At the end of 2001, I drove west over the George Washington Bridge, into homeland America. Fifteen weeks had passed since I’d stood on my uptown rooftop and watched the second tower fall. That day my gaze was drawn beyond the New Jersey Palisades; I wondered about the middle of the country. I knew that a genie had been uncorked, that we were about to see new evidence of what novelist Philip Roth calls the “indigenous American berserk.”

I drove thousands of miles and talked with hundreds of people in the next few years. There was anarchist Katie Sierra, 15, in West Virginia, who wore a protest T-shirt to high school and ended up with a city hating her. There was Dean Koldenhoven, 67, the Republican mayor of a Chicago suburb who stood up for Muslims and paid a heavy price. There was a white nationalist who said he’d work with Farrakhan to fight the Patriot Act.

My photographic collaborator, Michael Williamson, and I had spent more than a quarter of a century documenting America. That work was merely preparation for “Homeland.” I wrote it as if the future of our country depended upon it, and I don’t mean this in a self-aggrandizing way. Our nation’s fate depends on what all of us do journalistically in the next few years. There is the obvious watchdog reporting needed in Washing-ton—but of equal importance, all across America, journalists must document the fear and anger that is driving our nationalism.

Dale Maharidge, a 1988 Nieman Fellow, is currently working on a book about a small town in Iowa. “Homeland” was published by Seven Stories Press in May 2004. Maharidge has had four books published, including “Homeland,” with Michael Williamson, a staff photographer at The Washington Post. One of those books, “And Their Children After Them,” won the 1990 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. Maharidge will be teaching at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in January.

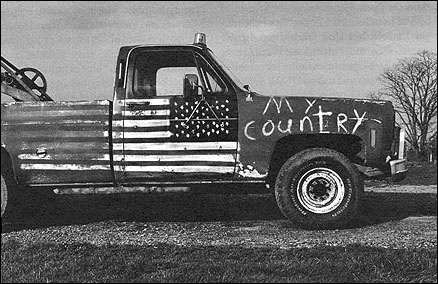

A farmer's truck, painted after a neighbor's son was killed in the Iraq War. Winchester, Virginia.

Bonneville Salt Flats. Tooele County, Utah. Photos by Michael Williamson.

These excerpts and photographs are from Dale Maharidge’s book, “Homeland.”

Flags snapping. From poles. Antennas.

USA.

Freedom.

You can choose between any of one newspaper in most cities. You can choose between any two bookstores. Any of three office supply outlets. Any Wal-Mart. Home Depot. Or Lowes. A Big Mac. Whopper. Fries.

Freedom. Just another word for nothing left to choose.

Flags were for sale everywhere. In the weeks after 9/11, they were simple flags in the form of peel-off decals and cloth. Sales were brisk. But by that December, truck stops across the country uniformly reported to me that sales had fallen.

Within a year, manufacturers got creative. At a Sheetz gas station in Breezewood, Pennsylvania, we found a box of flag motif window-stick decals at $2.99 each. They were the size of an open hand, with rubber suction cups used to affix them to auto and truck glass. These were exactly like the Baby On Board decals one saw in car windows during the 1980’s:

- Don’t Mess With The U.S., with a fighter jet in the middle

- Peace fingers, the Churchillian V for victory, in red, white, and blue

- God Bless America

- These Colors Don’t Run

- No Nukes, in the center of a circle with a slash through it

- Justice Will Prevail

- America Stands Tall

- Let’s Roll

- Proud To Be American

The manufacturers hedged bets—a little. The results of the “decal poll”: of the 16 decals in the box, three were “liberal,” in the form of two No Nukes and one “peace fingers.”

USA. Land of the Free. Pee in a bottle if you want the job. Cameras watch. From bridges. In rest areas. Malls. At work.

“For your protection.”

We must truly be free. If they watch over us so carefully. …

I certainly had no answers. What did anyone really know? In that fall and winter of 2001, all I could do was watch and talk and absorb the anger and confusion, and try to make sense of the nationalism I was seeing in the angry citizens.

The rally with the rawest display of nationalism happened just a week before Christmas 2001, on West 49th Street across from the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center. It was a Saturday, the streets jammed with tourists who’d come to watch the skaters on the ice rink, to drink hot toddies—not to see several hundred ANSWER [Act Now to Stop War and End Racism] people and others penned in by a ring of cops.

The mood was ugly. As a hostile bystander argued with a protestor, calling him a traitor, another man began screaming from the other side of the barricade.

“Get the fuck out of the country! Get out!” Josh bellowed to the gathering protestors. He was red-faced, sputtering. I asked Josh why he was here.

“I was down at Ground Zero. I’ve seen a lot of fucking friends die.”

Josh is a paramedic. He told me and my friend, photographer John Trotter, about how he waited to help survivors at a base medical center set up at Liberty Plaza for casualties that never came. In the weeks that followed, he spiraled into a depression. He rolled up his left pant leg, showed a tattoo: 9-11-01 in blue, two-inch numbers.

“Take a fucking picture of that,” he said. John did. “Day of infamy. And people out here protesting. The cops that died. The firefighters. People who cleaned shit for a living, making $300 a week. What happens? They’re dead. There’s still more to come. There are sleeper cells here.”

The protest began. Josh resumed screaming at a series of speakers. A cop nudged Josh across 49th Street. American flags waved in the breeze above a Santa Claus ringing a bell. A speaker talked about justice, not war.

“Justice, not war!?” Josh sputtered. “What does that mean? It doesn’t make any sense!”

The passersby rooted him on.

“You tell them!”

A speaker now said, “No to scapegoating of Arab-Americans.”

“What planet is that guy on?” a passerby asked loudly to a companion.

Now someone sang a civil rights song about marching on Montgomery and Selma. Then a few people unfurled a Mumia Abu-Jamal banner on two poles. Suddenly, Mumia’s face was grinning directly at Josh across the street.

“There’s a cop killer right there! A convicted cop killer!”

Josh positively gyrated.

“Don’t you have a brain?”

A woman speaker talked about the 1960’s.

“Different time, lady!” Josh hollered.

The message was locked in the past. There was little about the present. This went on for a long time. The reaction of the crowd was not simply dislike. It was seething.

“How can you allow them to do this!?” one woman screamed at a cop. The people in the crowd were ready to abandon the U.S. Constitution. The Bill of Rights. Give up everything America stands for. And this wasn’t only happening in New York.

… The crowd was angrier than it had been an hour earlier. A speaker talked about the Afghan bombing, asking, “Does it justify killing innocent children?”

“It does justify it!” a woman walking behind Josh barked.

These comments came not from rednecks, but geeks and little blue-haired ladies who suddenly sprouted Freddie Krueger voices.

But the biggest boos came not from the loudest speakers. When Michael Ratner, an attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights took the microphone, he talked quietly about America’s role in the world. He asked why we are hated, about how our policies are affecting impoverished people across the globe.

“We’re creating terrorists,” Ratner calmly said. “We have to look at why.”

The crowd across 49th Street went ballistic, all the way back to the tree half a block distant. The Santa stopped ringing her bell and waved a fist, shouting. It was mean and nasty.

“Boo! Boo! Boo!”

A spontaneous cheer went up.

“USA! USA! USA!”

It sounded like a football crowd.