I am fortunate. The only job I’ve ever wanted was to draw political cartoons for a living and, though it took me a lot of hard work and good luck to break into the profession, that’s what I do.

Today, I still follow a routine that began when I was 12. Every week I rough out dozens of ideas for cartoons based on news stories, conversations and overheard nonsense, all with a view towards commenting on current events and trends. Unlike my earlier efforts, now my favorite three go out to client newspapers via the Universal Press Syndicate.

Given how many talented cartoonists have been fired from newspapers—most of them without hope of landing a new job—I don’t have cause to complain about my lot. I am that rare creature, the editorial cartoonist who can make a full-time living solely from syndication. Because most syndicated artists only have a few clients, their revenue is only a small supplement to a full-time position on staff. But unlike a staff cartoonist, no single editor can fire me and, by doing so, deprive me of 90 percent or more of my income. So I enjoy a rare degree of job security.

Nonetheless, I don’t have what I really want: a job at a newspaper, where I’d work with editors and journalists on cartoons, not just about the big national news stories, but on the state and local issues that resonate so strongly with readers. As a teenager, I watched Mike Peters, staff cartoonist at my hometown paper in Dayton, Ohio, draw in his ink-stained office, and since then I have craved what I consider a real editorial cartooning job. Syndication is great for the national exposure it offers, but the chance to get that newsroom buzz easily trumps the benefits of inking in my underwear while watching Ricki Lake on the TV at home.

Auditioning for a Staff Job

My cartoons are fairly well known since they are published in more than a hundred papers. I’ve won two Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, have published more than a dozen books—a few of them successful—and attracted notoriety from Fox News and other Republican-slanted media outlets because of my work during the Bush administration. As a result, I’ve been interviewed three times for positions at major U.S. newspapers.

Those close hiring calls serve as parables for the state of the industry.

In 1995, The (Harrisburg) Patriot-News, one of my clients through syndication, flew me to the Pennsylvania capital to meet for lunch with the paper’s features editor, editor in chief, and publisher. The paper didn’t have a staffer, nor had one been fired or laid off, so it would have been a “clean hire”—no resentment from the dearly departed’s friends in the photo section. I liked the town, the people I’d be working for and—most of all—the chance to wage war with my pen and ink on the reliably corrupt politicians of the Pennsylvania State Legislature.

Though it’s possible that the decision that followed was caused by my salary request, personality or some other unknown factor, I left the meeting feeling positive about my chances at Harrisburg. Then I checked in with the features editor every few days; she told me to hang tight while they came to a conclusion.

“Rather than hire an editorial cartoonist,” she ultimately informed me,

“we’ve decided to go with a sports-writer.”

I was dense. “A sportswriter is going to draw the cartoons?”

“No, we’re hiring a sportswriter in lieu of a cartoonist. It’s a budget thing.”

The Patriot-News, in the midst of a multimillion-dollar upgrade of its presses at the time, already had six sportswriters on staff. They’ve never hired a cartoonist from the dozens of brilliant unemployed artists making the rounds, leading to a simple conclusion: It wasn’t me. One might ask why Harrisburg—not exactly a big sports town, given its lack of professional teams, colleges or universities—needs so many sportswriters. Or how a newspaper in the capital of one of the nation’s most populous and politically influential states can do without a political cartoonist. But such are the mysterious priorities of editors and publishers.

Around the same time an opening occurred at the Asbury Park Press, a central New Jersey daily whose circulation was jumping thanks to increased ad revenue from the dot-com boom. The previous cartoonist was in his mid-80’s; he retired. The editorial page editor commissioned a weekly New Jersey-based cartoon from me as a way of “trying me out” on the editorial page. Pleased with my work, he recommended to the executive editor that the paper bring me aboard full time.

Naturally, I was thrilled. New Jersey politics, not to mention the fact that so many of the state’s cities are little more than bedroom communities for New York City workers, would be great inspiration. The executive editor worked his way down a list of boilerplate questions: “What was I hoping to accomplish?” “How much did I expect to earn?” “Did I need my own office?”

Everything went satisfactorily until his final query: “Will I ever look out there”—he gestured over his shoulder down to the parking lot below—“and see protesters yelling about a cartoon that you drew?”

I told him the truth. “It’s not my intention to offend readers,” I answered, “but if an idea is worth expressing, I don’t think I should self-censor because of that possibility. Of course, I would respect your judgment if you decided not to run one of my cartoons. Anyway, I find it nearly impossible to predict what will make people angry.”

His face clouded. I knew I’d blown what should have been a neat, simple, lying-through-my-teeth “no.” But what difference did it make? Take a job under impossible conditions and you invariably get fired. Actually, I appreciated his honesty. Many cartoonists discover their paper’s editorial cowardice after it’s too late.

