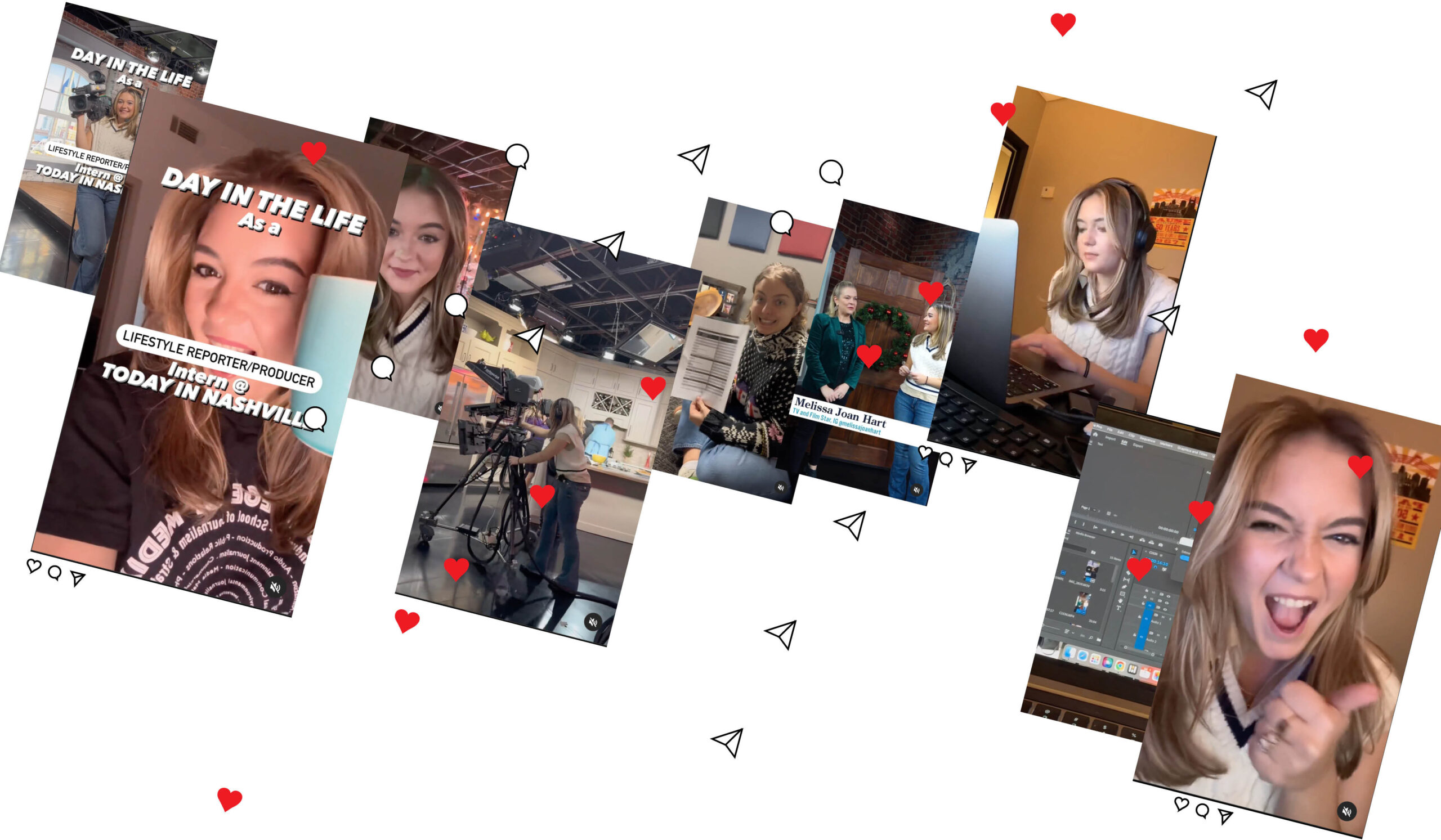

Part of Izzy Gutierrez’s job as an intern at Nashville TV station WSMV was to produce peppy Instagram reels about what happens behind the scenes at the station’s lifestyle show, Today in Nashville.

There was Gutierrez getting ready for work, sipping her coffee on the way, and arriving at the office. Gutierrez at a pre-show meeting, writing flash cards, and setting up the mics. Gutierrez holding a video camera, interviewing guests for the program’s Facebook page, writing segments for the following week’s episodes, and making more videos for other social media.

