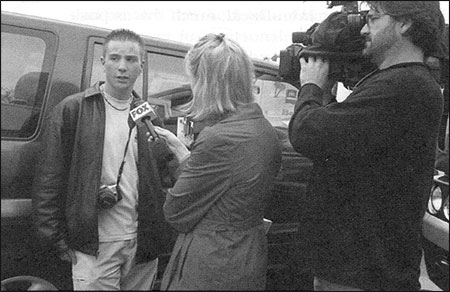

Barbara Schardt’s son, John-David, being interviewed by the media in March 2001. After many days of being interviewed, he told a reporter, “I’m sick of myself.” Photo by Monica Almeida/NYT Pictures.

March 5 began like every other Monday morning, except I was on call. If I didn’t receive a phone call by seven a.m., I’d have the day off. That hour came and went without a call, so my mind turned to thinking about all I could get done that day as I went to get my 17-year-old son, John-David, out of bed. “You have 20 minutes to get to school,” I told him. Our drive to school went as it usually did, with about eight minutes of conversation with topics ranging from what concert might be in town to whether John-David had lunch money or the books he needed. Invariably, he had forgotten either a book or, more recently, his camera, since he was now passionate about photography. We said our good-byes, and I watched him hurry off to class.

Later that morning, John-David called me at home. Before the phone was to my ear, I heard him say, “Mom…there’s been a shooting at the school….” I heard yelling and screaming in the background, then deadly silence. He was no longer on the phone. My heart stopped beating. I had to catch my breath. I hung up the phone, told myself to remain calm and not to panic.

Turn the TV on, I told myself. A local station was doing a live news feed. There had been a shooting at Santana High: Two students were dead, others injured. Students were being evacuated to a staging area across the street. I heard the words without quite believing what I was hearing. I tried calling the school, knowing I wouldn’t get through. I didn’t, and decided to call the sheriff’s department, where they confirmed the news. I made one more call to my former husband in San Francisco, who is a police lieutenant with the San Francisco Police Department. I certainly did not want him hearing about this second hand. He asked me to contact him as soon as I made contact with John-David.

Santana High is only a few minutes from our home. I drove there having no idea what happened to my son. He managed to call me within minutes of the shooting, but I knew nothing more. Was he hiding? Was he in danger? A million scenarios ran through my mind. All I could think about was Columbine and the students who hid out and made phone calls to their parents.

Tears were flowing as I approached the intersection at Mast and Magnolia where emergency vehicles were everywhere. Many parents were on foot, charging toward the school. All of this was becoming all too real to me, despite the surreal environment.

In this sea of people, all looking for someone, I searched for John-David. After about 20 minutes I found him. As I walked towards him, I almost laughed inside. This was, in part, a sign of my relief at finding him alive and unhurt, but also because members of the media were encircling him, leaving his face all but hidden by a sea of microphones. He was telling stories that he’d tell again and again, as the media remained fixated on telling the Santana story.

Little did John-David or I know that his life was about to change in ways we couldn’t have imagined. But during the next week, it felt as though we were riding a roller coaster as John-David became a voice to which many in the media turned for storytelling and comment. As his parent, I wanted to let him handle this situation in ways that felt right to him, but I also felt protective.

At times, the tug-and-pull of the media was unnerving: It seemed every reporter wanted a piece of John-David, and they wouldn’t leave him alone. Our phone rang at all hours of the day and night, and everyone expected him to respond to them immediately. There were times when all of this became frightening for me and for John-David. He handled it well and remained respectful to all, but at times I was worried that the media had taken control. Or so it seemed.

Upon returning home from school that day, we were confronted at our front door by a newspaper reporter. I found that extremely scary, and I began to understand how relentless members of the media were going to be in getting their story. I remember this woman from CBS’s morning show. She followed us—literally stalked us—throughout the entire day while John-David did interviews. She wanted an “exclusive,” she said, and was rude and pushy in her approach. Another woman with CNN’s “Larry King Live” tried to entice us with an offer of another exclusive. She went as far as getting Larry King on the phone to talk with us.

It became apparent to me I had to regain as much control as I could. An exclusive was given to “Good Morning America,” and John-David agreed to appear on “Nightline.” We decided to do these particular interviews because of how we were approached; I did not feel threatened by the people who spoke with us from these programs and appreciated the ways in which they went about gaining our confidence and their willingness to tell the story correctly. In fact, after we had agreed to do the ABC morning show, they provided us with a person who “ran defense” for us; if someone from another network approached, our “defense person” told them we were doing their show and that was that. Having this person to help us was a big relief. With “Nightline,” the producer kept his distance, provided us time to think about what we wanted to do, and didn’t follow us around all day. Those personal qualities were what convinced John-David to go on that show.

John-David also did several local broadcasts on TV and radio and also on radio stations in San Francisco and Los Angeles. We received numerous calls from news media outside of California. Our voice mail stopped taking new messages on that first day once it reached 35 messages. They were all calls from members of the media. John-David received requests to be interviewed for several articles: The New York Times, USA Weekend magazine, and Upfront (a magazine geared for teens). He was invited to appear on “Politically Incorrect” with Bill Maher.

To be caught in this media frenzy could be overwhelming for anyone. I knew my son had reached a burnout point when he began declining interviews. At one point, in fact in an interview he did with The New York Times, John-David said, “I’m sick of myself.” To me, he confided, “I just don’t want to give another interview. I’m done for a while.”

At that point, members of the media, for the most part, respected his wishes and left him alone. The respect shown by most in the media to this decision sent an important signal to us; having already discovered the sometimes heartless nature of the beast, John-David now had a chance to see another side, a more compassionate one. This is perhaps one reason that the experience, in the end, served to interest John-David in possibly working in the media one day.

Many students and parents successfully avoided the blitz of the media. Some parents chose to keep their children totally away from contact with the media, but this was not possible for us after John-David did the initial interviews at the school. It had been his decision in those early moments to speak with the press, and he was, in my view, doing a good job in trying to respond to their questions. Every student on campus that day had a story to tell, as did every parent. Each story offered a unique perspective, but I understand that some did not want to get involved in telling and retelling what had happened.

I remember thinking that morning when I arrived at the school that everyone standing there was fair game for the media. Every time I looked up, I saw reporters talking with students or parents or bystanders, then moving on as they “targeted” the next person to talk with. As they approached, that person had the right to talk or not talk, but not talking to the media got harder and harder to do as more reporters arrived, each seeking sources of information. My sense at the time was that if people remained at the scene, they were fair game for the media. If they didn’t want to be hounded by the media, then my feeling was they should go home and stay away from the school.

For John-David, much that is positive emerged from the tragedy at his school. His experience in coping with what happened, and in working with the media, has made him grow in many ways. He is still taking pictures, freelancing for a newspaper, and will begin an internship with a local TV station in San Diego. He graduates from high school next year and begins another journey in his life. But I know he will carry with him forever that March morning and how it changed his life. I know I will.

Barbara Schardt works in hospital administration for a major HMO and is the mother of John-David, who attends Santana High, where he will be a senior this fall.