example is the extensive use of expert comment by BBC’s World Service Disinformation Team in debunking Russian state media claims that Ukraine was selling weapons provided by NATO on the black market. A standard reverse image search revealed that photographs that ostensibly showed weapons for sale were in fact several years old and had previously appeared on a gun enthusiast’s website in 2014. But reporters also noticed that these purportedly Ukrainian channels had misspelled Kyiv in Ukrainian, a clue that prompted them to go undercover and contact the site administrators posing as a buyer. Their interlocutor also made significant errors in Ukrainian. According to a linguist interviewed by the journalists, these mistakes suggested the messages had in fact been written by a Russian speaker with the aid of translation software. Without this expert comment, such an editorial observation may have seemed highly subjective and speculative, undermining trust in both open- and closed-source components of the reporting.

In today’s open-source journalism, transparency of method and transparency of sources are even more tightly braided together. After Bellingcat’s December 2020 investigation into the poisoning of Russian opposition politician Alexey Navalny, which implicated members of Russia’s Federal Security Services (FSB), we decided to make public a spreadsheet containing the travel data of members of the poison squad. Several members of the public soon noticed correlations with the mysterious deaths or severe illnesses of a number of other opposition activists in Russia — from a local activist in Dagestan to the celebrated Russian poet Dmitry Bykov. Thus, an entire series of investigations was born. Our readers had not just contributed to the story but determined what that story would be.

The Limits of OSI

Open-source materials on which readers are meant to base their enhanced trust must occasionally be redacted or removed, sometimes by editors and sometimes by the platforms where the materials are discovered. That potentially undermines a key appeal of open-source intelligence — the promise of a new, radically transparent relationship between reporter and reader.

When it comes to footage, this participatory model can be complicated by platforms’ attempts to become more responsible content moderators. Posts from warzones that are relevant to journalists are removed because they often breach policies on depictions of violence. So, when this kind of material is deleted, the unconvinced reader may still have only the journalist’s word that relevant posts ever existed, potentially undermining transparency.

But best practice can also dictate that journalists sometimes refrain from being fully transparent about source material. In several European jurisdictions, media generally refrain from publishing the faces of private individuals suspected of but not officially charged with a crime.

Bellingcat obscures much of the extremist, incendiary social media posts we encounter in our reporting on far-right online subcultures, in line with best practice laid out in the Data Society’s 2018 Oxygen of Amplification report. This decision stems from a desire not only to avoid inadvertently amplifying hate speech, but to instead emphasize its context, discourse, and spread in order to redirect the focus away from that preferred by extremists. As we know from reporting on the far-right in North America, fascist groups are particularly adept at gaming the system, parrying and provoking the news media into rewarding them with notoriety and free publicity. The same questions could be asked of the need to gratuitously reproduce the hate speech made by Russian television pundits and nationalist bloggers towards Ukrainians.

This dilemma is even more acute when faced with distressing footage that may depict war crimes. In February, Bellingcat reported on a series of apparently staged videos recorded by pro-Russian media channels in the run-up to the war. In one gruesome example from the Donetsk-Horlivka highway, a cadaver showing signs of a medical autopsy had been placed in a burnt-out vehicle; Russian journalists asserted that the body belonged to a local civilian killed by a Ukrainian improvised explosive device (IED). My colleagues noted a neat cut through the skull cap of one of the corpses in the vehicle, which a forensic pathologist told us was consistent with an autopsy procedure. This indicated that the body was likely placed in the vehicle before it was set alight. We chose not to embed links to the full, extremely graphic content and to obscure sections of imagery we had to publish in order to show the top of the skull in question.

In August, we reported on one of the most disturbing videos of the conflict, posted on Russian social media from the frontline near Pryvillia, depicted a group of Russian paramilitary fighters mutilating and then executing a captured Ukrainian soldier in an act of horrific sexual violence. We chose not to link to the video and obscured disturbing elements of screenshots presented for analytical purposes — in this case, features which allowed us to connect two videos believed to be taken at the same spot as well as those that allowed us to eventually geolocate both to the crime scene. These features were not only visual: In describing the video, we omitted several extremely disturbing details about the act of sexual violence depicted, which were not essential to the purpose of the analysis.

There are a growing number of resources dedicated to the ethics of open-source research in media. A recent report from the Stanley Center, a policy organization dedicated to peace and security, includes a comprehensive workbook designed to introduce researchers to conundrums loosely based on real examples, for example. Some of these, such as a researcher considering whether to use a “sock puppet” account to view a closed social media profile, broadly echo traditional journalistic debates about the ethical limits of what can be done to secure access to crucial sources. Others, such as a manager considering the ethical responsibilities of requesting her employees to review hours of graphic material online, are perhaps more novel. In the context of Ukraine, the latter can have broader implications for readers, too. Frank conversations about the need to share extremely graphic evidence of war crimes need to be held, especially when Russian state actors and conspiracy theorists repeatedly deny such evidence.

