This article is adapted, in part, from an essay Gillmor wrote in 2008 as part of the Media Re:public project at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. In the Winter 2008 Nieman Reports, Persephone Miel, who directed that project, wrote “Media Re:public: My Year in the Church of the Web.”

In the age of democratized media, the tools of creation are increasingly in everyone’s hands. The personal computer that I’m using to write this essay comes equipped with media creation and editing tools of such depth that I can’t begin to learn all their capabilities. One of the devices I use regularly boasts video recording and playback, still-camera mode, audio recording, text messaging, and GPS location, among other tools that make it a powerful media creation device (and, by the way, it’s a phone).

Equally important in this world of democratized media, we can make what we create widely accessible. With traditional media, we produced something, usually manufactured, and then distributed it—put it in trucks or broadcast it to receivers in a one-to-many mode. Today, we create media and post it online. We make it available; people come and get it. There’s an element of distribution here, by virtue of letting people know it’s there, but the essential fact in a one-to-one or many-to-many world is availability.

This democratization gives people who have been mere consumers the ability to be creators. With few exceptions, we are all becoming the latter as well as the former, though to varying degrees. More exciting, some creators become collaborators.

What does this mean? For one thing, contrary to the panic we’re hearing from newspaper people whose jobs are disappearing, the end of our oligopolistic system of media and journalism is good news, not something to dread. Indeed, I no longer worry about a sufficient supply of journalism, not in the emerging age of abundance. We’ll have ample amounts of information and journalism—in some ways, too ample.

Why, given the crumbling of newspapers and the news industry in general, should we believe in abundance? Just look around. The number of experiments taking place in new media is stunning and heartening. Entrepreneurs are moving swiftly to become pioneers in tomorrow’s news. Philanthropic enterprises are filling gaps they perceive in coverage. Even the traditional media dinosaurs are, probably too late, moving to adapt to the changes that have put them in such difficulty, namely the transition from monopoly and oligopoly to a truly competitive marketplace.

Most of the experiments in new journalism and business models will fail. That is the nature of the new and of start-up cultures. But even a small percentage of successes will still be a large number because so many people are trying. We won’t lack for supply, though we should never stop trying to make it better.

But to ensure that this supply of information is useful and trustworthy, we’ll have to rethink our relationship with media. In the supply and demand system that guides all marketplaces, including the marketplace of ideas and information, we need better demand, not just more supply. To ensure that demand, we’ll need to transform ourselves from passive consumers of media into active users. And to accomplish that, we’ll have to instill throughout our society principles that add up to critical thinking and honorable behavior.

Even those of us who are creating a variety of media are still—and always will be—more consumers than creators. For all of us in this category, the principles (illuminated below) come mostly from common sense. Call them skepticism, judgment, understanding and reporting.

Media saturation requires us to become more active as consumers, in part to manage the flood of data pouring over us each day but also to make informed judgments about the significance of what we do see. And when we create media that serves a public interest or journalistic role, we need to understand what it means to be journalistic, as well as how we can help make it better and more useful. This adds up to a new kind of media literacy, based on key principles for both consumers and creators. These categories will overlap to some degree—as do their principles, each of which requires an active, not passive, approach to media.

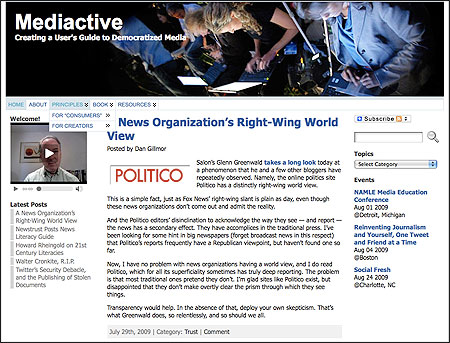

The Mediactive project consists of a book, Web site, and more with the goal of creating a user’s guide to democratized media and persuading people who have been passive consumers to become active users.

Active Media Users, Not ‘Consumers’

Be skeptical of absolutely everything. We can never take entirely for granted the absolute trustworthiness of what we read, see, hear and use. This is the case for information from traditional news organizations, blogs, online videos, and every other form known now or yet to be invented.

Although skepticism is essential, don’t be equally skeptical of everything. We all have an internal “trust meter” of sorts, largely based on education and experience. We need to bring to digital media a more rigorous level of parsing, adapted from but going far beyond what we learned in a less complex time when there were only a few primary sources of information. A key point: Some things deserve negative credibility; that is, they would need to improve just to achieve zero credibility.

Go outside your personal comfort zone. The “echo chamber” effect—our tendency as human beings to seek information that we’re likely to agree with—is well known. To be well informed, we need to seek out and pay attention to sources of information that will offer new perspectives and challenge our assumptions. This is easier than ever before, due to the enormous amount of news and analysis available on the Internet. If we’re not relentless with ourselves, we can’t expect much of others.