The Ohio native, who wants to be a lifestyle reporter, learned many of these skills at Middle Tennessee State University, where she is a journalism major scheduled to graduate in May.

Many employers have come to expect that journalists will know how to brand themselves on social media. “We want people who are more like influencers doing these jobs,” Gutierrez says employers tell her.

The influencer phenomenon is not only changing how information is delivered and consumed. It’s complicating the job of journalism schools that are trying to impart conventional journalism principles to aspiring journalists who grew up in the influencer era, and who see their roles in a different way than their predecessors might have.

To adapt, journalism education is now borrowing from such disciplines as marketing, public relations, and advertising.

“In a lot of ways, our students are marketing themselves,” says Amber Hinsley, an associate professor and program coordinator at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Texas State University and former city editor of two community sections of the Los Angeles Times. “They’re thinking of themselves as professional storytellers, and not necessarily professional journalists.”

To help them connect those roles, Hinsley has her students watch what working journalists are doing successfully on social media, such as showing themselves behind the scenes. “We try to bring in thoughtful ways of thinking about what is the message this journalist is telling.”

This is more than a minor adaptation, says Andrea Press, chair of media studies at the University of Virginia. “You have to cultivate different talents than you did before,” Press says. “What made you a good journalist in a prior era might be totally different from what makes you a good journalist in this one.”

When Matthew Taylor teaches his incoming journalist students at Middle Tennessee State, he finds he needs to explain what journalism is and why content needs to be solidly reported, rather than just a collection of clever takes designed to get likes.

“That has become very muddy for younger people” raised on social media slants on the news, says Taylor, an assistant professor in the university’s School of Journalism and Strategic Media, where he teaches a class in social media and sports. “In the past, it was more that students came in with an understanding of journalism and you were teaching them about such things as objectivity. We have to start at a more basic level now.”

But his department also is equipping students with the knowledge they need to stand out on social media. In addition to a core class in writing, students are required to take a class on digital media that covers how to create video, audio, photography, and other elements.

“In a lot of ways, our students are marketing themselves. They’re thinking of themselves as professional storytellers, and not necessarily professional journalists.”

— Amber Hinsley, associate professor and program coordinator at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Texas State University

An influencer is a person who transforms him or herself into a brand using social media and builds a relationship with an audience through a regular flow of content, says Robert Kozinets, professor of journalism at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. He coauthored a textbook on the subject and teaches a course at USC called “Influencer Relations,” which covers social media as a cultural phenomenon and an aspect of contemporary communication, rather than coaching future influencers about how to do it.

That definition of influencer describes a growing number of journalists who often center themselves in stories on social media.

Knowing how to do this “has become a necessary skill,” says Taylor. “At a very basic level, if you aren’t going to offer courses that get very deep into social media, you need to teach social media in a way that helps students operate responsibly in that space.” Half of Americans now get at least some of their news from social media, according to the Pew Research Center. The proportion who regularly get news on TikTok has more than quadrupled in the last three years to 14 percent, Pew says, while 16 percent get news on Instagram, and 12 percent on X.

A growing proportion of users tell Pew that they trust what they find on social media almost as much as what they read, watch, or hear on conventional local and national news outlets.

Journalism schools are adapting to this reality. In addition to Kozinets’s class, USC’s Annenberg School offers entire master’s degrees in digital social media and digital media management. At Columbia Journalism School, a course in investigative techniques now covers how to use social media for reporting. Northwestern’s Medill School offers classes in social media marketing that can be bundled together into a certificate.

And showing young journalists how to live up to the trust news consumers say they have in social media has become a principal focus of many college-level journalism courses.

It’s one thing to be an influencer, but another to be a journalist who is an influencer, says Vicki Michaelis, director of the Carmical Sports Media Institute at the University of Georgia, which offers a certificate program in social and digital media production for sports.

To aspiring journalists, “the influencer is the person from whom they’ve gotten information,” Michaelis says. That sometimes skews how they understand journalism, she says, since influencers often win followers by having distinctive — and often inflammatory — points of view.

“We’ve always talked about voice in journalism, and when you talk about voice to students who come into J-school these days, they think you’re referring to their opinion,” says Michaelis, who covered sports for 21 years for USA Today, The Denver Post, and other outlets. “They’re used to ranting and raving and people presenting just really strong, direct opinions” on the social media they’ve grown up with.

