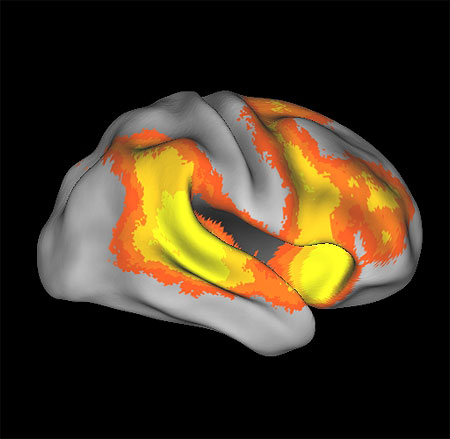

The orange and yellow regions in the brain’s right hemisphere were more active for a group of individuals when they stopped themselves from making a movement. Image by Eliza Congdon.

Russell Poldrack is a professor of psychology and neurobiology and director of the Imaging Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. In his research he uses imaging to understand the brain systems that underlie the human ability to learn new skills, make good decisions, and exert self-control. What Poldrack and his colleagues discovered in their investigations provides information useful to journalists as they look for ways to engage the minds of readers, viewers and listeners through digital media. This past October he began blogging for The Huffington Post about his research. The words that follow are adapted with the author’s permission from two of his blog posts, one about the brain and multitasking, the other about what people recognize about their own learning.

As I set out to write about multitasking and information overload, let me admit that I am an information junkie. It’s difficult for me to make it through an hour-long meeting without peeking at least once at my iPhone to check my e-mail and on more than one occasion I’ve come close to hurling myself down the stairs as I try to read e-mails while descending.

Why do I do things that place me in such clear social and physical peril? Part of the answer lies in the brain’s response to novelty. After all, it is built to ignore the old and focus on the new. Marketers clearly understand this: Watch closely and you will notice that heavily-played television ads will change ever so slightly after being on the air for a few weeks. When our brain detects this change, our attention is drawn to the ad, often without us even realizing it.

Novelty is probably one of the most powerful signals to determine what we pay attention to in the world. This makes a lot of sense from an evolutionary standpoint since we don’t want to spend all of our time and energy noticing the many things around us that don’t change from day to day. Researchers have found that novelty causes a number of brain systems to become activated; foremost among these is the dopamine system. This system, which lives deep in the brain stem, sends the neurotransmitter dopamine to locations across the brain. Many people think of dopamine as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter because drugs that create euphoria, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, cause an increase of dopamine in particular parts of the brain. But a growing body of research shows that dopamine is more like the “gimme more” neurotransmitter.

Kent Berridge and colleagues at the University of Michigan have done interesting studies in which they videotape rats and then measure how often the rats exhibit signs of pleasure—what we call “affective reactions.” Blocking dopamine in the brain turns out not to affect how often the rats exhibit these pleasure responses but instead it reduces the rats’ motivation, turning them into slackers. (Another neurotransmitter system in the brain, the opioid system, seems to be the one that actually produces the pleasurable sensations, though it has very close relations with the dopamine system.)

Dopamine also is very much involved in learning and memory, which occur in the brain through changes in the way that neurons connect to one another. We know that the brain can change drastically with experience. However, the brain needs some way to control these changes; after all, we wouldn’t want our entire visual system to be rewired to see upside down after doing a single handstand. Dopamine is one of the neurotransmitters that controls this: When dopamine is released, it is a signal to the brain that it is now time to start learning what is going on.

So what do things happening inside the brain have to do with the way I behave with my iPhone? Well, it’s hard to imagine a more powerful novelty-generating device. Every time it buzzes to signal a new e-mail or text message it is wiring even more firmly into my brain the desire to pick up the device and look for that precious nugget of new information, which often is only a reminder of another committee meeting. Although no research has yet been published on this, I am confident that we soon will see that our bond to these devices works through the same mechanisms in the brain that govern addiction to drugs, food and many other things.

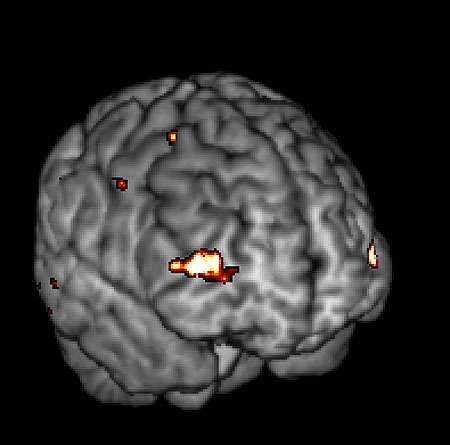

These highlighted regions in the prefrontal cortex were more active when a person silently counted backward than during a rest period. The largest of them is often active when people engage in mental activities that place heavy demands on working memory. Image by Russell Poldrack.

These highlighted regions in the prefrontal cortex were more active when a person silently counted backward than during a rest period. The largest of them is often active when people engage in mental activities that place heavy demands on working memory. Image by Russell Poldrack.Maximizing Learning

There is a second, related question of particular interest for journalists. How can news of importance be effectively conveyed through the digital clutter and information overload to people who are in constant novelty-seeking mode? Key to figuring out how to do this is gaining an understanding of why and how the brain responds to novelty—and then taking advantage of this knowledge in figuring out how to attract attention. However, it is equally important to be sure that once information breaks through the clutter that the person receiving it remembers it.

Unfortunately, our intuitions may lead us astray: Psychological research has shown that people are not very good predictors of their own or others’ learning. A good example of this comes from a study done in 2006 by Henry Roediger and a graduate student, Jeffrey Karpicke, at Washington University in St. Louis. Using two different approaches, they taught students about the sun and sea otters by giving them a paragraph containing scientific information to read about each topic. One group of students had the chance to read the material four times. Another group was given only one chance to read it, then was tested three times on how much they remembered.

Then, through a questionnaire, members of each group told the researchers how well they thought they had learned the material. The researchers also gave them memory tests within a few minutes after studying, as well as one week later so they would have objective data to evaluate along with the students’ own subjective evaluations.

When questioned about how well they had learned the material, the people who had read the paragraph four times indicated that they felt much better about their learning of the material. They also performed better on the memory test right after studying. However, things were very different a week later. At that point, people who had studied the paragraph once and then been tested three times handily outperformed the overconfident paragraph-readers on the memory test for the material.

This kind of research is teaching us that often we can be overconfident about memories that are completely false and yet lack confidence about our ability to remember things we have actually learned well. In particular, we often confuse fluency (or ease) for ability. By its fourth time reading the paragraph, that group found it very easy, and this led them to think that it would be a snap to remember the material later. But it wasn’t.

There is a growing body of research showing that things that are hardest are what make us learn best. This concept is known as “desirable difficulties.” If something is too easy then we probably aren’t learning very much. We have more to find out as we determine just how widely this idea applies. But there is enough evidence already assembled to give us reason to rethink how learning takes place in our daily lives.

The finding of desirable difficulties poses a serious challenge to journalists because things that make people remember best are also things that people are likely to avoid because they are difficult.

As researchers learn more about how learning and memory work, there may be additional clues about how to maximize learning. But there are already some tricks that can be used. For example, information is often remembered better when presented multiple times, but only when those different times are spaced apart from one another. Thus, presenting several versions of an idea in different parts of a story could help improve retention.

If journalism is about learning—about taking in news and information and understanding its relevance to our lives—then what neuroscientists and brain researchers are finding out about the brain and its capacity to absorb information surely matters.

For more information about Russell Poldrack’s research go to www.poldracklab.org.