Ask more questions. This principle goes by many names: research, reporting, homework and many others. The more personal or important you consider the topic at hand, the more essential it becomes to follow up on the media that cover the topic. Lifelong learning is now accepted as fundamental, and it applies to our use of media, too.

Understand and learn media techniques. In a media-saturated society, we need to know how digital media work. The techniques of media creation are becoming second nature, at least to younger people. But it’s equally essential to understand the ways people use media to persuade and manipulate. Moreover, we need to help each other know who’s doing the manipulating.

Media Creation, When Credibility Matters

Do your homework and then do some more. You can’t know everything, but good reporters try to learn as much as they can about a topic. It’s better to know much more than you publish than to leave big holes in your story. The best reporters always want to make one more call, check with one more source, because they worry that the fact(s) they don’t know are the ones that might matter the most.

Get it right, every time. Accuracy is the starting point for all solid journalism. Get your facts right, then check them again. Factual errors, especially ones that are easily avoidable, do more to undermine trust than almost any other failing.

Be fair to everyone. Whether you are trying to explain something from a neutral point of view or arguing from a specific side, fairness counts. You can’t be perfectly fair, and people will see what you’ve said from their own perspectives, but making the effort is more than worth the difficulty. Like all of these principles, fairness is a never-ending process, not an outcome.

Think independently, especially of your own biases. Being independent can mean many things, but independence of thought may be most important. Creators of media, not just consumers, need to venture beyond their personal comfort zones.

Practice and demand transparency. This is essential not just for citizen journalists and other new media creators but also for those in traditional media. The kind and extent of transparency may differ. For example, bloggers should reveal biases. Meanwhile, traditional journalists may have pledged individually not to have conflicts of interest, but that doesn’t mean they are unbiased. They should help their audiences understand what they do, and why, in the course of their journalism.

Who should teach or coach these principles? Parents and schools, of course, should lead. It’s tragic, however, that journalism organizations haven’t made this one of their core missions over the years; had they done so they might not be in as much trouble because they would have helped people understand better what it takes, from all of us, to have the kind of news and information we need.

These principles are just the beginning of a larger conversation. In my new project called “Mediactive”—which includes a book I am writing, a Web site (mediactive.com) and more—I intend to explore ways to help foster a new generation of activist media users and better journalism in general. Most of all, what I hope to contribute to is a society in which critical thinking is understood as not just an interesting concept but an essential part of our daily lives.

Dan Gillmor is director of the Knight Center for Digital Media Entrepreneurship at Arizona State University’s Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communication. He is author of “We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People,” published by O’Reilly Media in 2004.

In the age of democratized media, the tools of creation are increasingly in everyone’s hands. The personal computer that I’m using to write this essay comes equipped with media creation and editing tools of such depth that I can’t begin to learn all their capabilities. One of the devices I use regularly boasts video recording and playback, still-camera mode, audio recording, text messaging, and GPS location, among other tools that make it a powerful media creation device (and, by the way, it’s a phone).

Equally important in this world of democratized media, we can make what we create widely accessible. With traditional media, we produced something, usually manufactured, and then distributed it—put it in trucks or broadcast it to receivers in a one-to-many mode. Today, we create media and post it online. We make it available; people come and get it. There’s an element of distribution here, by virtue of letting people know it’s there, but the essential fact in a one-to-one or many-to-many world is availability.

This democratization gives people who have been mere consumers the ability to be creators. With few exceptions, we are all becoming the latter as well as the former, though to varying degrees. More exciting, some creators become collaborators.

What does this mean? For one thing, contrary to the panic we’re hearing from newspaper people whose jobs are disappearing, the end of our oligopolistic system of media and journalism is good news, not something to dread. Indeed, I no longer worry about a sufficient supply of journalism, not in the emerging age of abundance. We’ll have ample amounts of information and journalism—in some ways, too ample.

Why, given the crumbling of newspapers and the news industry in general, should we believe in abundance? Just look around. The number of experiments taking place in new media is stunning and heartening. Entrepreneurs are moving swiftly to become pioneers in tomorrow’s news. Philanthropic enterprises are filling gaps they perceive in coverage. Even the traditional media dinosaurs are, probably too late, moving to adapt to the changes that have put them in such difficulty, namely the transition from monopoly and oligopoly to a truly competitive marketplace.

Most of the experiments in new journalism and business models will fail. That is the nature of the new and of start-up cultures. But even a small percentage of successes will still be a large number because so many people are trying. We won’t lack for supply, though we should never stop trying to make it better.

