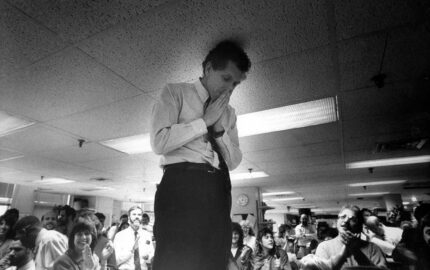

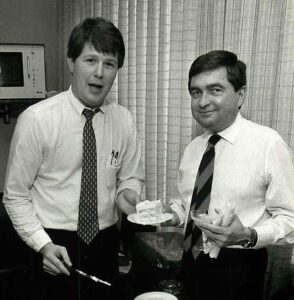

Rodrigue and Craig Flournoy won The Dallas Morning News’s first Pulitzer for their investigation into the racial discrimination and segregation pervading public housing in East Texas and across the country.

Despite federal laws prohibiting racial discrimination, the nearly 10 million residents of federally assisted housing are mostly segregated by race, with whites faring much better than blacks and Hispanics.

In a 14-month investigation of the country’s 60,000 federally subsidized rental developments, The Dallas Morning News visited 47 cities across the nation and found that virtually every predominantly white-occupied housing project was significantly superior in condition, location, services and amenities to developments that house mostly blacks and Hispanics.

The News did not find a single locality in which federal rent-subsidy housing was fully integrated or in which services and amenities were equal for whites and minority tenants living in separate projects.

...

In the blistering heat of Kern County, Calif., local public housing officials provide one overwhelmingly white-occupied project with central air conditioning and the other white project with new air coolers. Tenants at five of the seven predominantly minority projects and the one integrated project have neither.

In the southern Georgia community of McRae, the white project has a well-equipped playground, offstreet parking and paved streets. The black project has none of these amenities, and its tenants say the housing authority fails to make repairs. Leona Hurst, head of the McRae Housing Authority, said black tenants are responsible for most of the maintenance problems because “the blacks just don’t keep the property up.”

In Marshall, Mo., there are four white projects and one black project. On a snowy day in December 1983, housing authority Executive Director Jack McCord illegally tried to evict all the tenants in the black project. McCord said the eviction was necessary because the black tenants refused to tell him who was responsible for “vandalism, parties, harassments, breakins, etc.”

Although he later agreed to halt the eviction process, McCord said he is moving only white tenants into the black project instead of the “yahoos.” Said tenant leader Ylantha Erby of such treatment, “You feel like a dog, like you’re less than human.”

© 1986 The Dallas Morning News, Inc.