Ask about where to find one of the best journalism school educations available, and the answer might be a surprise. It’s happening at the Caucasus School of Journalism and Media Management in Tbilisi, Georgia, where a curriculum accelerates learning, truly develops skills, and produces graduates who work in key media positions in three countries. This curriculum also probably has zero chance of being adopted by any university in the United States. Accelerated, concentrated learning does not fit the American model.

I’ve taught at the Caucasus School and now teach at Kent State University, a school that takes a practical hands-on approach to journalism education. But no traditional American university has the flexibility of the Caucasus School, an institution designed from the ground up to train journalists. To be educated in the United States means students take a boatload of credits during a quarter or semester, rowing through multiple courses toward a fixed destination, all at the same time. What business would schedule all major projects to be concluded simultaneously, as universities usually do?

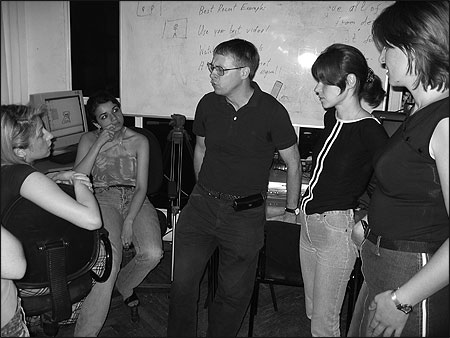

Assistant Broadcast Instructor Valery Odikadze trains students. Photo by Karl Idsvoog.

A Focused Approach to Learning

The Caucasus School of Journalism and Media Management takes a different approach. At the Caucasus School, students don’t take multiple courses at the same time. Instead, they focus on specific topics and skills for days and weeks at a time. They learn how to do journalism the same way they learned to ride a bike—by immersing themselves in the doing of it. Topics of focused work included political reporting, business reporting, computer-assisted reporting, radio reporting, newsroom management, photography and television reporting.

As part of their learning, students turn out real-world products. They publish a newspaper and produce radio stories and TV reports. They design and publish an online news site. Academic director David Bloss sums up the school’s philosophy this way: “Whenever possible this is a newsroom, not a classroom.” I’ve seen that as a result of this approach students at the Caucasus School learn faster and perform at a higher level more quickly than do students in American-style programs. And they emerge with a clear sense of the valuable societal role that journalism done right can play.

Started in 2002, the school is a joint effort by the International Center for Journalists [ICFJ] in Washington, D.C. and the Georgian Institute for Public Affairs. Founding Academic Director Margie Freaney set the tone for school’s educational direction. “We treat students like professionals, like reporters, not as students,” she explains. There are, Freaney says, two reasons for the topic-focused curriculum structure, one educational and one practical. As she says, “It’s much easier to build upon each class with successively more complicated material when the classes are intensive.”

Because the school recruits American journalists with significant experience to train its students, the program’s structure is also more efficient. Many of these U.S. journalists don’t have calendars with semester-free schedules, but they are able to go to Tbilisi to teach a two-week, month-long or six-week session. Bringing instructors in for these compressed and intensive sessions also saves money. “Having the instructor work all day every day on specific training maximizes the time you have bought,” says Bloss, who was an editor of The Providence Journal. This all-day educational structure also provides a more real-life approach to journalism training and eliminates what can be a student’s typical excuse for work not done: “I had an assignment due in another class.”

Photographer John Smock, who is the school’s publication director and layout and design instructor, is a strong proponent of this training model. For teaching practical courses in photography or design, Smock finds that short class periods are “too disruptive to the material.” He believes that longer class periods give the instructor a chance to “build the rapport necessary to teach complicated skills.”

Knight Fellow and Caucasus instructor Jody McPhillips calls this school the “gold standard” in journalism education. [She and her husband, David Bloss, spent two and a half years training journalists in Cambodia before accepting the Tbilisi assignment.] McPhillips observes that the Caucasus model develops in students a work ethic that will be critical to the students’ success once they leave the school. “Sticking to a single topic over an extended period reinforces the work ethic students will encounter in Western-style journalism,” says McPhillips. “There is nowhere to run, nowhere to hide.”

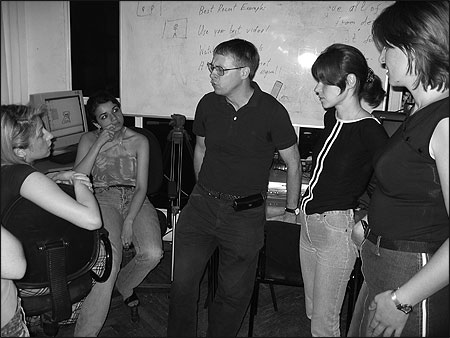

Academic Director David Bloss converses with students. Photo by Karl Idsvoog.

