Their psychiatric files, their poems, pictures and diaries sat in piles by my bed. I read them before I slept. I dreamed about them at night. I thought of them during the day. They were children with psychiatric troubles, children whose lives were interrupted by illnesses that left them suicidal, lonely and sometimes raging. For eight months, their faces, their words lived in my head, and the papers that chronicled their mental illnesses filled my home.

Telling their story was one of the most complicated and darkest assignments I’ve ever written in my 22-year career. And it was one of the most important. These children were all but invisible. Few people in Maine knew that more than 400 of these kids ended up in emergency rooms each month, screaming, raging, begging for help. Few knew that hundreds more of these children languished in juvenile lockup or were sent out of state for psychiatric treatment because Maine had nothing to offer them.

Unless there was a scandal or lawsuit, the plight of these kids never made headlines. Doctors and social workers had told me the lack of care for Maine’s mentally ill children was the biggest crisis the state faced. But they also said I’d never be able to tell the story. They said I’d never persuade parents to talk because of the stigma and secrecy that surround mentally ill children. They told me I’d never get state records on how often Maine shipped kids away for care, how much the out-of-state treatment cost, or how many children grew worse because they didn’t receive proper psychiatric help.

I knew there would be many obstacles to telling this story, and the confidentiality that blanketed these children would be one of the biggest. But I also knew these kids deserved to have their stories told. Without help, many of them faced bleak futures. They’d be kicked out of their schools, their homes, and their communities. They’d be sent far from Maine to psychiatric hospitals and facilities around the country with no loved ones to be near them or look after them.

Joey Tracy spent much of the 11 months he was locked up at the juvenile detention center crying. Another boy detained at the center drew this sketch of Joey with a tear running down his face. Used by permission of Susan Tracy.

Reporting on Mental Health

My newspaper, the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, a small 75,000 circulation daily, agreed that Maine’s failure to help these children was an important story to tell. I figured it’d take me three or four months to get it into the paper. It took double my prediction—eight months.

During those months of reporting and writing, the story simmered always in my thoughts. When I biked or ran, I did not see the ocean, the pine trees or sky. In my mind’s eye, I was seeing and thinking about the children I visited in juvenile lockups, courtrooms or psychiatric hospitals. I know I celebrated my daughters’ birthdays, Christmas and the Fourth of July, but those celebrations are hazy memories clouded by a story that consumed me and, at times, left me with a lingering sadness.

I began my reporting in December 2001. It took me the first two months to just try to figure out the state’s complicated mental health care system for kids. Several more months were exhausted by hundreds of interviews, some just to get the names and phone numbers of families with mentally ill children. I begged and cajoled doctors, psychiatrists and social workers to contact parents who might be willing to talk about their child’s unmet psychiatric needs. Several of them bristled at my request, concerned about confidentiality and their fragile patients.

“Parents feel blamed for their kids’ illnesses,” some told me. “They’re too ashamed to talk about it.” Thankfully, several doctors and social workers believed the story needed to be told and risked their relationship with families by calling them for me. In the dead of winter, I began phoning parents myself. Talking with them was exhausting. Initial calls lasted an hour and sometimes two. The stories about their children were complicated and painful. Many of these parents spoke fast. They were accustomed to telling their stories over and over to people who cut their conversations short or hung up on them. Several of the parents I spoke with cried, cursed and shouted as they told me about their child’s illness and how they could not find help in Maine. They also thanked me for listening and for caring.

Many of these families couldn’t talk during the day because they worked or were too busy taking care of their kids. I interviewed them nights, weekends, on Mother’s Day, and Memorial Day. Mothers called me at home when their children smashed windows, screamed for hours, grabbed knives, or slipped into severe depression. They called me when police arrested their kids or rushed them to the emergency room.

I visited families in their homes, sat with them in kitchens, and hung out with children in their bedrooms. I flipped through their scrapbooks and photo albums, and they loaned me boxes of their psychiatric files, their diaries, letters and poems. Stacks of their records covered my night table, bureaus, bookshelves and kitchen counters.

Documents and Databases and Real Lives

The deeper I dug, the more the story grew. By the end of my reporting, I’d spoken with more than 500 doctors, social workers, family members and mental health experts, and I had reviewed more than 4,000 pages of psychiatric reports, state and national records. One bleak February afternoon, I received a database detailing how many Maine kids had been sent out of state for psychiatric care from 1997 through 2001. It listed how long the children were gone, where they were sent, and whether they were in state or parental custody. This database was 15-pages-long and included information about 737 kids. Many of these children had been sent away for two, three and four years.

I remember staring at that list for hours that day. Questions came to my mind. Who were these kids? Why were they gone for so long? Did anybody care about them? Were they worse or better after being away from their homes for so long? I shared these statistics with New Eng-land and national mental health experts, and many of them were stunned. A few told me, “Wow. That’s a lot of kids sent away for such a small state.” Whenever I grew exasperated with the story, the painful and endless interviews, the frequent calls to my home, I stared at that list. And I stared at the pictures of the children I wrote about. They were kids like my own, but they were also kids who needed help.