The consequences of poorly conducted OSINT analysis can be severe. In the case of the disturbing video from Pryvillia, there were very few visual clues to conclusively identify the culprit in the mutilation scene itself, though the face of a man wearing the same clothes as the culprit could be seen in other videos taken in the same area with the same Russian paramilitary unit. Crucially, this man was one of the few of East Asian appearance in footage of these soldiers, likely a member of an ethnic minority from Siberia, Russia’s Far East, or areas of the North Caucasus. On this basis, some open-source researchers used facial recognition websites that incorrectly identified a man from Russia’s Republic of Kalmykia in the North Caucasus as the suspected culprit. The likely culprit, Bellingcat and partners ascertained, actually came from southern Siberia.

In Ukraine, this facial recognition process often involves Russian search engines, such as FindClone, which then attribute a name and social media page link to the identified face. Researchers should be careful never to rely wholly on facial recognition for identification given the possible ethnic and racial bias, as studies have found on U.S. examples with Black faces. Nevertheless, the incorrect identification circulated widely, a testament to the high stakes of online misinformation. The actual suspect was later sanctioned by the U.S. authorities.

Then there are the risks Ukrainians themselves face. Ordinary Ukrainians are increasingly waging their own war with digital tools and drones. But footage is geolocatable, and they risk becoming targets for prosecution or worse, particularly in occupied territories. These risks place a palpable ethical burden on newsrooms, which are the first to amplify such footage. For example, in Bellingcat’s interactive map of incidents of harm to civilians in Ukraine, my colleagues have partially obscured the geolocations of footage when it is believed that the authors could be endangered if their identity was revealed.

An awareness that the fruits of their research can translate into real action against people perpetrating possible war crimes may draw even more enthusiasts towards these open-source methods

Footage of these horrors — not only potential war crimes but the cumulative drip of suffering in the form of destroyed schools, crying refugees, and homes ablaze — can present a psychological risk to volunteer researchers and members of the public who may not benefit from the same institutional support afforded journalists. Yet these same researchers are increasingly an invaluable resource to mainstream journalists. Concerns about secondary traumatic stress — repeated and prolonged exposure to the trauma of others — has prompted my colleagues to either remove particularly disturbing elements of such content when working on it with volunteers or not expose them to it at all.

The horrors unfolding in Ukraine could set an important precedent for the admissibility of online information in international criminal tribunals. An awareness that the fruits of their research can translate into real action against people perpetrating possible war crimes may draw even more enthusiasts towards these open-source methods. This thirst for justice and accountability is the same pull factor that drew enthusiasts towards traditional investigative journalism.

In this sense, open-source practitioners’ openness to collaboration also interrupts traditional journalistic exclusivity, promoting a skillset and methodology that can be and is being employed by the general public. However, in an ideal collaboration with news media, its impact is enhanced not only by the reach of the latter but by the application of ethically grounded journalistic practice. In this partnership, as University of Gothenburg researchers Nina Müller and Jenny Wiik wrote in Journalism Practice in 2021, journalists are “no longer gatekeepers” but “gate-openers,” coordinating different actors with different skills and competencies.

But the process of producing OSINT in newsrooms to journalistic standards takes time, training, and money — things often in short supply. What appears to be a simple geolocation can take hours if not days of paid staff time to verify. Some of the most memorable open-source stories are the fruits of long-established habits of trawling online data about highly specific if not arcane subjects of interest. This can be a luxury to reporters under time and financial pressure. Moreover, the fruits of crowdsourced research from the volunteer community should also be verified in-house. All this takes considerable time, and that time means staffing costs. Open source is no silver bullet.

Established open-source researchers can learn a lot from journalistic best practice, but journalism also has a great deal to learn from the open-source research community. OSINT practitioners are not as proprietorial about their findings as journalists, and they exhibit the collaborative impulse journalists hope will help save their field. Just as the collaboration among journalists also needs to gain equilibrium, so should the relationship between large legacy newsrooms and open-source volunteers who have substantially contributed to their coverage of Ukraine.

Open-source research is also fragile by nature. The wider the publicity for sensitive open-source investigations, the more circumspect social media users become about sharing information that could be in the public interest. The field’s methodological transparency is at once its greatest asset and its greatest hindrance. As open-source research gains prominence, more and more actors will be inspired, and not all of them will use these techniques for the public good.

In autocratic and democratic societies alike, data has become a very valuable commodity for political control or commercial advantage. But governments have been slow to recognize that the surveillance can go both ways. States that collect data about their citizens also collect this data about their own functionaries. The internet is sieve, and in some countries it leaks more than others. Russia’s black data markets, which played the key role in investigating the men who followed and poisoned Alexey Navalny, have thrived in part due to the pervasive corruption in Russia.

But the same dynamic can be found in countries of diverse political systems: As Haaretz has reported, Israel’s data brokers have also come to the fore to sell personal information. Perhaps the greatest ally of an open-source researcher is banal human error by those hunters who believe that they cannot be hunted — the same human error which allowed my colleagues to discover that U.S. servicemen in Europe upload sensitive details about nuclear weapons to publicly available flashcard applications. The hope has to be that OSI will continue to offer a way to hold the powerful to account.

“Back when I started training media in 2013 and presenting open-source techniques, it was as though I was doing magic tricks,” says Eliot Higgins, Bellingcat’s founder. “But now, if you’re not doing it, you’re not doing your job.”