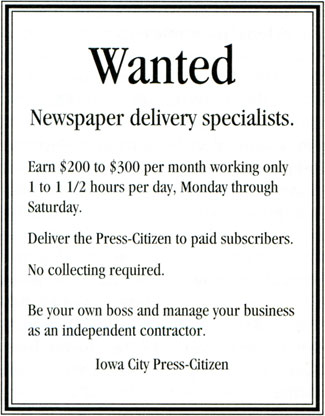

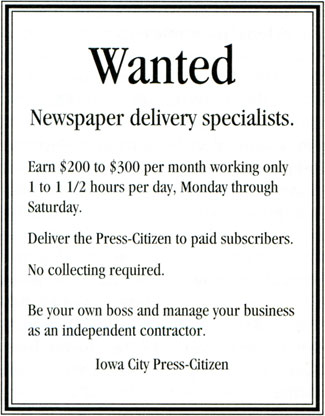

My local newspaper, The Iowa City Press-Citizen, advertises: “Paper carriers are independent businesspersons, buying newspapers at wholesale, selling them at retail and pocketing the profits. And…the profits can be substantial.” To make sure kids don’t pass up this lucrative offer, it adds: “All ages from 10 to 99 can be a carrier.” However, the ad doesn’t mention that these carriers, not the newspaper, assume the full risk for any injury that might occur while they are delivering the paper. These injuries can be substantial, as can the medical bills.

The fate of 13-year-old Stephen Johnson, who was gravely injured by a car while delivering The Dubois (Penn.) Courier, illustrates the danger this job can entail and what can happen when accidents occur. Even though The Courier paid Stephen five cents for each paper he delivered and the subscribers wrote their checks to The Dubois Courier directly—which meant that Stephen handled no money—Pennsylvania’s appellate court held in 1993 that as a “self-employed businessman” Stephen was, as the paper argued in court, unprotected by workers’ compensation. The court’s legal finding rested on the assertion that the boy “was essentially acting as a delivery service such as UPS or Federal Express.”

An example of an ad newspapers commonly use to recruit carriers.

Children as Carriers: Working Without a Safety Net

Lack of workers’ compensation coverage means some injured carriers, including children, don’t receive the medical or rehabilitative treatment they need. In other cases, they or their parents confront large hospital bills that injured employees in other sectors never do because they are paid for by the industry and consumers.

The same year as Stephen’s lawsuit, a judge in another case rendered a very different opinion. In this case a 12-year-old girl was struck by a car while she was delivering The Fremont (Neb.) Tribune and put into a permanent vegetative state. This judge, who was the first to review the workers’ compensation claim, wrote (in regard to The Tribune’s policy of using young children to deliver papers): “It is beyond sophistry and closer to outright dishonesty to characterize a 10-year-old party to a contract as a ‘little merchant’ and thus an independent contractor.”

This judicial reasoning didn’t stop The Fremont Tribune from continuing to litigate this case, arguing that it should not be held responsible for the medical expenses related to this girl’s accident. The Tribune took the case up to the Nebraska Supreme Court, and three publishing associations and two newspapers supported its cause by submitting friends of the court briefs. And as the case worked its way through the courts, the Nebraska Press Association prevailed upon the state legislature three times to kill proposed amendments to the workers’ compensation statute to extend benefits to carriers.

Evidence in this court case showed that The Tribune told carriers when to deliver the paper, how to band and “porch” it, how to deal with customers who stopped subscribing, and prescribed collection methods and appearance standards. Despite this obvious control, the paper claimed that Larson and carriers as young as 10 were “merely subscribers of the newspaper” who happened to resell it. When I asked about this apparent contradiction, Mary Sepucha, Director of Employee Relations at the Newspaper Association of America, chanted the mantra that publishers have rehearsed for a century: “But they’re not our employees, they’re independent contractors, and we’re not responsible for them.” More brazen still was the response of Sandra George, Executive Director of the Wisconsin Newspaper Association: George justified The Tribune’s litigation by contending that the paper simply “had nothing to do with” Larson’s injury.

