Five years ago, I was nearly killed by a man I shared a home and two small children with.

As I lay in the dark, waiting for it to be safe to leave, I don’t really remember crying, or even feeling physical pain —yet. In moments of such great anguish, the mind has a strange way of distracting itself with seemingly small things. As Chinua Achebe said, it is like the man who is carrying the carcass of an elephant on his head and is searching with his toes for a grasshopper.

Related Reading

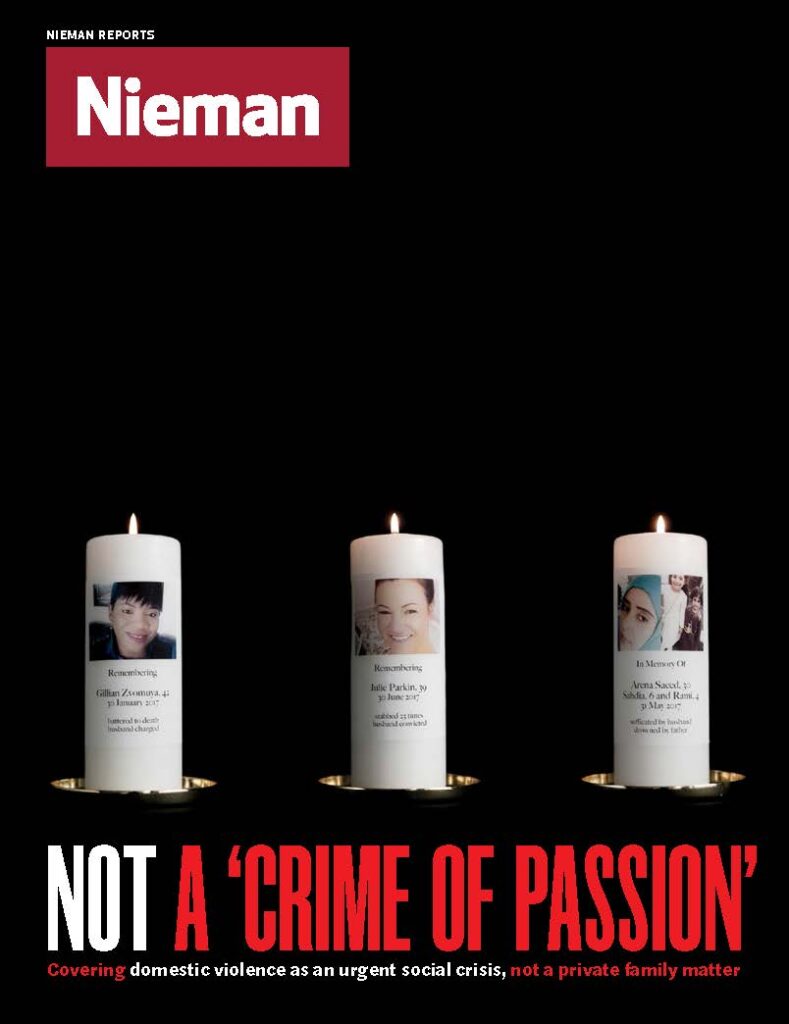

Domestic Violence Is

Not a ‘Crime of Passion’

Reporters increasingly are covering abuse by intimate partners as an urgent social crisis, not a private family matter

By Susan Stellin

Photographing Domestic Violence: Showing Uncomfortable Truths

Where is the line between respecting the needs of survivors or the deceased and the public’s need to know?

By Tara Pixley

Nieman Storyboard: From a

Caress of Love to a Fist of Fear

The New Yorker story “A Raised Hand,” by Rachel Louise Snyder, is the foundation of a new book on the scourge of domestic violence

By Ricki Morell

Domestic Violence in Turkey: No More Empathizing with the Perpetrator

More reporting that educates the public about gender stereotypes is needed

By Afsin Yurdakul

Domestic Violence in Chile:

Calling Out Femicide

There is growing pressure on the media not to romanticize femicide as a “crime melodrama”

By Paula Molina

Domestic Violence in China:

Educating the Public

A new law making domestic violence a civil infraction is increasing awareness of the abuse one in four married women have experienced

By Jieqi Luo

So that night, I remember thinking of a statistic I had just come across that week, as part of my data journalism work, that a woman is more likely to be killed by a current or former intimate partner than anyone else; more than 69 percent of women murdered in Africa in 2017 were killed by a current or former intimate partner or family member. These were no longer mere numbers to me; they had taken on a terrifying life of their own. And I remember thinking that if I died, a story could very easily be spun in which I would be framed as responsible for my own murder. I wanted to live to tell the story of that night. Most of all, I wanted my mother to hear it from me.

Mine was by no means an isolated case. In the first six months of 2019, at least 60 cases of women killed by current or former intimate partners were reported in local Kenyan newspapers.

But that’s usually just the beginning of the ordeal. Media reporting invariably tends toward blaming the women for their own deaths. Take Sharon Otieno, a 26-year-old student, who, at seven months pregnant, was found raped and stabbed to death, including a stab wound that killed her fetus in utero, allegedly on the orders of her lover, a local governor. Her gruesome murder provided fodder on talk radio for weeks, where she was vilified as a “slay queen” who deserved what came upon her, as if these were the natural consequences of being the mistress of a powerful man. [“Slay queen” is a derogatory term for women who are in transactional relationships with older, wealthy men, termed “sponsors.”]

