I took my usual route to work one recent morning, thinking along the way that The Times-Picayune was closing in on 700 days of staying in business since Katrina’s floodwaters forever changed one of America’s great cities. It’s a milestone that few others took note of, and it seems a minor accomplishment for a newspaper that’s been around for 170 years. But it’s the way I think these days, living in a place where one searches for signs of hope a day at a time. After all, to have been here two years ago, when the levees broke and our readership was dispersed down interstates to anywhere dry, the thought occurred that we might not be here at all.

Yet in this disaster, we learned something about our readers: They didn’t leave us, they went to a safe place and found us — online — in staggering numbers, counting on us, like they always have, to tell them what was happening to their homes and neighborhoods. And we were there then, a ragtag bunch of volunteer journalists, on bicycles, in kayaks and canoes, wading in the water all over New Orleans, doing our best to gather the information and get it out.

My 10-minute drive to work is a daily demonstration of both what has happened to this city and what’s possible. It’s also epitomizes how I see the newspaper business as it sorts itself out in similar ways — forced, in some places out of desperation, to figure out what’s happening and what’s possible.

I live in Old Lakeview, just one of the neighborhoods that suffered massive flooding in a city where the devastation zone was seven times the size of Manhattan. I saw my home via kayak the day after the storm (swam through it, actually, in an illogical, ill-planned but ultimately successful mission to save the family dog). As I floated up to my house, I drifted on black water and cried. I thought it was over. Our home, our neighborhood, it didn’t seem a recovery would ever be possible. My daughter had evacuated. I remember thinking that I did not want her to see what had happened here.

We are living in that home today, on a block where recovery now seems not only possible, but also inevitable. My 75-year-old neighbor is back, having been diagnosed with cancer and undergone two surgeries while he was gone, but never losing his determination to come back home. There’s a young couple building a new home a few doors down. The local coffee shop on the corner is gone, but a Starbucks took its place. The locally owned pizza joint came back, doubling its pre-Katrina space.

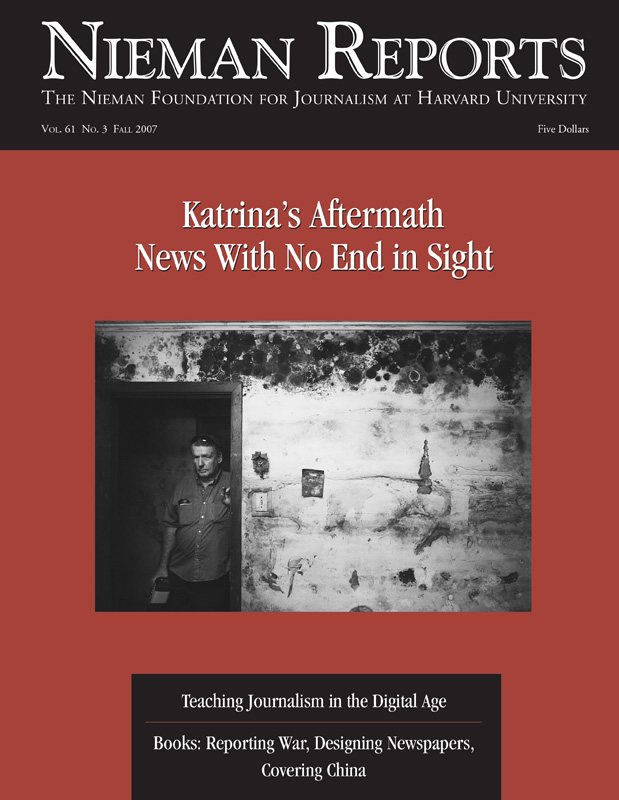

Driving out of my neighborhood, I see homes brought back to life right next door to residential ghosts, haunting walls stripped to studs that prop up tattered rooftops. But the picture of what this place is going to be gets a little clearer every day. I notice each change, the demolition crew surgically hauling off the misery, the beautiful sound of a carpenter’s hammer that tells me someone is going to live there. Crossing into Mid-City, which straddles the flood line, the recovery is more complete. A surprising cluster of restaurants have taken root on North Carrollton Avenue, some of them old favorites renovated and reopened, others new offerings making an investment of faith.

