There’s an entry into sports for everyone.

If you just want to stay top-layer casual, maybe check a score, or send a text to a relative when you see their favorite team won, you can do that. (What’s up, Unc! I see your Celtics made a nice deal!)

If you want to pretend to be a podcaster, a talking head, or a talk radio host, you can do that. (These are going to be the Top 5 Busts of the 2027 NBA Draft, and I’ll tell you why!)

If you want to follow sports the way people watch TV dramas, you can do that. (The Belichick-Brady Saga Continues!)

If you want to take the TMZ route, you’ll have as much fun going through the skeletons in athletes' lockers as you would celebrities’ closets. (Michael Jordan’s son is dating Scottie Pippen’s ex-wife!)

If you want to follow sports like it’s Wall Street, you can do that, too. (The Celtics are set to pay the highest luxury tax bill in league history!)

But of all the entry points, arguing always felt like the easiest way in. Didn’t matter if it was Jordan vs. LeBron or Top Five [insert anything you want here really] Of All Time, you could argue your way through the door.

As a sportswriter, it comes with the territory, but I got to a point where I didn’t feel like I was getting anything out of it. The conversations weren’t making me a better person. The arguments were usually reductive and binary. I didn’t know more about anything by debating draft flops, the greatest of all time, who needs a championship to cement their legacy, or if the 1996 Bulls could beat the 2017 Warriors.

I wanted to think about sports in a way that wasn’t combative, gossipy, or dramatic. I wanted to learn about sports, understand them better, and appreciate them more.

I didn’t want to argue who the greatest shooter was in basketball history. I wanted to know how shooting evolved from a novelty in 1979 (when the line was invented) to a genuine — if under-used — weapon within 20 years to a phenomenon by the 2000s to a skill that everyone must have if they play basketball in 2023.

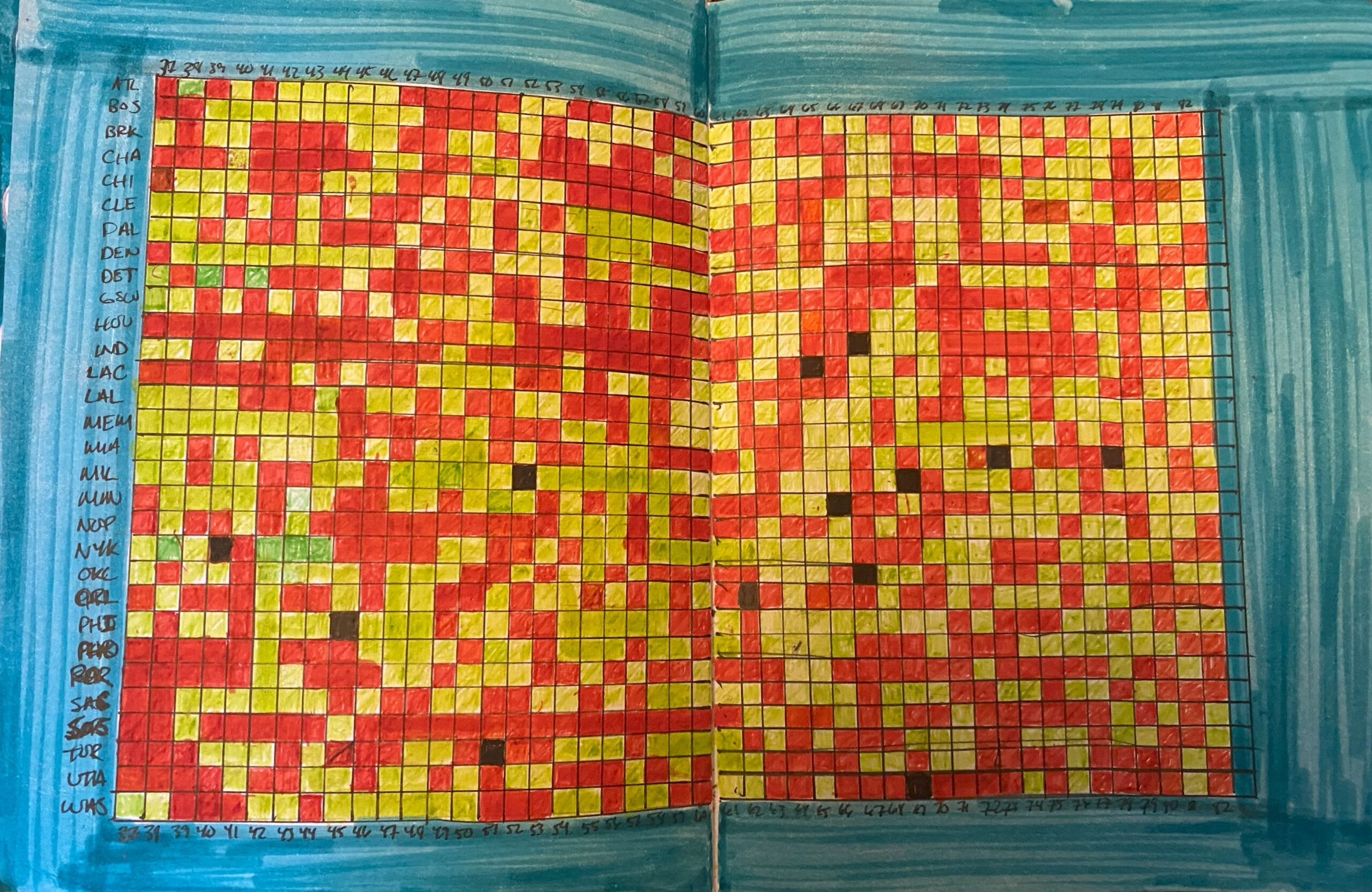

The best starting point I could come up with was a journal. If nothing else, it was a way to be mindful — a way to check in every day. It started with the basics — scores, standings, and so on — then it expanded into any interesting question that popped into my head. It started as chicken-scratch scribbles and turned into colorful doodles.

One example of this is dealing with predictions. They are a big part of sports reporting (something about being “experts”), but they were never my thing. But I found something that worked for me when the Celtics faced the Warriors in the NBA Finals in 2022. The thing about making picks is there’s some unwritten rule that they have to be provocative. So more than a few predictions had the Celtics winning in seven games. My first thought was, “Wait, haven’t the Celtics already played two seven-game series?” I turned an obvious question into a mini project. I looked up how many teams had played three seven-game series in one postseason and how they did in the NBA Finals. As it turns out, it’s really hard to win three seven-game series in one playoff run. The only team that had ever done it was the 1988 Lakers. I turned that into a story — not just about the trivia, but about how grueling it is to go through the playoffs.

When the Celtics lost in the finals that year, the common reaction was that they’d get another chance next year. But, I wondered how many of the teams that lose in the finals actually make it back the next year. The answer is: not a lot.

I spent a year with the Nieman Foundation for Journalism studying data and art and how they can relate to sports. I added skills to build on what I was doing. I started learning how to use R, the coding language, to wrangle and visualize data. I learned more about statistics, probability, and prediction. I learned some of the math (some!) that goes into the analytical models driving modern sports. A lot of those doodles are digital now — fun scatterplots of all the shots taken in a single season, waffle charts to show how often NFL teams score on the first drive in overtime, or grids of NBA lottery picks and whether they’re with the team that drafted them.

I look at debates differently now too. A take is just a question that hasn’t been explored yet.

For me, that’s an entry point that works, and it’s a door I think is worth walking through.