The Value of Longer Sessions

For instructors, too, the longer, more focused engagement with students offers nowhere to hide. Teachers can fake an hour-long lecture, but if well thought through plans aren’t prepared for daylong sessions, the class can easily start to fall apart. When an instructor arrives unprepared, Smock notes that “the students will eat you alive.”

Joyce Barrett, a journalist turned teacher who has taught at George Mason University in the United States and in several other countries, credits the Caucasus model for improving students’ skills, abilities and retention. “In my one-hour 15-minute classes, I barely get into something and I’ve run out of time,” she says, noting that longer sessions she has with students eliminate an annoying problem of clock watching. “With more time students are more relaxed and more interested in getting involved in something,” Barrett says. Longer courses shake students and instructors out of their normal routines. “This forces students and instructors alike to keep the energy level up and be more engaged and engaging,” says Smock.

With the Caucasus teaching model, students get immediate feedback— something that Smock contends is dictated by the subject matter. “Practical material such as layout and design or photography,” Smock says, “requires a lot of one-on-one interaction with students—far more than, say, an introductory lecture in 12th century Dutch painting.”

My seven-week teaching duties involved the television portion of the curriculum—shooting, editing, lighting and producing. None of my students had ever edited video before they enrolled in this course; most had never shot a camera. Because students focused their entire attention on television, they immediately applied to their projects what was discussed or demonstrated in class. By the end of the first day, every student had used the camera, reviewed their video, and then shot the camera again. By the end of day three, each student was editing. After these ground-floor exercises, they start shooting and reporting news stories. Before the second week of classes started, each had produced his/her first video news report. With an emphasis, too, placed on “media management,” the class also spends time on commercial video production in which they divided into teams and produced 30-second spots about the Caucasus School.

The school’s teaching is also software intensive given that technology is changing the news business. If a computer program benefits the work journalists do—Quark, Photoshop, Sound Forge, Final Cut are good examples—then the students learn it and use it. The longer class time they have to practice these programs—with immediate feedback from instructors—accelerates the learning curve. This means instructors spend less time teaching software and more time teaching journalism.

Those who tour the school, including educators, potential funders and diplomats, emerge with a similar impression. “We get two or three years of journalism education here into 11 months,” says Bloss. But don’t take his word for it, nor mine. See how these students learn and perform by looking at their work. Several video projects can be found at http://classes.jmc.kent.edu/Idsvoog, and the school’s online newspaper is the Brosse Street Journal, www.bsj.ge.

As a visiting American instructor, I found it a joy to work with an institution and students who share a desire and purpose in doing journalism for the right reason.

Karl Idsvoog, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, is a media consultant/trainer who teaches journalism at Kent State University.

I’ve taught at the Caucasus School and now teach at Kent State University, a school that takes a practical hands-on approach to journalism education. But no traditional American university has the flexibility of the Caucasus School, an institution designed from the ground up to train journalists. To be educated in the United States means students take a boatload of credits during a quarter or semester, rowing through multiple courses toward a fixed destination, all at the same time. What business would schedule all major projects to be concluded simultaneously, as universities usually do?

Assistant Broadcast Instructor Valery Odikadze trains students. Photo by Karl Idsvoog.

A Focused Approach to Learning

The Caucasus School of Journalism and Media Management takes a different approach. At the Caucasus School, students don’t take multiple courses at the same time. Instead, they focus on specific topics and skills for days and weeks at a time. They learn how to do journalism the same way they learned to ride a bike—by immersing themselves in the doing of it. Topics of focused work included political reporting, business reporting, computer-assisted reporting, radio reporting, newsroom management, photography and television reporting.

As part of their learning, students turn out real-world products. They publish a newspaper and produce radio stories and TV reports. They design and publish an online news site. Academic director David Bloss sums up the school’s philosophy this way: “Whenever possible this is a newsroom, not a classroom.” I’ve seen that as a result of this approach students at the Caucasus School learn faster and perform at a higher level more quickly than do students in American-style programs. And they emerge with a clear sense of the valuable societal role that journalism done right can play.