It is interesting, what is happening here. It is true that not everyone who used to live in New Orleans has come back. What is surprising, and certainly under the radar of the national press, is the number of people and businesses coming here who were not New Orleanians before Katrina. The city is learning that it doesn’t have to be exactly the same as it was to succeed. In many ways, specifically in the realms of public education and the criminal justice system, it will be a lot better off if it never reverts to what it was.

Overcoming the Fear of Change

All of this change going on around us offers a parallel lesson for print journalists, many of whom are shaken by the prospect of transforming their craft for an online audience. And while it’s not uncommon to hear talk in newsrooms of how it’s a good time to get out of the newspaper business, I’d argue that there never has been a more exciting time to be in it.

To figure out what’s holding us back, look no further than fear. Journalists encourage change in the world but don’t change themselves. We’re much more prone to pondering our fates with the same cynical energy we apply to just about everything we evaluate. It is somewhat amazing that journalists who, by and large, have great confidence in their individual talents hold such little faith in our ability to achieve collective success.

A change in attitude is needed, with a change in strategy close behind. If innovation and vision, versatility and wide-open creativity are seen as strengths — and if the opportunity to draw your newspaper closer than ever to your community is relished — then staying in the news business is a good place to be. And as we continue to figure out the changing role of newspapers in our communities, Katrina offers an undeniable truth: Our customers might not all want to consume the news in precisely the same way, but they all want the news. And more than any other entity, they trust their local newspaper to give them the information they want and need.

Thinking Local

Our Web site came of age during Katrina for a simple reason — it had to. Virtually all of the New Orleans area had evacuated for the hurricane, and the failed federal levees prevented hundreds of thousands of residents from coming back, some for several weeks. A Web site that averaged 800,000 page views per day pre-Katrina exploded to 30 million per day in the weeks after the storm. Even now, two years later, its daily audience is double what it was before the hurricane.

People signed on from wherever they were, devouring what we were reporting and adding information of their own in forums that sprang up almost instantly. They asked for help finding family members. They posted updates on what they knew about their neighborhoods, specific down to the block. Think about it. The newspaper became a true forum, not just in the stories we posted as quickly as we could, but also in those we collected from our readers.

We would be foolish to ever end that kind of reader engagement. Indeed, we saw it as the blessing that it is. Imagine a town square on every computer, where everyone can see what everyone else is saying, and they can all show up whenever they want. And it is the newspaper hosting a community discussion that never ends, while publishing its own information and welcoming what its readers have to contribute. It’s a relationship we’d never had before, but it’s one our readers craved. (We always told our readers it’s their newspaper, but how many newspapers really have lived up to that claim?)

Yet, even with the changes in how our news gets delivered, The Times-Picayune is not a completely different place than it was before the storm. It would have made no sense to start over. The paper’s penetration ranked first in the nation among major dailies long before Katrina, owed mainly to a sustained and substantial commitment to providing readers with a local newspaper — from the front page to the metro section and high-quality community news sections — tailored to the places they live. When our readers ask us for something, we strive to find a way to say yes, instead of an overintellectualized journalistic excuse to say no.

So when a newspaper announces a renewed commitment to local news, I always ask one question: Who is defining “local?” Is it the readers or the newsroom? To remain the primary source of news in your market, think hard about the answer.

As strange as this might sound, given what we’ve been through our newspaper is fortunate in many respects. The job we were doing before the flood was as important as what we did during the disaster in bringing our readership back quickly. Our print circulation went from 260,000 to zero in a day. To see it already back over 200,000 in a recovering market tells us we had a solid foundation. And that has allowed us to pursue our online goals from a starting point of success rather than panic. We also are privately held, benefiting from ownership that focuses on long-term goals instead of flavor-of-the-month fixes. We do not underestimate that advantage.

