Multicolored bars, one for each of the nation’s five military services, sweep across a bluish photo of the Pentagon as a buzz-cut Marine corporal announces, “This is a Pentagon Channel report ….” Except for the anchor in uniform, the news show looks like any one of a dozen cable news programs on the air these days. In a darkened control room in Atlanta, meanwhile, military contractors tweak a live shot being fed to “Fox and Friends” for an early-morning interview with an Army captain who’s been collecting soccer gear for kids in Mosul, Iraq.

The seemingly disparate operations are the latest twists in the Bush administration’s ongoing efforts to shape public opinion by going around traditional news outlets with positive stories about its policy initiatives. “We’re the house organ, we’re the megaphone for the Pentagon,” said Allison Barber, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Internal Communications, who is in charge of the Pentagon Channel (TPC). At the U.S. Army’s Digital Video and Imagery Distribution System (DVIDS) hub in Atlanta, there is a similar utilitarian philosophy. “We provide the pipe, a trough of products for national, local and military media,” said Lt. Col. Will Beckman, DVIDS director of operations.

Media observers worry, however, such efforts further colonize American news organizations, and by extension public opinion, in ways similar to the effect televised coverage sent home by embedded reporters had with its overwhelmingly upbeat but sometimes misleading accounts of the war in Iraq. And when the Bush administration was caught cranking out covert propaganda disguised as TV news stories promoting its prescription drug plan, Rob Corddry, a mock correspondent for Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show,” described the bogus government-produced segments as “infoganda,” a fusion of information and propaganda.

These new infoganda missions, if successful, could give the Pentagon taxpayer-financed links to every home in America. Both operations follow the scrapping of the Department of Defense’s (DOD) plans for an Office of Strategic Influence to spread pro-U.S. stories in foreign countries. TPC’s May launch came within weeks of the U.S. taxpayer-financed debut of the $95 million Iraqi Media Network’s Al-Iraqiya TV that, coupled with the $65 million, Virginia-based al-Hurra, Arabic for “The Free One,” and new radio services—Radio Sawa and Radio Farda—are blanketing the Arab world with American ideals as an antidote to pan-Arab nationalism.

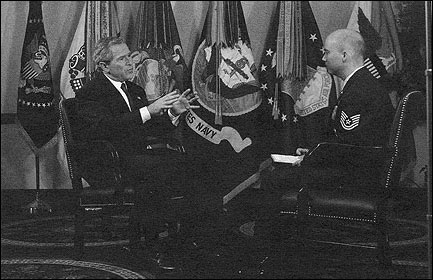

President George W. Bush answers questions during an interview with Air Force Tech. Sgt. Sean Lehman of the Pentagon Channel at the Pentagon on May 10, 2004. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jerry Morrison, U.S. Air Force/Department of Defense.

Bypassing the ‘News Filters’

Policy experts have long recognized military operations require public support because of the high cost of blood and money. American presidents set up propaganda offices during both world wars and have frequently “gone public” to try to shape public opinion. Last December, President Bush, who considers national news organizations overly negative, told ABC News’s Diane Sawyer, “I get my news from people who don’t editorialize.” As a result, the White House regularly looks for ways to bypass national news organizations, perhaps more than any previous administration. “I’m mindful of the filter through which some news travels, and somehow you just got to go over the heads of the filter and speak directly to the people,” the President told a Baltimore news anchor. “The people,” in the case of the two new operations, are America’s 1.4 million active duty troops, 1.2 million National Guard members and reservists, 650,000 civilian employees, and 25.3 million veterans and their families. “We’ve got an obligation to inform the American people about what their sons and daughters are doing,” said Lt. Col. Beckman.

Produced at a military broadcast center in Alexandria, Virginia, TPC, for years a closed-circuit feed available inside the Pentagon only, is being paid for by a $6 million supplement to the approximate $120 million a year budget the DOD spends on public information operations. TPC’s 24-hour mix of C-SPAN-style public affairs and cable TV news is also being offered free of charge to the nation’s domestic cable systems.

DVIDS utilizes portable KU-band military uplinks manned by army public affairs troops stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait and Qatar. Live shots, packaged stories, and raw footage shot by army videographers are fed to an Atlanta teleport run by Crawford Communications and then relayed at no charge to networks or local stations.

Story content for both services ranges from the topical to the journalistically dubious. Airtime is as likely to be devoted to a gritty profile of combat medical teams as it is to so-called “happy face” features, such as a soldier dressed up as the Easter Bunny, or infantry grunts rescuing a kitten trapped inside a marble column at Saddam’s former Al Faw palace. Slogan-like sound bites are commonplace. A medical chopper pilot is quoted in one story saying he returned to Iraq because “it’s part of being an American.” Not surprisingly, reports echo the pro-war sentiments of the administration and its official strategy asserting a right to unleash “preemptive” military action, if threatened.

To visually support this narrative, high-tech weaponry is showcased. Triumphant superheroes are shown decked out in night-vision goggles, blitzkrieging across the desert. The humanism of U.S. troops is also emphasized, as combat surgeons save dying children and military engineers patch up shattered schools and rebuild power plants. In keeping with Pentagon policy, however, there are no shots of wounded or dead Americans, nor bloody pictures of insurgent turmoil, such as burning fuel convoys or the grisly car bombings.