I stared often at a sketch of Joey Tracy. Joey began hearing voices when he was 11. Doctors diagnosed him with severe depression, conduct disorder, and possibly psychosis. By the time he was 15, Joey had been in and out of several psychiatric hospitals and programs. He landed in the juvenile lockup for burglary, harassing his teachers and classmates, and trying to kill himself with a homemade bomb. While he was locked away, he tried to drown himself in the toilet. He sliced his wrists with paper clips and staples. He jumped off a 20-foot tier.

Desperate for help, Joey’s mom gave up custody of her son to the state so that he could get the care she couldn’t afford to give him. Maine social workers told her if Joey was a state ward, he’d receive more federal money to pay for a group home, and there he’d receive counseling.

But the federal money didn’t matter. There still was no place for Joey in Maine. He languished in the juvenile detention center, waiting for treatment. The state made plans to send Joey to Pennsylvania or Georgia. Joey made plans to kill himself. He had never been on a plane before and dreaded being sent so far from home. Joey wrote long letters to his mother, telling her he missed and loved her. He also drew a gravestone with his name on it. Joey cried daily during the 11 months he waited for help. Another kid at the lockup drew a sketch of Joey, a tear falling from his eye. Joey’s mom sent the drawing to me, and we published it with his story.

Tammy Jackson was one of the mothers I talked with weekly and often daily. Tammy and two of her three teenage daughters each lived with bipolar disorder. The illness provoked sudden and uncontrollable mood swings. Tammy’s eldest daughter, Emily, was 15 and had been rushed to the emergency room more than a dozen times in two years.

Emily tossed bowls, TV remotes, stereos. She smashed windows, screamed for hours, slapped and swore at her sisters, and she cried at night, sobbing, unable to sleep.

Police came to the Jackson home weekly, sometimes daily, to help calm Emily. They arrested Emily for assaulting her father. They also arrested her father for restraining Emily too roughly. A police officer told Tammy, “Your daughter is an animal.” After he left the house, Tammy ran to the bathroom and threw up.

Tammy shared her journal with me. The blue binder held several hundred pages of notebook paper, thoughts she scribbled daily. She wrote about her anger, her pain, her shame for “Hating Emily’s illness. Hating Emily’s actions. Hating our life.” Tammy’s youngest daughter, Stephanie, dreamt of being normal. She talked about going to the psychiatric ward when the “hurt got really bad.” And she talked about the loneliness. At night, the 13-year-old hugged Abigail, a plastic doll the size of an infant. “Dolls are my friends,” she told me, squeezing Abigail. “Sometimes, they’re the only friends I have.”

The image of Stephanie clutching her doll haunted me. I thought of her as she went in and out of the psychiatric ward during the months when I was reporting this story. A few days before the series was to be published, Stephanie was placed back in the hospital. She had tried to kill herself.

We had planned to use her photograph and story on the front page, and I worried about how it would affect her. I asked her mom what she thought, and she agreed to talk it over with Stephanie. They both felt strongly that their story needed to be told. Once the series was published, distant family, friends, church members offered comfort, support to the family.

“No one understood what hell our lives were like,” Tammy told me.

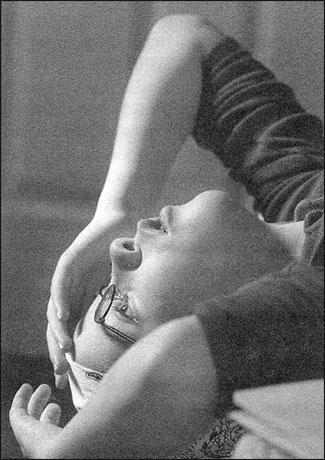

Tammy Jackson’s oldest daughter Emily, 15, suffers with bipolar mental illness and sometimes rages out of control, bringing the police to their Lewiston home. Photo by John Ewing/Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

Stephanie Jackson, 13, hangs her head off the side of her bed while talking with her twin sister, Bethany. Stephanie was born into a family that has struggled with mental illness for generations. Photo by John Ewing/Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

Reaction to the Stories

The Jackson’s story appeared in the newspaper in August 2002 as part of a three-day series, “Castaway Children: Maine’s Most Vulnerable Kids.” The stories chronicled the lives of several mentally ill children and their families. The series also looked at how Maine spent the bulk of its money on treating kids in crisis instead of preventing them from growing sicker.

The stories provoked outrage and change. The newspaper received 250 calls, e-mails and letters from readers, demanding Maine provide better care for its most vulnerable kids. John Baldacci, newly elected governor, promised to rebuild the state’s mental health care system for kids. Susan Collins, U.S. senator from Maine, asked the U.S. Inspector General to investigate why families in Maine and other states have to give up custody of their children to receive proper psychiatric treatment. Public marches and legislative hearings were held. Most importantly, these children were no longer invisible. Family, friends, politicians listen to their stories now.

I remain in touch with many of the families I wrote about. The Jacksons sent me a Christmas card and a portrait of their family. They still struggle with their illnesses. Emily and Stephanie are receiving help in group homes now.

After the series was published, it took me months to clear the psychiatric files and records from my home. But I kept the Jackson family portrait. It is a reminder to me that tough stories, especially stories about children, are worth the long hours, lost sleep, and inevitable obsession.

Barbara Walsh writes about children for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram. She was part of The Lawrence (Mass.) Eagle-Tribune reporting team that won a Pulitzer in the General News Reporting category in 1988. “Castaway Children” can be found at: pressherald.mainetoday.com/news/children/castawaychildren.shtml.