Most recently, I was one of four cartoonists named as interviewees for an opening, again created by retirement, at The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento is distinctly Midwestern in tone, not to mention the capital of California. What I wouldn’t give to have the new governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, to kick around! And the city, while somewhat of a bore itself, is a couple hours from San Francisco and Reno.

When I arrived from New York, however, I immediately figured out that I was being given a “courtesy” interview. The fix was already in for Rex Babin, then a staffer in Albany, New York, whose cartoons not so subtly graced the walls of two of the editors who were supposedly considering me. Babin is a good cartoonist. He has been a Pulitzer finalist. But two comments made by different editors leapt out at me.

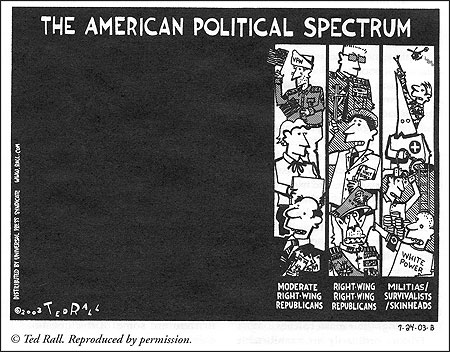

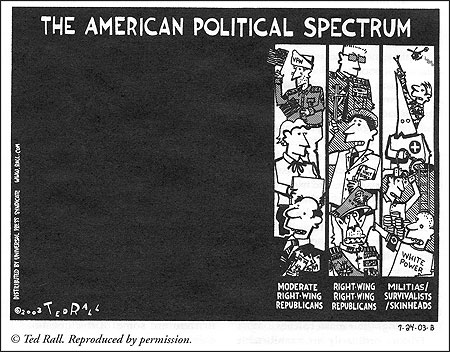

“The perfect cartoon has no words at all,” one told me. “They should illustrate the editorial page, give the reader a break from those oceans of text.”

“Sounds like you really want an editorial illustrator,” I suggested. I also do freelance spot illustrations, which are more of the eye candy this editor seemed interested in. She displayed no understanding whatsoever of what editorial cartoons are, or what they should attempt to achieve: a clear, strident, message or comment about an issue or trend—ideally delivered in a unique, thought-provoking way. Great editorial cartoons can be wordy and poorly drawn; bad ones can’t be saved by excellent draughtsmanship.

The editorial page editor, a smart, jovial man whom I would love to work alongside, put it the way I prefer: bluntly “When making this decision,” he said, maintaining the fiction that I was being seriously considered for the staff job, “I had to ask myself a question. Would the good burghers of Sacramento”—the city’s political and business elite—“prefer to read Rex Babin or Ted Rall in the pages of their morning paper?”

His primary implication that Babin isn’t as “hard hitting” as I was dubious at best. His secondary assertion—that a newspaper should cater to the delicate sensibilities of the very personalities it should treat most harshly—sums up everything that’s wrong with the media today.

But I still dream and wait for the phone to ring with the news that a paper wants to talk to me—and, maybe this time, actually hire me.

Ted Rall is a syndicated cartoonist with the Universal Press Syndicate. His most recent book is “Generalissimo El Busho: Essays & Cartoons on the Bush Years.”

Today, I still follow a routine that began when I was 12. Every week I rough out dozens of ideas for cartoons based on news stories, conversations and overheard nonsense, all with a view towards commenting on current events and trends. Unlike my earlier efforts, now my favorite three go out to client newspapers via the Universal Press Syndicate.

Given how many talented cartoonists have been fired from newspapers—most of them without hope of landing a new job—I don’t have cause to complain about my lot. I am that rare creature, the editorial cartoonist who can make a full-time living solely from syndication. Because most syndicated artists only have a few clients, their revenue is only a small supplement to a full-time position on staff. But unlike a staff cartoonist, no single editor can fire me and, by doing so, deprive me of 90 percent or more of my income. So I enjoy a rare degree of job security.

Nonetheless, I don’t have what I really want: a job at a newspaper, where I’d work with editors and journalists on cartoons, not just about the big national news stories, but on the state and local issues that resonate so strongly with readers. As a teenager, I watched Mike Peters, staff cartoonist at my hometown paper in Dayton, Ohio, draw in his ink-stained office, and since then I have craved what I consider a real editorial cartooning job. Syndication is great for the national exposure it offers, but the chance to get that newsroom buzz easily trumps the benefits of inking in my underwear while watching Ricki Lake on the TV at home.

Auditioning for a Staff Job

My cartoons are fairly well known since they are published in more than a hundred papers. I’ve won two Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, have published more than a dozen books—a few of them successful—and attracted notoriety from Fox News and other Republican-slanted media outlets because of my work during the Bush administration. As a result, I’ve been interviewed three times for positions at major U.S. newspapers.

Those close hiring calls serve as parables for the state of the industry.

