Anna Fifield, a 2014 Nieman Fellow, started thinking about writing a book about North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un, after she returned to the region as The Washington Post’s Tokyo bureau chief, covering Japan and the Koreas, following her Nieman year. It was her second go at covering North Korea—she had done so for the Financial Times, from 2004 to 2008—and she was shocked to see how much had changed in the time she was away.

“When I returned, I was astonished to see how North Korea had changed and grown stronger. The economy had improved. Kim Jong Un had defied all of the expectations to hold onto power,” says Fifield, who was posted in Tokyo from 2014 to 2018. She had no idea, however, that her 2016 book proposal about the elusive leader would become so timely. “When I started working on the book, I could never have imagined that it would become so topical or that he would have embarked on this diplomatic process. That was pretty fortunate.”

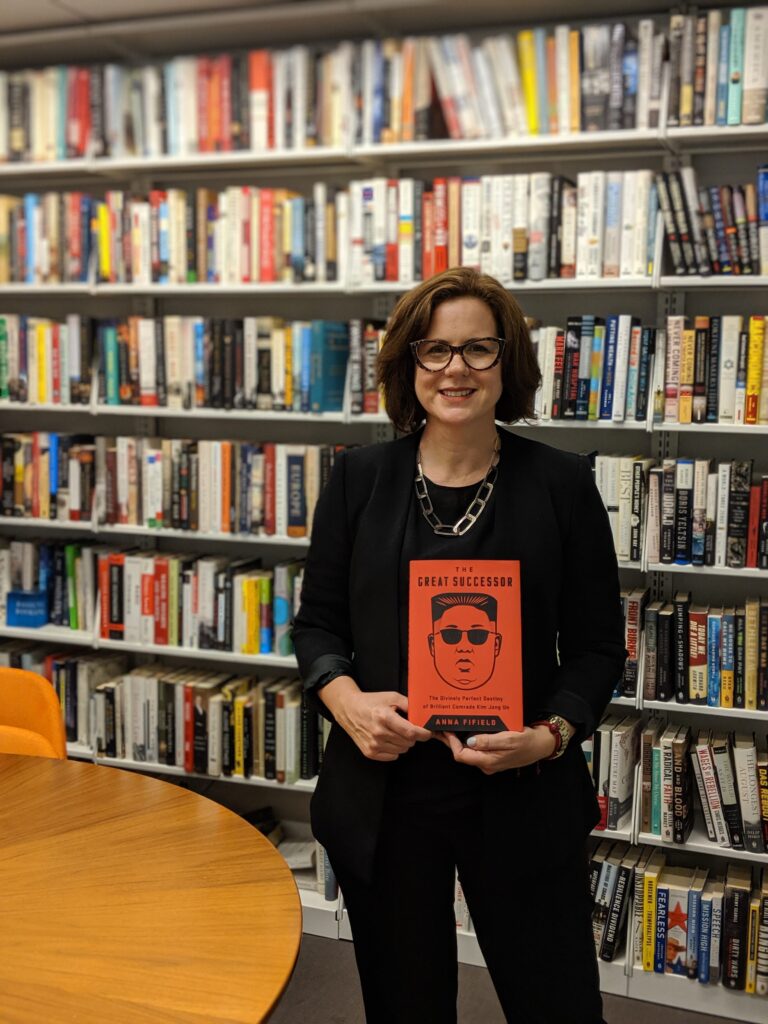

Fifield would wake up at 4 a.m. to work on her book, her writing often interrupted by the regime’s ramped-up missile tests—“Kim Jong Un kept launching missiles at five o’clock in the morning which was really inconsiderate of him”—in 2017. The end result, her new book “The Great Successor: The Divinely Perfect Destiny of Brilliant Comrade Kim Jong Un,” was published June 11 by PublicAffairs. The in-depth look at the reclusive young dictator grew out of Fifield’s many years covering North Korea, including a dozen trips to the restricted country, both before and after he succeeded his father in 2011.