As our online work continues to expand, we are not losing sight of the philosophy that has driven our success. We want to be as local online as we are in the paper, and we intend to play to our primary strength — using the army of journalists we have working across the New Orleans area to gather local news and break it when we get it. From a murder to a mayoral press conference to a traffic-snarling car wreck at the corner of Magazine Street and Napoleon Avenue, we want it. Mainly, we want our readers to know if there’s any news agency in town most likely to be on the scene, their best bet is The Times-Picayune. And we want them to believe this whether they live in New Orleans or 40 miles away in Covington, on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

We want to keep it short, and we want it online quickly. We don’t want our reporters to labor over a finished product for tomorrow’s paper, we want whatever they can tell us in five minutes. If we get more details, we’ll update. To that end, we’ve made a fundamental change in how we equip our reporters. We are issuing laptops and wireless cards to every reporter on staff so that anyone can file a news update from anywhere at any time. It’s a learning process, but we’re not going to wait until we perfect it to launch it — it’s underway. Our journalists are already trained to do journalism; learning how to post to a blog page is as simple as sending an e-mail.

The Web and the Newsroom

There also are a couple of important things we’re not going to do. First and foremost, we’re not going to create a fancy Internet bureaucracy in the newsroom. The Times-Picayune has always taken a very lean approach to management. It’s one of the things that makes it a fun place to work. There is no Internet czar. There is no separate online staff, and we’re not going to create one just because it sounds great at a journalism convention. Quite frankly, we do not want to give all of our journalists a reason not to evolve: We’re going to evolve together. It will happen not because a guru demands it, but because self-preservation proves a powerful motivator.

This trend we’re seeing is not a fad; this is what we are becoming. Our business is changing, and we don’t want to look up in 10 years and be stuck with a bureaucracy we no longer need. So we’re skipping that step. Sure, we’re going to make some mistakes in the meantime, but we’ll learn from them. And as we tackle new endeavors, acquire new skills, and learn how to sell our journalism in every conceivable way, you know what else will happen? We’ll have some fun.

The other thing we’re not going to do is overthink the Internet. The endless intellectual wrangling that causes newspapers to move at a glacial pace should not preside over our online world. Stop worrying and get going, because nothing gets us there like getting started.

I think about that as I recall the frustration that came with rebuilding our house. I wanted to preserve its best features, its character, yet make it better than it was before. Things didn’t always go at the pace I wanted, people didn’t always do things how I wished they would. Sometimes it seemed like we weren’t ever going to get back home.

I learned the value of persistent patience, of knowing that I had to keep pushing to move the project a little more forward than it was yesterday. It was an incredible challenge but, one day, we had a brand-new house. Some parts of it are restored exactly like they were, others are gone forever. But the renovation was a success. This different house is a lot nicer and stronger than it used to be. I like to think our newspaper is, too.

David Meeks is city editor of The Times-Picayune in New Orleans. When the newspaper evacuated during massive flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Meeks, then the sports editor, remained in the city for six weeks and led a team of volunteers covering the story, working from makeshift news bureaus out of colleagues’ dry homes. He and his daughter, Juliet, moved back into their rebuilt home in March.

Yet in this disaster, we learned something about our readers: They didn’t leave us, they went to a safe place and found us — online — in staggering numbers, counting on us, like they always have, to tell them what was happening to their homes and neighborhoods. And we were there then, a ragtag bunch of volunteer journalists, on bicycles, in kayaks and canoes, wading in the water all over New Orleans, doing our best to gather the information and get it out.

My 10-minute drive to work is a daily demonstration of both what has happened to this city and what’s possible. It’s also epitomizes how I see the newspaper business as it sorts itself out in similar ways — forced, in some places out of desperation, to figure out what’s happening and what’s possible.

I live in Old Lakeview, just one of the neighborhoods that suffered massive flooding in a city where the devastation zone was seven times the size of Manhattan. I saw my home via kayak the day after the storm (swam through it, actually, in an illogical, ill-planned but ultimately successful mission to save the family dog). As I floated up to my house, I drifted on black water and cried. I thought it was over. Our home, our neighborhood, it didn’t seem a recovery would ever be possible. My daughter had evacuated. I remember thinking that I did not want her to see what had happened here.