These kinds of self-exculpatory statements from newspaper publishers result from their decades-long, successful campaign to exclude newspaper carriers—even children—from coverage under their workers’ compensation plans. And members of the community are rarely brought face-to-face with these child labor issues because the parties with the most to gain by public ignorance—the newspapers—have the ability to control whether this news is considered fit to print. For example, when publishers contest workers’ compensation coverage for seriously injured child carriers, no public relations disaster results because those who read their newspaper rarely know that such a case is going on. Nor are most people likely to be aware that from 1992 to 1997, 99 news vendors were killed on the job, 11 of them under 18 years old. Non-fatal injury rates among the nation’s 405,000 carriers, nearly half of whom are youngsters, are not even tracked.

Workers’ Compensation: The Publishers’ Perspective

Workers’ compensation rests on the principle that job-related injuries represent part of the cost of production and distribution of products; employers insure workers against such economic losses and recoup the insurance cost from consumers. Since the turn of the century, the movement to ensure that employers provide workers’ compensation has highlighted the need for run-of-the-mill workers to have such coverage since they lack the ability to charge consumers directly for the cost of their job-related injuries. But newspaper publishers have also been working hard to persuade legislatures and courts to exclude carriers whom they prefer to describe—and mythologize—as rugged-individualists and self-employed business boys and girls. By doing so, they have chiseled away protections that these workers should have.

Why have legislatures and courts been able to deprive child (and adult) carriers of the protections that most workers in other industries enjoy? The answer is surprisingly simple: The newspaper industry has been extraordinarily effective in perpetuating the myth of the “Little Merchant.” Publishers have made the public believe that distribution to subscribers is an entirely separate business dominated by prepubescent entrepreneurs going through a rite of passage, which the government should not regulate.

Using this same line of argument has also enabled publishers to escape child labor statutes. However, it is curious that the same people who define a 10-year-old as “an independent business person” do not hesitate to encroach on this entrepreneur’s independence by dictating to carriers rules under which they operate, as my local paper does: “If you collect from your customers, NEVER enter the home of someone who is not a personal friend of your family.”

This instruction—along with training videos that some papers provide to carriers—is obviously meant to protect the child. But publishers shouldn’t be allowed to have it both ways. The kind of verbal gymnastics that they use to get around these laws are an attempt to keep costs down while getting the job done. A 1988 article in Editor & Publisher framed the situation well and the author’s analysis holds up a decade later. Mark Fitzgerald wrote that the publishers’ stance illustrates their strategy to devise a “solution to the enduring newspaper circulation dilemma: the desire to control subscription lists, home delivery prices, and carrier performance standards while at the same time avoiding the taxes, salaries and benefits involved in actually employing the carriers.”

The rates that are charged for workers’ compensation insurance underscore the potential dangers of newspaper delivery work. In California, for example, an industrial accident insurance carrier charges $9.14 per $100 of payroll for this group, a rate that is considerably higher than rates for many manufacturing industries. Some newspapers do enable carriers to buy accident insurance at group rates and carriers must pay for it. Precisely because such insurance is optional, unlike workers’ compensation, many workers, given their low earnings, do not buy it. And workers’ compensation, unlike accident insurance policies, places no limit on coverage for medical treatment needed to cure or relieve the effects of work-related injuries. In some states—notably Wisconsin, Maryland, and Kentucky—workers’ compensation laws do cover all carriers, and in New York child carriers are included by statute. In contrast, in Arkansas, Montana, Oregon and Washington, publishers have persuaded state legislatures to exclude carriers from their laws, and in Georgia, Mississippi and North Dakota, the exclusion takes place merely because of the way publishers write their agreements with carriers.

Industry executives lobby policymakers by trying to convince them that this is a “bottom line” issue. Clyde Northrop, President of the American Association of Independent Newspaper Distributors, was quoted as saying that because profit margins are so thin “managers cannot be forced into operating an employee work force when heretofore it was independent contractors.” However, a 1993 study by Robert Picard, Professor of Communication at California State University at Fullerton, found that the industry “continues to be one of the most profitable.” Publicly traded newspaper companies, according to Editor & Publisher, yielded an average operating profit margin of 13.9 percent in 1993; by 1997 operating profit margins swelled to 20.2 percent. At newspapers where carriers are treated as employees, they perform up to publishers’ standards without sending owners into bankruptcy. The Wall Street Journal’s subsidiary, National Delivery Service, for example, provides workers’ compensation for its carriers, and in 1997 the paper “enjoyed a record year,” according to Editor & Publisher.