The media should avoid falling back on the familiar, sensational tropes that frame this kind of violence as “killing for love,” or that blame women for their own deaths

In another horrifying instance, Ivy Wangechi was a sixth-year medical student who had just finished her ward rounds when a man she knew, who had been stalking her, attacked her with an ax, killing her on the spot. A number of local blogs reported that she had been killed because she had infected the man with HIV, unsubstantiated claims in several blog posts that seemed to reference each other as sources. The rumor spread like wildfire on social media. It got so bad that her family actually had to come out of mourning to set the record straight in a press conference.

On the other hand, the alleged perpetrators are typically painted with a kind, humanizing touch in media reports, and their brutal actions rationalized.

A leading newspaper ran a story with the headline “Ivy Wangechi’s killer: A quiet worker and teetotaller” the day after her murder. In media reports, the man was apparently incensed after she refused to pick up his phone calls, especially after he had sent her money on a number of occasions: “He claimed he had invested a lot in the girl but that she did not reciprocate his kindness and financial support.”

In Otieno’s case, the governor linked to her murder was arrested, but some media reports focused, for a time, on the big question of how the high profile and wealthy governor was adjusting to tough jail conditions, framed in such a sympathetic tone that he almost seemed the hero for braving it all.

Just a few weeks ago, one of the highest-rated morning radio shows in Nairobi asked, “Guys, what’s the worst thing a woman could do to make you end her life?” The question invited listeners to debate possible justifiable reasons for murder, live on radio and on their social media pages, cheerfully punctuated by banter, and advertisements for detergent and the like. It was only in the wake of outrage on social media that the offending posts were deleted after the show, but the radio hosts and station suffered no consequences.

The rationalization for this kind of murder is just part of the unrelenting physical, social and psychic violence directed toward women in Kenya, and in many other parts of the world. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 69 percent of all women intentionally killed in Africa in 2017 were killed by intimate partners or other family members. According to Kenya’s Demographic and Health Survey, among ever-married women, the most commonly reported perpetrator of physical violence is the current husband or partner (57 percent) followed by the former husband/partner (24 percent). By contrast, only about 1 in 10 men who have experienced physical violence since age 15 mention their current spouse as a perpetrator of physical violence.

These are not spontaneous “crimes of passion” or “love gone wrong” as the Kenyan media frequently frames it. Murder is often just the last and escalated act of violence against women.

Women’s lives are objects “upon which men specifically, and society in general, can inflict their hatred, derive their pleasure, and exact their ownership over their lives and bodies at will,” without regard for the rights and freedoms of women, according to activist group Feminist Collective, who are calling the crisis for what it really is —not domestic violence, or the consequence of “immorality” typified by the so-called slay queen, but femicide. It is murder that targets women specifically, a direct consequence of inequality created by patriarchy, exacerbated by a justice system that favors the powerful (mostly men), and public opinion that rationalizes violence against women. It is a tool “used to subdue women who are seen to have ‘overstepped their bounds’ at home, and in public and political spaces.”

The crisis is getting public attention, in the wake of increased pressure from groups like the Feminist Collective, and the amplification of the issue by the social media activism of ordinary people.

Groups of women in three major Kenyan cities came together on March 8, 2019, International Women’s Day, to protest against femicide in Kenya, organizing under the hashtag #TotalShutdownKE. Counting Dead Women Kenya (@deadwomen_ke) is a Twitter account that does the grim and necessary work of tracking femicide cases reported in the media.

With this kind of sustained pressure, public sentiment is growing that this is no trivial matter. Dominant media framings, as a result, are frequently being challenged in op-eds and on talk shows, especially by feminists who are calling attention to the broader misogyny and impunity that leaves women most vulnerable to violence. They have called for crimes against women to be taken more seriously and that they must be treated as actual crimes; they have called for a broader conversation that must involve men, who have a lot of unpacking and unlearning to do, especially “with their entitlement to women’s bodies, time, space, labour and energy,” said activist and lawyer Vivian Ouya in an interview with The Star newspaper.

Other voices have argued that the murders are related to rising rates of depression in men, or that it is a simply a generational crisis, in which today’s young men in particular are entitled, socially adrift, and unable to deal with rejection, and young people in general are stressed by the worst effects of poverty, limited economic opportunities, and a culture of political violence.

Still, the official —government —response has tended to disconnect femicide from broader political and economic dysfunction, as if murder is an unfortunate but merely extreme version of ordinary relationship drama. It isn’t. Violence against women escalates when impunity reigns and when political systems favor the powerful (mostly men).

Journalists should explicitly make these connections, so that violence against women is not rendered unthinkable —it is, in fact, the job of journalists to make any crisis thinkable. The media should avoid falling back on the familiar, sensational tropes that frame this kind of violence as “killing for love,” or that blame women for their own deaths. And media outlets should not get away with hypothesizing murder for the sake of entertainment, as that Nairobi radio station did.

Ultimately, it will take a much deeper national reckoning to make women’s lives matter. For me, I was fortunate that I managed to escape with my life and my children—and that my mother heard the story from me.