We are living in that home today, on a block where recovery now seems not only possible, but also inevitable. My 75-year-old neighbor is back, having been diagnosed with cancer and undergone two surgeries while he was gone, but never losing his determination to come back home. There’s a young couple building a new home a few doors down. The local coffee shop on the corner is gone, but a Starbucks took its place. The locally owned pizza joint came back, doubling its pre-Katrina space.

Driving out of my neighborhood, I see homes brought back to life right next door to residential ghosts, haunting walls stripped to studs that prop up tattered rooftops. But the picture of what this place is going to be gets a little clearer every day. I notice each change, the demolition crew surgically hauling off the misery, the beautiful sound of a carpenter’s hammer that tells me someone is going to live there. Crossing into Mid-City, which straddles the flood line, the recovery is more complete. A surprising cluster of restaurants have taken root on North Carrollton Avenue, some of them old favorites renovated and reopened, others new offerings making an investment of faith.

It is interesting, what is happening here. It is true that not everyone who used to live in New Orleans has come back. What is surprising, and certainly under the radar of the national press, is the number of people and businesses coming here who were not New Orleanians before Katrina. The city is learning that it doesn’t have to be exactly the same as it was to succeed. In many ways, specifically in the realms of public education and the criminal justice system, it will be a lot better off if it never reverts to what it was.

Overcoming the Fear of Change

All of this change going on around us offers a parallel lesson for print journalists, many of whom are shaken by the prospect of transforming their craft for an online audience. And while it’s not uncommon to hear talk in newsrooms of how it’s a good time to get out of the newspaper business, I’d argue that there never has been a more exciting time to be in it.

To figure out what’s holding us back, look no further than fear. Journalists encourage change in the world but don’t change themselves. We’re much more prone to pondering our fates with the same cynical energy we apply to just about everything we evaluate. It is somewhat amazing that journalists who, by and large, have great confidence in their individual talents hold such little faith in our ability to achieve collective success.

A change in attitude is needed, with a change in strategy close behind. If innovation and vision, versatility and wide-open creativity are seen as strengths — and if the opportunity to draw your newspaper closer than ever to your community is relished — then staying in the news business is a good place to be. And as we continue to figure out the changing role of newspapers in our communities, Katrina offers an undeniable truth: Our customers might not all want to consume the news in precisely the same way, but they all want the news. And more than any other entity, they trust their local newspaper to give them the information they want and need.

Thinking Local

Our Web site came of age during Katrina for a simple reason — it had to. Virtually all of the New Orleans area had evacuated for the hurricane, and the failed federal levees prevented hundreds of thousands of residents from coming back, some for several weeks. A Web site that averaged 800,000 page views per day pre-Katrina exploded to 30 million per day in the weeks after the storm. Even now, two years later, its daily audience is double what it was before the hurricane.

People signed on from wherever they were, devouring what we were reporting and adding information of their own in forums that sprang up almost instantly. They asked for help finding family members. They posted updates on what they knew about their neighborhoods, specific down to the block. Think about it. The newspaper became a true forum, not just in the stories we posted as quickly as we could, but also in those we collected from our readers.

We would be foolish to ever end that kind of reader engagement. Indeed, we saw it as the blessing that it is. Imagine a town square on every computer, where everyone can see what everyone else is saying, and they can all show up whenever they want. And it is the newspaper hosting a community discussion that never ends, while publishing its own information and welcoming what its readers have to contribute. It’s a relationship we’d never had before, but it’s one our readers craved. (We always told our readers it’s their newspaper, but how many newspapers really have lived up to that claim?)

Yet, even with the changes in how our news gets delivered, The Times-Picayune is not a completely different place than it was before the storm. It would have made no sense to start over. The paper’s penetration ranked first in the nation among major dailies long before Katrina, owed mainly to a sustained and substantial commitment to providing readers with a local newspaper — from the front page to the metro section and high-quality community news sections — tailored to the places they live. When our readers ask us for something, we strive to find a way to say yes, instead of an overintellectualized journalistic excuse to say no.

