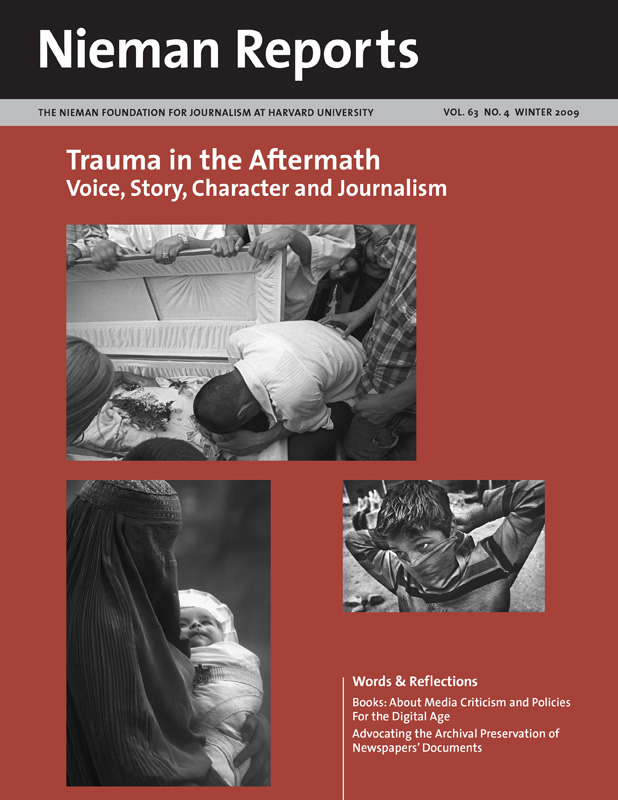

Bombings in Iraq happen frequently, with tragic effects, for Americans and Iraqis. Photo by The Associated Press.

On September 4, 2007, a roadside bomb in eastern Baghdad killed three soldiers, destroyed the legs of a fourth soldier, and left another, Duncan Crookston, with some of the war’s most catastrophic injuries. Washington Post correspondent David Finkel captured the moment and its aftermath in “The Good Soldiers,” his account of the 15-month deployment of the 2-16 infantry battalion, nicknamed the Rangers. It was published by Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

In this excerpt, Duncan’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Kauzlarich, visits him at Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) in San Antonio, Texas while on home leave in January 2008. It was the first time he had seen him since the explosion in Iraq. The scene begins as Kauzlarich is walking down the hall with Duncan’s 20-year-old wife, Meaghun, and his mom, Lee. Fellow soldier Michael Anderson was with Duncan in Baghdad on the day of the explosion.

They began walking down the hallway now, toward Duncan’s room. Four and a half months later, there was still so much about September 4 that Lee and Meaghun didn’t know. That Duncan’s platoon circled up and prayed before every mission. That his body armor was still on fire when he was loaded into a Humvee. That his hands were so black that Michael Anderson thought he was still wearing his gloves. That as Anderson cradled his head in the back of the Humvee, Duncan, hair and eyebrows and so much else of him gone, began to talk.

In April 2010, "The Good Soldiers" received the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize, awarded by the Nieman Foundation and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. David Finkel was also interviewed by the Nieman Storyboard in May.

“Who is this?”

“It’s Anderson. Can you hear me?”

“How’s my face?”

“Don’t worry. It looks good.”

“Ow, it hurts. It hurts. It burns. And my legs hurt.”

“Don’t worry. Don’t worry. I got you. Just rest your head in my hands. It’s okay. It’s okay.”

“Give me some morphine.”

“It’s okay.”

“Morphine.”

“It’s okay.”

“I want to go to sleep.”

“Stay awake. Don’t close your eyes.”

“I want to go to sleep.”

“Keep talking to me, buddy. You love your wife, right?”

“I love my wife.”

“Well, don’t worry, man. She’s gonna be waiting for you, man.”

“I LOVE MY WIFE.”

“You’re safe. You’re here with us. We got you.”

“I LOVE MY WIFE. I LOVE MY WIFE.”

“Nothing’s gonna happen to you. You’re safe. You’re fine.”

“I LOVE MY WIFE. I LOVE MY WIFE.”

He shouted that again and again, all the way to the aid station. They didn’t know that, either, but from the moment he reached BAMC, they knew every thing from then on, because this was their life now. His infections. His fevers. His bedsores. His pneumonia. His bowel perforations. His kidney failure. His dialysis. His tracheotomy for a ventilator tube. His eyes, which for a time had to be sutured shut. His ears, which were crisped and useless when he arrived, and subsequently dropped away. His 30 trips so far to the operating room. His questions. His depression. His phantom pains, as if he still had two arms and two legs.

“I mean, we weren’t even married for a year,” Meaghun said as they neared the room.

“I know,” Kauzlarich said, and now he was looking through the window at the sight that Anderson had called honestly creepy, but even that didn’t begin to describe what he was seeing. There was so much of Duncan Crookston missing that he didn’t seem real. He was half of a body propped up in a full-size bed, seemingly bolted into place. He couldn’t move because he had nothing left with which to push himself into motion except for a bit of arm that was immobilized in bandages, and he couldn’t speak because of the tracheotomy tube that had been inserted into his throat. Every part of him was taped and bandaged because of burns and infections, except for his cheeks, which remained reddened from burns, his mouth, which hung open and misshapen, and his eyes, which were covered by goggles that produced their own moisture, resulting in water droplets on the inside through which he viewed whatever came into his line of sight. “Bastards,” Kauzlarich said quietly as into those droplets Meaghun now appeared.

“Do you want the music on or do you want me to turn the music off ?” she asked, and when there was no response from him, she patiently tried again.

“Do you want me to turn it off?”

No response.

“Off?” she said.

No response.

The room was hot. The sounds were of the ventilator, IV drips of pain medication, and monitoring machines whose beeps and numerical readouts were the only indication that inside those bandages life continued to go on.

Now Lee swam into Duncan’s view.

“Is that better?” she said as she put a pillow on the board that was supporting the remains of his arm.

No response.

“Yeah?” she said as she fluffed it into shape.

No response.

And now it was Kauzlarich.

“Hey, Ranger buddy. It’s Colonel Kauzlarich. How are you doing?” he said as he stood at the side of the bed.

No response.

“You hanging in there?”

No response.

“Can you hear him? Yes or no?” Meaghun said.

No response.

“All the guys in Iraq want to let you know that they appreciate what you’re doing,” Kauzlarich said. “I appreciate what you’re doing.”

No response.

“We’re doing good. We’re winning,” he said, and soon after that, after listening to Meaghun talk about Duncan’s upcoming twentieth birthday and their plans to someday live in Italy, and then listening as she suctioned saliva out of his mouth, he left, promising to be back.