.jpg)

Gangster Squad, the secretive Los Angeles Police Department unit whose job it was to get the mob out of Los Angeles, circa 1948. Photo by Gangster Squad member Conwell Keeler.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Dealing with Hollywood”

- Paul LiebermanWeeks after I arrived in Los Angeles in 1984 a producer called and asked if I'd write a film. I sensed it wasn't supposed to be that easy but headed out to "do lunch," all the while imagining scenes for "our movie." The producer had seen a series I'd written for the Atlanta newspapers about pornography king Mike Thevis, who brought peep shows out from sin centers such as Times Square into the American heartland, blowing away rivals in the process. I laughed to myself thinking how we might dramatize porn becoming mainstream by showing a convention where XXX-rated fare was sold openly, with row after row of chocolate body parts.

By the time I arrived at the producer's office I had a few actors in mind as well. He threw out names, too—big stars!—while driving us to the restaurant in his Rolls Royce with a license plate bearing the title of his last film, a small-budget horror flick. Over burgers he said, "Let's do it!" and proposed a deal—I'd get "two points" for writing the script, meaning just a share of the proceeds, with no guarantee I'd make a dime for my work. I said, "Fine, and in the meantime you'll pay me how much?" and that was the end of our beautiful friendship, in the parlance of "Casablanca."

The Hollywood fantasy comes easily. If you produce ambitious narrative journalism it's not hard to imagine your work making it to the Big Screen, with your real-life characters played by George Clooney, Brad Pitt, and his luscious significant other, Angelina Jolie. You can write the book, sure, with a first printing of 20,000 if you're fortunate. But these days our culture's shared experiences rarely involve the printed word, the Harry Potter franchise aside. Ponder the allure of a wide-release opening weekend generating $20 million or $50 million at the box office. Why not dream big?

From the start of my journalism career, I was drawn to dramatic stories—a notorious cop killer who claimed to have been reborn in prison, a surgeon who butchered young children until other doctors around him revolted, a reclusive heiress who died mysteriously and left her $1 billion estate in care of her butler, a hospital killer who lurked on the graveyard shift, and so on. Like many cornball reporters, I found the work so rewarding I sometimes felt guilty taking a paycheck, even when earning $120 a week.

But if you generate stories like that, you don't have to do anything to get intriguing feelers—they'll ring you up, all these producers and agents looking for material, some wannabes, sure, but real ones too. So for years I found myself negotiating option deals, promoting potential mini-series, writing film treatments, and one-paragraph ("back of the napkin") pitches, along with one full script, all the while taking lots of lunches … without a single movie being made.

The daunting odds were underscored in Robert Altman's "The Player," in which Tim Robbins portrays a studio executive who kills a screenwriter whose pitch he rejected. In a scene set in a Palm Springs spa, Robbins explains to his naïve new paramour how his studio fields 50,000 submissions a year and green-lights only a dozen. "Everyone who calls … they think that come New Year's it will be just them and Jack Nicholson on the slopes of Aspen … The problem is I can only say 'yes' … 12 times a year."

Which brings us to my "yes."

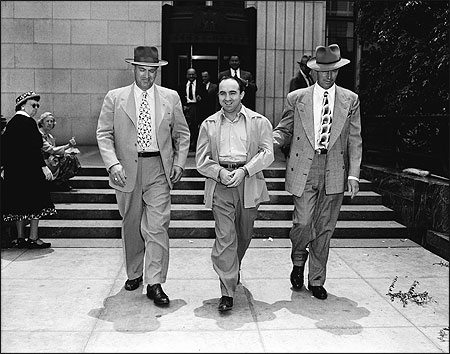

Hoodlum Mickey Cohen, center, smiled as marshals escorted him from federal court in Los Angeles, California in 1951 after he was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary for income tax evasion. Photo by The Associated Press.

From Tip to Film

I am writing this with bleary eyes after a long night on the streets of Los Angeles, where Warner Brothers is shooting "The Gangster Squad" based, with dramatic liberties, on my 2008 Los Angeles Times series about a secretive police unit given the job of driving the mob out of Los Angeles after World War II. Sean Penn plays the showboating hoodlum Mickey Cohen and Josh Brolin and Ryan Gosling, Hollywood's heartthrob of the moment, play cops obsessed with bringing him to justice or to the morgue while Emma Stone is the main love interest, caught between Cohen and the cop played by Gosling. Her character is invented, but the cops were real, the ones whose stories I began chronicling two decades ago.