So when a newspaper announces a renewed commitment to local news, I always ask one question: Who is defining “local?” Is it the readers or the newsroom? To remain the primary source of news in your market, think hard about the answer.

As strange as this might sound, given what we’ve been through our newspaper is fortunate in many respects. The job we were doing before the flood was as important as what we did during the disaster in bringing our readership back quickly. Our print circulation went from 260,000 to zero in a day. To see it already back over 200,000 in a recovering market tells us we had a solid foundation. And that has allowed us to pursue our online goals from a starting point of success rather than panic. We also are privately held, benefiting from ownership that focuses on long-term goals instead of flavor-of-the-month fixes. We do not underestimate that advantage.

As our online work continues to expand, we are not losing sight of the philosophy that has driven our success. We want to be as local online as we are in the paper, and we intend to play to our primary strength — using the army of journalists we have working across the New Orleans area to gather local news and break it when we get it. From a murder to a mayoral press conference to a traffic-snarling car wreck at the corner of Magazine Street and Napoleon Avenue, we want it. Mainly, we want our readers to know if there’s any news agency in town most likely to be on the scene, their best bet is The Times-Picayune. And we want them to believe this whether they live in New Orleans or 40 miles away in Covington, on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

We want to keep it short, and we want it online quickly. We don’t want our reporters to labor over a finished product for tomorrow’s paper, we want whatever they can tell us in five minutes. If we get more details, we’ll update. To that end, we’ve made a fundamental change in how we equip our reporters. We are issuing laptops and wireless cards to every reporter on staff so that anyone can file a news update from anywhere at any time. It’s a learning process, but we’re not going to wait until we perfect it to launch it — it’s underway. Our journalists are already trained to do journalism; learning how to post to a blog page is as simple as sending an e-mail.

The Web and the Newsroom

There also are a couple of important things we’re not going to do. First and foremost, we’re not going to create a fancy Internet bureaucracy in the newsroom. The Times-Picayune has always taken a very lean approach to management. It’s one of the things that makes it a fun place to work. There is no Internet czar. There is no separate online staff, and we’re not going to create one just because it sounds great at a journalism convention. Quite frankly, we do not want to give all of our journalists a reason not to evolve: We’re going to evolve together. It will happen not because a guru demands it, but because self-preservation proves a powerful motivator.

This trend we’re seeing is not a fad; this is what we are becoming. Our business is changing, and we don’t want to look up in 10 years and be stuck with a bureaucracy we no longer need. So we’re skipping that step. Sure, we’re going to make some mistakes in the meantime, but we’ll learn from them. And as we tackle new endeavors, acquire new skills, and learn how to sell our journalism in every conceivable way, you know what else will happen? We’ll have some fun.

The other thing we’re not going to do is overthink the Internet. The endless intellectual wrangling that causes newspapers to move at a glacial pace should not preside over our online world. Stop worrying and get going, because nothing gets us there like getting started.

I think about that as I recall the frustration that came with rebuilding our house. I wanted to preserve its best features, its character, yet make it better than it was before. Things didn’t always go at the pace I wanted, people didn’t always do things how I wished they would. Sometimes it seemed like we weren’t ever going to get back home.

I learned the value of persistent patience, of knowing that I had to keep pushing to move the project a little more forward than it was yesterday. It was an incredible challenge but, one day, we had a brand-new house. Some parts of it are restored exactly like they were, others are gone forever. But the renovation was a success. This different house is a lot nicer and stronger than it used to be. I like to think our newspaper is, too.

David Meeks is city editor of The Times-Picayune in New Orleans. When the newspaper evacuated during massive flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Meeks, then the sports editor, remained in the city for six weeks and led a team of volunteers covering the story, working from makeshift news bureaus out of colleagues’ dry homes. He and his daughter, Juliet, moved back into their rebuilt home in March.