In 1995, The (Harrisburg) Patriot-News, one of my clients through syndication, flew me to the Pennsylvania capital to meet for lunch with the paper’s features editor, editor in chief, and publisher. The paper didn’t have a staffer, nor had one been fired or laid off, so it would have been a “clean hire”—no resentment from the dearly departed’s friends in the photo section. I liked the town, the people I’d be working for and—most of all—the chance to wage war with my pen and ink on the reliably corrupt politicians of the Pennsylvania State Legislature.

Though it’s possible that the decision that followed was caused by my salary request, personality or some other unknown factor, I left the meeting feeling positive about my chances at Harrisburg. Then I checked in with the features editor every few days; she told me to hang tight while they came to a conclusion.

“Rather than hire an editorial cartoonist,” she ultimately informed me,

“we’ve decided to go with a sports-writer.”

I was dense. “A sportswriter is going to draw the cartoons?”

“No, we’re hiring a sportswriter in lieu of a cartoonist. It’s a budget thing.”

The Patriot-News, in the midst of a multimillion-dollar upgrade of its presses at the time, already had six sportswriters on staff. They’ve never hired a cartoonist from the dozens of brilliant unemployed artists making the rounds, leading to a simple conclusion: It wasn’t me. One might ask why Harrisburg—not exactly a big sports town, given its lack of professional teams, colleges or universities—needs so many sportswriters. Or how a newspaper in the capital of one of the nation’s most populous and politically influential states can do without a political cartoonist. But such are the mysterious priorities of editors and publishers.

Around the same time an opening occurred at the Asbury Park Press, a central New Jersey daily whose circulation was jumping thanks to increased ad revenue from the dot-com boom. The previous cartoonist was in his mid-80’s; he retired. The editorial page editor commissioned a weekly New Jersey-based cartoon from me as a way of “trying me out” on the editorial page. Pleased with my work, he recommended to the executive editor that the paper bring me aboard full time.

Naturally, I was thrilled. New Jersey politics, not to mention the fact that so many of the state’s cities are little more than bedroom communities for New York City workers, would be great inspiration. The executive editor worked his way down a list of boilerplate questions: “What was I hoping to accomplish?” “How much did I expect to earn?” “Did I need my own office?”

Everything went satisfactorily until his final query: “Will I ever look out there”—he gestured over his shoulder down to the parking lot below—“and see protesters yelling about a cartoon that you drew?”

I told him the truth. “It’s not my intention to offend readers,” I answered, “but if an idea is worth expressing, I don’t think I should self-censor because of that possibility. Of course, I would respect your judgment if you decided not to run one of my cartoons. Anyway, I find it nearly impossible to predict what will make people angry.”

His face clouded. I knew I’d blown what should have been a neat, simple, lying-through-my-teeth “no.” But what difference did it make? Take a job under impossible conditions and you invariably get fired. Actually, I appreciated his honesty. Many cartoonists discover their paper’s editorial cowardice after it’s too late.

Most recently, I was one of four cartoonists named as interviewees for an opening, again created by retirement, at The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento is distinctly Midwestern in tone, not to mention the capital of California. What I wouldn’t give to have the new governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, to kick around! And the city, while somewhat of a bore itself, is a couple hours from San Francisco and Reno.

When I arrived from New York, however, I immediately figured out that I was being given a “courtesy” interview. The fix was already in for Rex Babin, then a staffer in Albany, New York, whose cartoons not so subtly graced the walls of two of the editors who were supposedly considering me. Babin is a good cartoonist. He has been a Pulitzer finalist. But two comments made by different editors leapt out at me.

“The perfect cartoon has no words at all,” one told me. “They should illustrate the editorial page, give the reader a break from those oceans of text.”

“Sounds like you really want an editorial illustrator,” I suggested. I also do freelance spot illustrations, which are more of the eye candy this editor seemed interested in. She displayed no understanding whatsoever of what editorial cartoons are, or what they should attempt to achieve: a clear, strident, message or comment about an issue or trend—ideally delivered in a unique, thought-provoking way. Great editorial cartoons can be wordy and poorly drawn; bad ones can’t be saved by excellent draughtsmanship.

The editorial page editor, a smart, jovial man whom I would love to work alongside, put it the way I prefer: bluntly “When making this decision,” he said, maintaining the fiction that I was being seriously considered for the staff job, “I had to ask myself a question. Would the good burghers of Sacramento”—the city’s political and business elite—“prefer to read Rex Babin or Ted Rall in the pages of their morning paper?”

His primary implication that Babin isn’t as “hard hitting” as I was dubious at best. His secondary assertion—that a newspaper should cater to the delicate sensibilities of the very personalities it should treat most harshly—sums up everything that’s wrong with the media today.

But I still dream and wait for the phone to ring with the news that a paper wants to talk to me—and, maybe this time, actually hire me.

Ted Rall is a syndicated cartoonist with the Universal Press Syndicate. His most recent book is “Generalissimo El Busho: Essays & Cartoons on the Bush Years.”