But to ensure that this supply of information is useful and trustworthy, we’ll have to rethink our relationship with media. In the supply and demand system that guides all marketplaces, including the marketplace of ideas and information, we need better demand, not just more supply. To ensure that demand, we’ll need to transform ourselves from passive consumers of media into active users. And to accomplish that, we’ll have to instill throughout our society principles that add up to critical thinking and honorable behavior.

Even those of us who are creating a variety of media are still—and always will be—more consumers than creators. For all of us in this category, the principles (illuminated below) come mostly from common sense. Call them skepticism, judgment, understanding and reporting.

Media saturation requires us to become more active as consumers, in part to manage the flood of data pouring over us each day but also to make informed judgments about the significance of what we do see. And when we create media that serves a public interest or journalistic role, we need to understand what it means to be journalistic, as well as how we can help make it better and more useful. This adds up to a new kind of media literacy, based on key principles for both consumers and creators. These categories will overlap to some degree—as do their principles, each of which requires an active, not passive, approach to media.

The Mediactive project consists of a book, Web site, and more with the goal of creating a user’s guide to democratized media and persuading people who have been passive consumers to become active users.

Active Media Users, Not ‘Consumers’

Be skeptical of absolutely everything. We can never take entirely for granted the absolute trustworthiness of what we read, see, hear and use. This is the case for information from traditional news organizations, blogs, online videos, and every other form known now or yet to be invented.

Although skepticism is essential, don’t be equally skeptical of everything. We all have an internal “trust meter” of sorts, largely based on education and experience. We need to bring to digital media a more rigorous level of parsing, adapted from but going far beyond what we learned in a less complex time when there were only a few primary sources of information. A key point: Some things deserve negative credibility; that is, they would need to improve just to achieve zero credibility.

Go outside your personal comfort zone. The “echo chamber” effect—our tendency as human beings to seek information that we’re likely to agree with—is well known. To be well informed, we need to seek out and pay attention to sources of information that will offer new perspectives and challenge our assumptions. This is easier than ever before, due to the enormous amount of news and analysis available on the Internet. If we’re not relentless with ourselves, we can’t expect much of others.

Ask more questions. This principle goes by many names: research, reporting, homework and many others. The more personal or important you consider the topic at hand, the more essential it becomes to follow up on the media that cover the topic. Lifelong learning is now accepted as fundamental, and it applies to our use of media, too.

Understand and learn media techniques. In a media-saturated society, we need to know how digital media work. The techniques of media creation are becoming second nature, at least to younger people. But it’s equally essential to understand the ways people use media to persuade and manipulate. Moreover, we need to help each other know who’s doing the manipulating.

Media Creation, When Credibility Matters

Do your homework and then do some more. You can’t know everything, but good reporters try to learn as much as they can about a topic. It’s better to know much more than you publish than to leave big holes in your story. The best reporters always want to make one more call, check with one more source, because they worry that the fact(s) they don’t know are the ones that might matter the most.

Get it right, every time. Accuracy is the starting point for all solid journalism. Get your facts right, then check them again. Factual errors, especially ones that are easily avoidable, do more to undermine trust than almost any other failing.

Be fair to everyone. Whether you are trying to explain something from a neutral point of view or arguing from a specific side, fairness counts. You can’t be perfectly fair, and people will see what you’ve said from their own perspectives, but making the effort is more than worth the difficulty. Like all of these principles, fairness is a never-ending process, not an outcome.

Think independently, especially of your own biases. Being independent can mean many things, but independence of thought may be most important. Creators of media, not just consumers, need to venture beyond their personal comfort zones.

Practice and demand transparency. This is essential not just for citizen journalists and other new media creators but also for those in traditional media. The kind and extent of transparency may differ. For example, bloggers should reveal biases. Meanwhile, traditional journalists may have pledged individually not to have conflicts of interest, but that doesn’t mean they are unbiased. They should help their audiences understand what they do, and why, in the course of their journalism.

Who should teach or coach these principles? Parents and schools, of course, should lead. It’s tragic, however, that journalism organizations haven’t made this one of their core missions over the years; had they done so they might not be in as much trouble because they would have helped people understand better what it takes, from all of us, to have the kind of news and information we need.

These principles are just the beginning of a larger conversation. In my new project called “Mediactive”—which includes a book I am writing, a Web site (mediactive.com) and more—I intend to explore ways to help foster a new generation of activist media users and better journalism in general. Most of all, what I hope to contribute to is a society in which critical thinking is understood as not just an interesting concept but an essential part of our daily lives.

Dan Gillmor is director of the Knight Center for Digital Media Entrepreneurship at Arizona State University’s Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communication. He is author of “We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People,” published by O’Reilly Media in 2004.