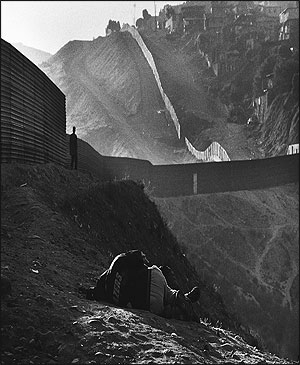

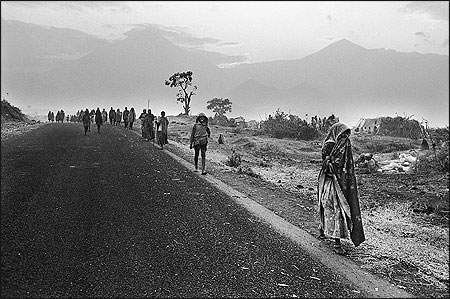

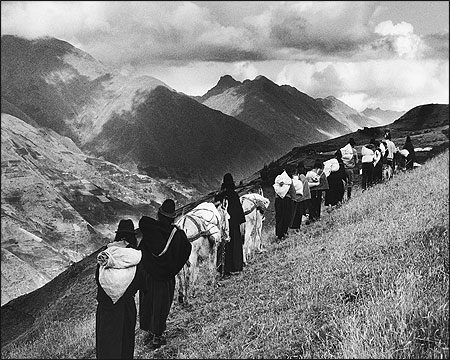

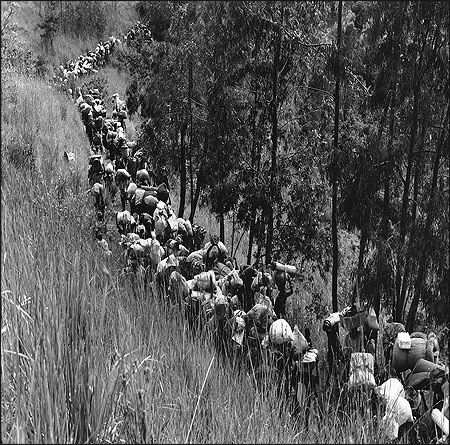

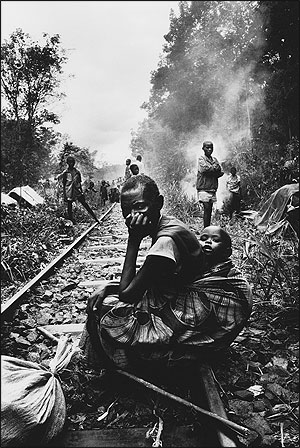

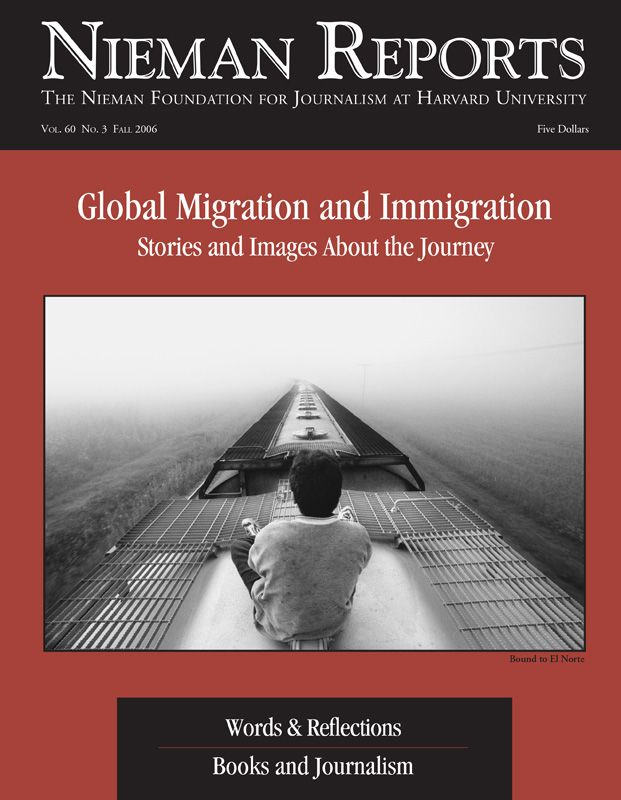

Sebastião Salgado went to 40 countries in six years to be among the world’s migrants and refugees so that he could tell visual stories of their difficult journeys as they leave their homes for places and lives unknown to them. "Many were going through the worst periods of their lives," he writes in the introduction of this collection of photographs entitled, "Migrations," published in 2000. "They were frightened, uncomfortable and humiliated. Yet they allowed themselves to be photographed, I believe, because they wanted their plight to be made known. When I could, I explained to them that this was my purpose. Many just stood before my camera and addressed it as they might a microphone." What follows are excerpts from Salgado’s introductory words and then several photographs from this collection.

The experience changed me profoundly. When I began this project, I was fairly used to working in difficult situations. I felt my political beliefs offered answers to many problems. I truly believed that humanity was evolving in a positive direction. I was unprepared for what followed. What I learned about human nature and the world we live in made me deeply apprehensive about the future.

True, there were many heartening occasions. I encountered dignity, compassion and hope in situations where one would have expected anger and bitterness. I met people who had lost everything but were still willing to trust a stranger. I came to feel the greatest admiration for people who risked everything, including their lives, to improve their destiny. I found it astonishing how human beings can adapt to the direst circumstances.

Yet if survival is our strongest instinct, all too often I found it expressed as hate, violence and greed. The massacres I saw in Africa and Latin America and the ethnic cleansing in Europe left me wondering whether humans will ever tame their darkest instincts.