Only when these issues of child labor and workers’ compensation receive a fair hearing in the court of public opinion—a court that is largely controlled by information the media make available—are they likely to be resolved in ways that could ensure worker protections for newspaper carriers. Until then, many children’s first job experience will teach them an invaluable lesson: Some employers are chiselers.

Marc Linder is a law professor at the University of Iowa. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he represents migrant farm workers through Texas Rural Legal Aid and has written many books and articles on labor law and economic history.

The fate of 13-year-old Stephen Johnson, who was gravely injured by a car while delivering The Dubois (Penn.) Courier, illustrates the danger this job can entail and what can happen when accidents occur. Even though The Courier paid Stephen five cents for each paper he delivered and the subscribers wrote their checks to The Dubois Courier directly—which meant that Stephen handled no money—Pennsylvania’s appellate court held in 1993 that as a “self-employed businessman” Stephen was, as the paper argued in court, unprotected by workers’ compensation. The court’s legal finding rested on the assertion that the boy “was essentially acting as a delivery service such as UPS or Federal Express.”

An example of an ad newspapers commonly use to recruit carriers.

Children as Carriers: Working Without a Safety Net

Lack of workers’ compensation coverage means some injured carriers, including children, don’t receive the medical or rehabilitative treatment they need. In other cases, they or their parents confront large hospital bills that injured employees in other sectors never do because they are paid for by the industry and consumers.

The same year as Stephen’s lawsuit, a judge in another case rendered a very different opinion. In this case a 12-year-old girl was struck by a car while she was delivering The Fremont (Neb.) Tribune and put into a permanent vegetative state. This judge, who was the first to review the workers’ compensation claim, wrote (in regard to The Tribune’s policy of using young children to deliver papers): “It is beyond sophistry and closer to outright dishonesty to characterize a 10-year-old party to a contract as a ‘little merchant’ and thus an independent contractor.”

This judicial reasoning didn’t stop The Fremont Tribune from continuing to litigate this case, arguing that it should not be held responsible for the medical expenses related to this girl’s accident. The Tribune took the case up to the Nebraska Supreme Court, and three publishing associations and two newspapers supported its cause by submitting friends of the court briefs. And as the case worked its way through the courts, the Nebraska Press Association prevailed upon the state legislature three times to kill proposed amendments to the workers’ compensation statute to extend benefits to carriers.

Evidence in this court case showed that The Tribune told carriers when to deliver the paper, how to band and “porch” it, how to deal with customers who stopped subscribing, and prescribed collection methods and appearance standards. Despite this obvious control, the paper claimed that Larson and carriers as young as 10 were “merely subscribers of the newspaper” who happened to resell it. When I asked about this apparent contradiction, Mary Sepucha, Director of Employee Relations at the Newspaper Association of America, chanted the mantra that publishers have rehearsed for a century: “But they’re not our employees, they’re independent contractors, and we’re not responsible for them.” More brazen still was the response of Sandra George, Executive Director of the Wisconsin Newspaper Association: George justified The Tribune’s litigation by contending that the paper simply “had nothing to do with” Larson’s injury.

These kinds of self-exculpatory statements from newspaper publishers result from their decades-long, successful campaign to exclude newspaper carriers—even children—from coverage under their workers’ compensation plans. And members of the community are rarely brought face-to-face with these child labor issues because the parties with the most to gain by public ignorance—the newspapers—have the ability to control whether this news is considered fit to print. For example, when publishers contest workers’ compensation coverage for seriously injured child carriers, no public relations disaster results because those who read their newspaper rarely know that such a case is going on. Nor are most people likely to be aware that from 1992 to 1997, 99 news vendors were killed on the job, 11 of them under 18 years old. Non-fatal injury rates among the nation’s 405,000 carriers, nearly half of whom are youngsters, are not even tracked.