What is most striking is the absence of any opposing views. Since both media services are regarded as in-house public relations tools, Pentagon officials claim they are exempt from the 1917 Gillett Amendment and the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act, both of which prohibit government propagandizing of U.S. citizens, along with DOD directives that prohibit “censorship or manipulation” of news broadcast to American forces.

Since it first served Union troops in the Civil War, the storied The Stars and Stripes newspaper, with its circulation of more than 60,000 and a readership of perhaps twice that, has practiced a battle-tested tradition of editorial independence and balance in reporting military news despite the fact it falls under the control of the same DOD office that runs TPC. Similarly, the American Forces Radio and Television Service (AFRTS) rebroadcasts, uncensored, to military audiences overseas the nightly newscasts of the major networks. TPC, however, follows an apparent editorial policy of telling half the story. For instance, on the day kidnapped U.S. Army Specialist Keith Maupin appeared in a videotape shown by the Arab satellite network Al Jazeera, and broadcast by the four over-the-air networks along with Fox, CNN and MSNBC, TPC newsbreaks ignored the story. Likewise, although TPC broadcast news conferences, briefings and congressional hearings that explored the Abu Ghraib cruelty allegations, its news programs ignored the controversy.

Pentagon officials turn aside charges of selective bias. “We’re so not a breaking news channel, that’s not even part of the goal,” said Barber. “Everything we do is command information.” But one military official, who wanted to remain anonymous due to his unpopular perspective, described the network as a “humorous and pathetic” attempt to inhibit the news flow to military personnel.

Among former civilian journalists who now work for the DOD, there is support for the effort. “I see nothing wrong with the DOD attempting to provide the people that work for it with news and information,” said Bob Jones, chief of electronic news for the Air Force News Service and a former regional bureau chief for CBS News. “You don’t see on the Pentagon Channel any of the military attacks on Fallujah or Baghdad. By the same token, you don’t see a wealth of stories about soldiers playing soccer with kids or building schools in Iraq on the CBS Evening News. That’s the kind of story that needs to be told.”

In a close presidential election, telling the story in the way one wants it to be told can become potentially critical, considering it was absentee military ballots in Florida that delivered the 500-vote margin that sent Bush to Washington. Military personnel are thought to be two-to-one Republican, but a Battleground Poll this summer showed 41 percent of veterans and 42 percent of veteran’s families disapproved of the way the President is handling his job.

Barber, a veteran Republican political operative, denies the Pentagon Channel is meant to craft a positive image of the U.S. military in an election year. But what ends up on the air undercuts, at times, her apolitical stance. In a May 10th interview with Bush, TPC anchor, Air Force Tech Sgt. Sean Lehman, referring to the Abu Ghraib photos, asks the President, “How do we set that aside and continue what we need to do?” Later in this interview, President Bush claims Iraqis are “sitting there watching this election process of ours,” and implies Iraqis are rooting for him, declaring “they want to see if I’ve got what it takes to stand up to the political pressures and do what I think is right.” His assertions go unchallenged.

There are also questions about the intent and reach of these media operations. A DVIDS memo recommends “engaging the news media and key [non-military] audiences … with aggressive, forward-leaning tactics,” while internal memos and an early feasibility study encouraged TPC planners to pursue becoming the “default viewing choice for the military community.” One message even discusses a “campaign” to get troops, veterans and military retirees to pressure private cable operators to add TPC.

What impact are these efforts having? As of mid-July, DVIDS had produced 92 live shots and fed raw footage to a variety of clients, including all the major U.S. over-the-air and cable news networks and a handful of local stations. In addition, DVIDS supplied more than 2,700 still photos to commercial and military newspapers, including one shot that ended up on the front page of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. While the newspaper credited the military photographer, most television segments failed to mention that the military was the source of its material.

Only a handful of domestic military installations have added TPC to base cable systems while few, if any, of the nation’s 10,000 cable providers have put TPC on their lineups. “I wonder about the effectiveness of it based on exposure,” said Jones. “Who’s going to be seeing this and how are they going to see it?”

These questions remain unanswered, as does the future of these enterprises should the election in November bring in a new administration. Both operations have purchased only a year’s worth of satellite time to transmit programming. What is most significant about these Pentagon efforts is not their impact but their intent. At a time when justification for the war in Iraq is spoken of in terms of democratic ideals of truth and free expression, this purposeful creation of “infoganda” outlets that obscure reality by reporting sanitized half-stories to America’s fighting forces and citizens strikes an odd pose with the administration’s lofty rhetoric about freedom.

Charles Zewe is a doctoral candidate at the Manship School of Mass Communications at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He is a former correspondent and anchor for CNN. In Vietnam, Zewe was a U.S. Army public affairs correspondent before becoming a local TV anchor in New Orleans where he covered the U.S. invasion of Grenada and guerilla fighting in Central America. While at CNN, he was among the network’s teams of reporters assigned to cover the 1991 Gulf War and the deployment of U.S. troops to Bosnia in 1996.