I also came to understand, as never before, how everything that happens on earth is connected. We are all affected by the widening gap between rich and poor, by the availability of information, by population growth in the Third World, by the mechanization of agriculture, by rampant urbanization, by destruction of the environment, by nationalistic, ethnic and religious bigotry. The people wrenched from their homes are simply the most visible victims of a global convulsion entirely of our own making.

n that sense, "Migrations" also tells a story of our times. Its photographs capture tragic, dramatic and heroic moments in individual lives. Taken together, they form a troubling image of our world at the turn of the millennium.

People have always migrated, but something different is happening now. For me, this worldwide population upheaval represents a change of historic significance. We are undergoing a revolution in the way we live, produce, communicate and travel. Most of the world’s inhabitants are now urban. We have become one world: In distant corners of the globe, people are being displaced for essentially the same reasons.In Latin America, Africa and Asia, rural poverty has prompted hundreds of millions of peasants to abandon the countryside. And they crowd into gargantuan, barely inhabitable cities that also have much in common. Entire populations have moved for political reasons as well. Millions have fled Communist regimes. The collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe then freed many more to seek out new lives. Now, with the imposition of a new world political order, ethnic and religious conflicts are spawning armies of refugees and displaced persons. Many of these are becoming urbanized by the very experience of living in refugee camps. …

Everywhere I have traveled, the impact of the information revolution could be felt. Barely a half-century ago, the world could say it "did not know" about the Holocaust. Today, information — or at least the illusion of information — is available to everyone. Yet the consequences of "knowing" are not always predictable. Television informed the world of the massacres in Rwanda or the mass expulsions of Bosnians, Serbs and Kosovars almost as they were taking place, but these horrors nonetheless continued. On the other hand, North Africans can watch French television, Mexicans can watch American television, Albanians can watch Italian television, and Vietnamese can watch CNN or the BBC. The demonstration of conspicuous consumption is such that they can hardly be faulted for dreaming of migration. …

Today, information — or at least the illusion of information — is available to everyone. Yet the consequences of "knowing" are not always predictable.

Refugees and displaced persons, unlike migrants, are not dreaming of different lives. They are usually ordinary people — "innocent civilians" in the language of diplomats — going about their lives as farmers or students or housewives until their fates are violently altered by repression or war. Suddenly, along with losing their homes, jobs and perhaps even some loved ones, they are stripped even of their identity. They become people on the run, faces on television footage or in photographs, numbers in refugee camps, long lines awaiting food handouts. It is a cruel contract: In exchange for survival, they must surrender their dignity.

They are also rarely able to put their lives together again, or at least not as before. Some become permanent refugees, permanent camp-dwellers, like the Palestinians in Lebanon. Their lives acquire a certain stability but, as victims of politics, they remain vulnerable to politics. Some can go home, but choose not to, having built alternative lives that offer more security. Others who do eventually return to their countries have become different people, perhaps more politicized, certainly more urbanized.

But no matter what their final destiny is, all are forced to live with what they have learned about human nature. They have seen friends and relatives tortured, murdered or "disappeared," they have cowered in basements as their towns have been shelled, they have seen their homes burned to the ground. I would watch children laughing and playing soccer in refugee camps and wonder what hidden wounds they carried inside them. All too often, refugees have little to say in the political, ethnic or religious conflicts that degrade into atrocities. How can they be consoled when they have seen humanity at its worst? …

It could be said that the photographs in this book show only the dark side of humanity. But some points of light can be spotted in the global gloom. For example, humanitarian agencies are able to work among destitute refugees and migrants around the world thanks to the contributions of ordinary people. It could also be argued that Western public opinion spurred NATO interventions in Bosnia and Kosovo because of the emotional impact of television pictures of burning villages and massacre sites. And yet in Rwanda, the West saw the killings and did nothing to stop them. Today, good and evil are inseparable because we know about both.

But is it enough simply to be informed? Are we condemned to be largely spectators? Can we affect the course of events?

People flee wars to escape death, they migrate to improve their fortunes, they build new lives on foreign lands, they adapt to extreme hardship. Everywhere, the individual survival instinct rules. Yet as a race, we seem bent on self-destruction.

I have no answers, but I believe that some answers must exist, that humanity is capable of understanding, even controlling, the political, economic and social forces that we have set loose across the globe. Can we claim "compassion fatigue" when we show no sign of consumption fatigue? Are we to do nothing in face of the steady deterioration of our habitat, whether in cities or in nature? Are we to remain indifferent as the values of rich and poor countries alike deepen the divisions of our societies? We cannot.

My hope is that, as individuals, as groups, as societies, we can pause and reflect on the human condition at the turn of the millennium. The dominant ideologies of the 20th century — communism and capitalism — have largely failed us. Globalization is presented to us as a reality, but not as a solution. Even freedom cannot alone address our problems without being tempered by responsibility, order, awareness. In its rawest form, individualism remains a prescription for catastrophe. We have to create a new regimen of coexistence.

More than ever, I feel that the human race is one. There are differences of color, language, culture and opportunities, but people’s feelings and reactions are alike. People flee wars to escape death, they migrate to improve their fortunes, they build new lives on foreign lands, they adapt to extreme hardship. Everywhere, the individual survival instinct rules. Yet as a race, we seem bent on self-destruction.

Perhaps that is where our reflection should begin: that our survival is threatened. The new millennium is only a date in the calendar of one of the great religions, but it can serve as the occasion for taking stock. We hold the key to humanity’s future, but for that we must understand the present. These photographs show part of this present. We cannot afford to look away.

Humanity’s Journey