Started in 2002, the school is a joint effort by the International Center for Journalists [ICFJ] in Washington, D.C. and the Georgian Institute for Public Affairs. Founding Academic Director Margie Freaney set the tone for school’s educational direction. “We treat students like professionals, like reporters, not as students,” she explains. There are, Freaney says, two reasons for the topic-focused curriculum structure, one educational and one practical. As she says, “It’s much easier to build upon each class with successively more complicated material when the classes are intensive.”

Because the school recruits American journalists with significant experience to train its students, the program’s structure is also more efficient. Many of these U.S. journalists don’t have calendars with semester-free schedules, but they are able to go to Tbilisi to teach a two-week, month-long or six-week session. Bringing instructors in for these compressed and intensive sessions also saves money. “Having the instructor work all day every day on specific training maximizes the time you have bought,” says Bloss, who was an editor of The Providence Journal. This all-day educational structure also provides a more real-life approach to journalism training and eliminates what can be a student’s typical excuse for work not done: “I had an assignment due in another class.”

Photographer John Smock, who is the school’s publication director and layout and design instructor, is a strong proponent of this training model. For teaching practical courses in photography or design, Smock finds that short class periods are “too disruptive to the material.” He believes that longer class periods give the instructor a chance to “build the rapport necessary to teach complicated skills.”

Knight Fellow and Caucasus instructor Jody McPhillips calls this school the “gold standard” in journalism education. [She and her husband, David Bloss, spent two and a half years training journalists in Cambodia before accepting the Tbilisi assignment.] McPhillips observes that the Caucasus model develops in students a work ethic that will be critical to the students’ success once they leave the school. “Sticking to a single topic over an extended period reinforces the work ethic students will encounter in Western-style journalism,” says McPhillips. “There is nowhere to run, nowhere to hide.”

Academic Director David Bloss converses with students. Photo by Karl Idsvoog.

The Value of Longer Sessions

For instructors, too, the longer, more focused engagement with students offers nowhere to hide. Teachers can fake an hour-long lecture, but if well thought through plans aren’t prepared for daylong sessions, the class can easily start to fall apart. When an instructor arrives unprepared, Smock notes that “the students will eat you alive.”

Joyce Barrett, a journalist turned teacher who has taught at George Mason University in the United States and in several other countries, credits the Caucasus model for improving students’ skills, abilities and retention. “In my one-hour 15-minute classes, I barely get into something and I’ve run out of time,” she says, noting that longer sessions she has with students eliminate an annoying problem of clock watching. “With more time students are more relaxed and more interested in getting involved in something,” Barrett says. Longer courses shake students and instructors out of their normal routines. “This forces students and instructors alike to keep the energy level up and be more engaged and engaging,” says Smock.

With the Caucasus teaching model, students get immediate feedback— something that Smock contends is dictated by the subject matter. “Practical material such as layout and design or photography,” Smock says, “requires a lot of one-on-one interaction with students—far more than, say, an introductory lecture in 12th century Dutch painting.”

My seven-week teaching duties involved the television portion of the curriculum—shooting, editing, lighting and producing. None of my students had ever edited video before they enrolled in this course; most had never shot a camera. Because students focused their entire attention on television, they immediately applied to their projects what was discussed or demonstrated in class. By the end of the first day, every student had used the camera, reviewed their video, and then shot the camera again. By the end of day three, each student was editing. After these ground-floor exercises, they start shooting and reporting news stories. Before the second week of classes started, each had produced his/her first video news report. With an emphasis, too, placed on “media management,” the class also spends time on commercial video production in which they divided into teams and produced 30-second spots about the Caucasus School.

The school’s teaching is also software intensive given that technology is changing the news business. If a computer program benefits the work journalists do—Quark, Photoshop, Sound Forge, Final Cut are good examples—then the students learn it and use it. The longer class time they have to practice these programs—with immediate feedback from instructors—accelerates the learning curve. This means instructors spend less time teaching software and more time teaching journalism.

Those who tour the school, including educators, potential funders and diplomats, emerge with a similar impression. “We get two or three years of journalism education here into 11 months,” says Bloss. But don’t take his word for it, nor mine. See how these students learn and perform by looking at their work. Several video projects can be found at http://classes.jmc.kent.edu/Idsvoog, and the school’s online newspaper is the Brosse Street Journal, www.bsj.ge.

As a visiting American instructor, I found it a joy to work with an institution and students who share a desire and purpose in doing journalism for the right reason.

Karl Idsvoog, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, is a media consultant/trainer who teaches journalism at Kent State University.