Workers’ Compensation: The Publishers’ Perspective

Workers’ compensation rests on the principle that job-related injuries represent part of the cost of production and distribution of products; employers insure workers against such economic losses and recoup the insurance cost from consumers. Since the turn of the century, the movement to ensure that employers provide workers’ compensation has highlighted the need for run-of-the-mill workers to have such coverage since they lack the ability to charge consumers directly for the cost of their job-related injuries. But newspaper publishers have also been working hard to persuade legislatures and courts to exclude carriers whom they prefer to describe—and mythologize—as rugged-individualists and self-employed business boys and girls. By doing so, they have chiseled away protections that these workers should have.

Why have legislatures and courts been able to deprive child (and adult) carriers of the protections that most workers in other industries enjoy? The answer is surprisingly simple: The newspaper industry has been extraordinarily effective in perpetuating the myth of the “Little Merchant.” Publishers have made the public believe that distribution to subscribers is an entirely separate business dominated by prepubescent entrepreneurs going through a rite of passage, which the government should not regulate.

Using this same line of argument has also enabled publishers to escape child labor statutes. However, it is curious that the same people who define a 10-year-old as “an independent business person” do not hesitate to encroach on this entrepreneur’s independence by dictating to carriers rules under which they operate, as my local paper does: “If you collect from your customers, NEVER enter the home of someone who is not a personal friend of your family.”

This instruction—along with training videos that some papers provide to carriers—is obviously meant to protect the child. But publishers shouldn’t be allowed to have it both ways. The kind of verbal gymnastics that they use to get around these laws are an attempt to keep costs down while getting the job done. A 1988 article in Editor & Publisher framed the situation well and the author’s analysis holds up a decade later. Mark Fitzgerald wrote that the publishers’ stance illustrates their strategy to devise a “solution to the enduring newspaper circulation dilemma: the desire to control subscription lists, home delivery prices, and carrier performance standards while at the same time avoiding the taxes, salaries and benefits involved in actually employing the carriers.”

The rates that are charged for workers’ compensation insurance underscore the potential dangers of newspaper delivery work. In California, for example, an industrial accident insurance carrier charges $9.14 per $100 of payroll for this group, a rate that is considerably higher than rates for many manufacturing industries. Some newspapers do enable carriers to buy accident insurance at group rates and carriers must pay for it. Precisely because such insurance is optional, unlike workers’ compensation, many workers, given their low earnings, do not buy it. And workers’ compensation, unlike accident insurance policies, places no limit on coverage for medical treatment needed to cure or relieve the effects of work-related injuries. In some states—notably Wisconsin, Maryland, and Kentucky—workers’ compensation laws do cover all carriers, and in New York child carriers are included by statute. In contrast, in Arkansas, Montana, Oregon and Washington, publishers have persuaded state legislatures to exclude carriers from their laws, and in Georgia, Mississippi and North Dakota, the exclusion takes place merely because of the way publishers write their agreements with carriers.

Industry executives lobby policymakers by trying to convince them that this is a “bottom line” issue. Clyde Northrop, President of the American Association of Independent Newspaper Distributors, was quoted as saying that because profit margins are so thin “managers cannot be forced into operating an employee work force when heretofore it was independent contractors.” However, a 1993 study by Robert Picard, Professor of Communication at California State University at Fullerton, found that the industry “continues to be one of the most profitable.” Publicly traded newspaper companies, according to Editor & Publisher, yielded an average operating profit margin of 13.9 percent in 1993; by 1997 operating profit margins swelled to 20.2 percent. At newspapers where carriers are treated as employees, they perform up to publishers’ standards without sending owners into bankruptcy. The Wall Street Journal’s subsidiary, National Delivery Service, for example, provides workers’ compensation for its carriers, and in 1997 the paper “enjoyed a record year,” according to Editor & Publisher.

Only when these issues of child labor and workers’ compensation receive a fair hearing in the court of public opinion—a court that is largely controlled by information the media make available—are they likely to be resolved in ways that could ensure worker protections for newspaper carriers. Until then, many children’s first job experience will teach them an invaluable lesson: Some employers are chiselers.

Marc Linder is a law professor at the University of Iowa. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he represents migrant farm workers through Texas Rural Legal Aid and has written many books and articles on labor law and economic history.