Nieman Reports talked with Fifield, who is now the Post’s Beijing bureau chief, about the challenges of reporting on North Korea and Kim Jong Un, both while visiting the country and from afar. Edited excerpts:

Over the course of your years covering North Korea, what has changed in terms of journalistic access?

Quite a lot has changed, but many things have stayed the same. There is still absolutely no freedom to report whatsoever. When reporters get to North Korea, the regime minders are there with us at all times. The authorities decide where we go, where we stay, what we eat, who we talk to. Even when you’re in a public place, like in a square or a sports stadium, you can’t freely talk to people.

Partly because the minder will be there, but also it’s just dangerous for the people to have contact with a foreigner like that. I don’t try to do it because it puts that person in jeopardy.

One thing that North Korea is increasingly doing is taking journalists along on these huge trips. The first time I went, I went into North Korea by myself for two weeks in 2005. That was great because I did have a little bit of flexibility. The last trip I went on was with 130 journalists, all moving in a convoy.

I do try to shape my reporting trip though. I’m always asking, “Can I go to an amusement park?” or “Can I go interview an economics professor at the university?” or something like this. I ask for things that I think are reasonable. I never say to them, “Can you take me to a gulag and show me what it’s like?” I do say things that I think that they’ll give me, but then it’s constantly “No, no, no...”

How has your thinking on how to cover the regime evolved?

I have tried to go to North Korea as much as possible because I do think there is some value in going there, even though it is very much a Potemkin capital, a showcase capital. For me, all of the real reporting and the new information has all been uncovered outside of North Korea. It is on the border between China and North Korea where you can talk to traders and these very, very recent escapees from North Korea who are living and hiding there.

I’ve been in Thailand and Laos on the escape route out from North Korea. I’ve been able to talk to people unfettered who lived in North Korea until a week before. I feel like the best way to report on North Korea is not actually from North Korea. It’s through this very fresh and unfiltered testimony that reporters can get the truth about North Korea.

How do you separate the wheat from the chaff and determine what’s true?

I think that because North Korea is such a closed country and it’s so difficult to get information from them, and because the leaders have had a bit of a penchant for the weird, there’s this tendency to report any old thing about North Korea without trying to check it at all.

I don’t rush to report, like the executions that were reported a week ago and now the reports seem to be wrong. I think it’s better to be careful and slow rather than fast and wrong when it comes to North Korea.

I remember there was the story that Kim Jong Un’s uncle was fed to a pack of 120 starving dogs, which sounded completely ridiculous, even for North Korea. That story took off around the world. It turned out to be based on a Hong Kong version of The Onion.

What are some of your techniques for understanding North Korea?

I talk to a really wide range of sources. If I was going to write something about the North Korean medical system, for example, then I’d want to talk to diplomats or foreign residents who’ve been there, who’ve been into hospitals, to aid workers, and to knowledgeable people who have escaped from North Korea, like doctors or people who have been in hospitals. Also, I’d look at what the North Korean official literature says about these kinds of things. There’s a lot of piecing together.

One of the most important things—and this will sound so obvious—that I have done is to ask people about things that they might actually know about. There has been this tendency over the years for journalists to latch onto any North Korean escapee, to ask a farmer from the northern part of North Korea about the nuclear program or ridiculous questions that you wouldn’t expect them to know about.

When I talk to North Korean escapees, I always ask them about their daily lives. I ask them to tell me what their house or their village was like, what food they bought at the market, and how much it cost. Things very much about their lives and their personal experience of the system.

The biggest challenge that has happened since I started covering North Korea is that there has become an industry for defector testimony. In particular, Japanese and South Korean journalists pay North Korean escapees for their testimony. There’s a whole bunch of TV shows in South Korea now where North Korean defectors appear, and they get paid for it. Some people get $300 for an interview. That has created a market for more and more sensational stories about North Korea, which has encouraged some defectors to exaggerate their stories. That’s an alarming development.