In 1992, I got a call out of the blue from a reader wanting to correct an article that discussed the history of a police division accused of questionable snooping. The caller, clearly an older man, said we'd failed to mention the Gangster Squad, formed in 1946. When I asked how he knew about it, he said, "Well, I was on it." The next day I was in the living room of long-retired Sgt. Jack O'Mara, intent on getting down his stories, even if it was hard to see how they'd fit into a daily newspaper. Then I tracked down other survivors of the squad that waged a guerrilla war to keep organized crime from gaining the same foothold in Los Angeles as it had in cities back east. I kept at it for years, in my spare time, even after moving to New York to work as a cultural correspondent. When the main figures began to die off, I finally found editors who agreed that we didn't need a conventional news peg in an era when everyone was groping to find new ways to reach readers.

"L.A. Noir: Tales From the Gangster Squad" ran in October 2008 as a seven-day serial, focusing on two cops who made getting Cohen a personal crusade. One was O'Mara, who'd managed to sneak guns out of Cohen's house and etch initials under the butt plates so they could be tied to him if ever used in a murder. The second, roguish Jerry Wooters, forged a secret alliance with one of Cohen's rivals, hulking Jack "The Enforcer" Whalen, who was shot down by Cohen's crew in the closing days of the 1950's.

In the spirit of the times, I also created videos for the Web. The first day's showed evocative night shots of the city, bullet holes in vintage cars, and scar-faced Cohen, all while a deep-voiced narrator (yours truly) promised the unfolding story of "Two cops. Two hoodlums. And the killing that ended an era in Los Angeles." Some colleagues noted that it came across like a movie trailer, as if I was using the package to play "Let's Make a Deal" with Hollywood. To which I replied, "Who me?"

Of course, even the thought of cashing in that way poses ethical issues for a journalist that novelists or screenwriters don't face. I may quip about an ambitious project, "Some of it is even true," but that's a joke. The desire to have the best—or most salable—story must never undermine our responsibility to challenge even our most compelling material. I loved the renegade cop's tale of being offered a guard dog by his hulking gangster pal. Wooters said he told Whalen he didn't want any @%$# dog, "They die on you, then you're miserable," only to have the gangster come back at him with all the ways Cohen could ambush him with shotguns or plant a bomb in his car … until he had to give in: "Where do I pick up the dog?" Great stuff, almost too good, and you could run with it under the rationale, "Well, he said it." But I felt much better when I tracked down the hoodlum's sister, still alive at 90, to see if she recalled the gift dog, a Great Dane. "Yes, sure," she said, "Thor."

A commercial film, on the other hand, thrives on embellishment. I deserve little credit—none, actually—for "The Gangster Squad" getting the final "yes" that will put it in theaters across the country in October 2012. I did not even try to get the job of writing the screenplay—a partner and I once insisted on that with a comedy project about to be packaged by a leading talent agency and killed our deal. In this case, in a touch of poetic justice, Warner Brothers gave the scripting assignment to a Los Angeles cop-turned-writer, Will Beall, who had authored a gritty novel about street gangs, "L.A. Rex." With "The Gangster Squad," he understood that the studio wanted to go big, with flying bullets and fists.

In real life, the cops had Tommy guns—slept with 'em under their beds—but, no, they didn't have wild shootouts in front of the old Park Plaza Hotel, the sort of scene required if the film was going to become the Los Angeles version of "The Untouchables." Beall's muscular script helped get Penn to sign on as Cohen, a character he was sure to mold himself. After that, the rest of the A-list cast fell into place, eager to work with Penn and up-and-coming director Ruben Fleischer, known for his evocative visual style—he'd likely show spinning cartridges being ejected from the Tommy guns in super slow motion.

Another journalist selling a story to Hollywood asked me, "How much creative control do you get?" I asked back, "Do you want that on a 10-point scale or 1-to-100?" The answer in either case was "zero." You may provide plenty of memos and briefings, but basically go along for the ride … and, if you're lucky, to the bank.

Yet on the set, I've been gratified by how many of the actors and crew ask, "Did this really happen?" "What was he really like?" "Did they ever …?" I've grown hoarse answering but there's a moral to all those questions: That's why you write the book.

Paul Lieberman, a 1980 Nieman Fellow, is working on a book version of "The Gangster Squad."