Of course, I cannot pay defectors so that makes it even more challenging. I did a project for The Washington Post where I needed to talk to 25 people who had lived under Kim Jong Un’s regime. To get those 25 who would agree to talk for free, we had to approach more than a hundred people.

Getting people who are willing to spend time with me and answer all of my questions without any remuneration, I think, means that they’re doing it for the right reasons. Or for the same reasons that I’m doing it, which is to try to shed light on what life is really like in North Korea. In recent years, there’ve been a number of books and stories that have later turned out to be either fabricated or exaggerated—partly because the escapees themselves want to exaggerate their stories to make it more attractive for people to listen to and also, I think, because people have come to expect increasingly lurid tales from North Korea.

Just the normal, old, day‑to‑day banality of evil kind of thing doesn’t seem quite so gobsmacking anymore. When in reality, almost of all of these people have really horrific stories. There is no need for anybody to exaggerate anything about it.

For international media, whether it’s in the U.S. or elsewhere, do you think it’s essential that journalists try to focus more on the everyday lives of North Koreans, rather than just the big headlines about Kim Jong Un and nuclear powers?

I think it’s really important, because there is a tendency to see North Korea as monolithic, and to treat all North Koreans as if they are weird robots, who are the subjects of this dictator with the weird haircut.

I have tried to write about ordinary people in North Korea, because they are the first and the biggest victims of Kim Jong Un and the recipients of his threats on a daily basis. I have tried to show the human side of life in North Korea, and to show that people in North Korea are not brainwashed automatons. In many respects, they are just trying to make ends meet, make sure their kids do well in school, and that they get ahead. The same as all the rest of us on the outside world.

This is a really difficult thing. It’s very, very time‑consuming to find people who have escaped from North Korea and to gain their trust.

[That said,] there is lots of great reporting [on North Korea by U.S. and international outlets], including in South Korea. There’s an outlet called Daily NK that is doing a lot of this kind of journalism. They have citizen reporters inside North Korea or informants who can tell what's going on in there. They are providing a lot of information about what’s happening in North Korea.

When reporting on North Korea from afar, how much can you rely on “experts,” whether they’re academics, policy figures, or politicians, etc.?

It depends on who it is. There are leadership analysts in South Korea who, all they do, is study the regime. They read North Korean statements. They have contacts. They are following this very, very closely. I am going to approach them, not a nuclear expert, about changes in regime dynamics.

In South Korea, North Korea is a very political issue. Often, what analysts or government officials will say is colored by their political stripe. That is something that I do take into account. For example, the intelligence service in South Korea has a very, very patchy record when it comes to being right about things. I always take what they say with a grain of salt.

During your Nieman fellowship year in 2014, your study plan was to examine how change occurs in closed societies like North Korea and Iran. While at Harvard did you learn any particularly important lessons that proved valuable in covering North Korea?

One of the courses that I audited was a comparative politics course. Some of the readings that I did during that course—with professor Steven Levitsky—were influential, in terms of thinking about how rising expectations need to be sustained or the population might start to revolt. I’m thinking about the French Revolution. The French Revolution happened because people had an expectation that their living standards would continue to rise. I also did a Middle East politics course at the Kennedy School. That was not focused on North Korea, obviously, but looked at different kinds of regimes and how they manage to stay in power. That course was also interesting and relevant to what I then went on to report on in North Korea.

Are you optimistic about the future of North Korea?

Well the best thing for the people of North Korea would be to be free of this dictatorship. I’m not optimistic about that happening any time soon. Kim Jong Un seems to be very much in power. Although, of course, no one saw the collapse of the Soviet Union or the Arab Spring coming.

In the meantime, I don’t see much prospect of change, because there’s no sign that Kim Jong Un is anything but completely in control there. That’s the conclusion I draw in the book, that he has a strong grip on this regime, and that it’s not going anywhere anytime soon.