She says she spends much of her time steering her students away from this approach. Still, journalistic objectivity “is a very hard thing to teach,” Michaelis says, noting it doesn’t necessarily mean giving both sides equal weight if they don’t deserve it and that “we bring our own experiences” to every situation. “Most of it is anchored to credibility, and that’s a really amorphous concept for them to understand. What I tell them is, their credibility is the most valuable thing they carry into this profession” — and into cyberspace.

To make that stick, Michaelis says, she takes a practical approach: She reminds her students that employers want to hire human beings who can report facts and tell compelling stories, not give unsubstantiated opinions or recite inconsequential information that often fuels social media. “I start every class with, ‘Look if you’re just here to give me a sports score, I’m sorry — you’ll be out of a job. AI can do that.’”

This takes some adjustment, says Regina Clark, an associate professor of journalism at Ramapo College in New Jersey who teaches a course in writing for social media.

“My goal with students is to get them to think differently about how they communicate in terms of accuracy of information, paying attention to what they’re liking and sharing,” Clark says. Since most, if not all, of her students are already on social media, “I show them how to use it in a more accurate way.”

She does this by spending a lot of time discussing sourcing and how to identify fake news. Clark also asks each of her students to create a blog, a format more text-heavy than other kinds of digital media.

“We’re looking at it from a more professional space as newsgathering,” she says. “We’re not looking at it as your own personal Instagram or Snapchat. I make sure it’s clear on the syllabus that you’re going to have to do more than write tweets.” Students in the journalism concentration are required to have internships, too; if they expect that selfies with celebrities will satisfy employers, that experience will likely set them straight, Clark says.

Kozinets, at USC, says the angst around how journalists should act in cyberspace is as old as when the internet democratized access to wide audiences. “Part of this is the old game of the older generation trying to figure out what the younger generation is up to,” he says.

“When you ask someone who’s in a journalism program whether influencers can be legitimate guardians of the values of the press, they’re probably going to think of someone dancing around on TikTok,” Kozinets says. “But we’re into a radical redefinition of what news is. There’s a lot of entertainment mixed into the news. There’s a lot of celebrification of the newscaster.”

As for readers, viewers, listeners, and scrollers, “I don’t think they care whether someone is a professional journalist,” he says. “If people were to choose, they would probably choose to watch someone on the ground in Gaza who lives there reporting on what just happened in their neighborhood [rather] than hear from someone from behind a desk and filtering it.”

Press, the media studies chair, agrees that influencer culture is vastly changing journalism. “If you compare this to the climate for working journalists before the age of social media, I don’t think you can get any starker contrast,” she says.

“You have to be entertaining. That’s the priority. If you don’t happen to have that talent — which not every journalist used to have — then you’re not going to necessarily succeed.”

“We’re into a radical redefinition of what news is. There’s a lot of entertainment mixed into the news. There’s a lot of celebrification of the newscaster.”

— Robert Kozinets, professor of journalism at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Journalism faculty who teach social media are also confronting a broader historical misunderstanding of its role by journalists in general, Michaelis says.

“When the internet came to be, [journalism] companies mistakenly thought that the internet was a way to direct the audience back to their newspapers,” she says. “They realized seven or eight years ago that they were making the same mistake about social media, when in fact the journalism needs to be contained within the social media, because that’s how the audience consumes it.”

Journalism students are newly demanding something else, too: more information about how to safely create the kind of content influencers do.

“One of the topics that’s gotten the most interest is when I talk about media law and, in particular, copyright,” says Hinsley. “I frame it as students thinking of themselves as content creators. They ask good questions about when is it okay to use certain images or music, and about protecting themselves from issues of violating copyright. That’s the world that students see themselves living in now, personally as well as professionally.”

Bryant Kwilecki, a journalism major at the University of South Alabama who will also graduate in May and hopes to be an on-camera sports reporter, made sure to take a course in social media and uses what he learned to produce a football podcast he cohosts on YouTube.

“You have to be different. You have to stand out from your competitors,” Kwilecki says. “You have to learn how to be — I don’t want to say clickbait, but you need to draw in those listeners, get those views, and target the audience you want.”

Journalism faculty who teach social media courses report that they are typically among the first to fill. At Ramapo, Clark’s classes often have waitlists.

“For better or for worse, we are definitely moving to a point where a journalist must consider bolstering their brand,” says George Bovenizer, who spent 27 years as a broadcast journalist and last worked at NBCUniversal in Los Angeles. He is now an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of South Alabama, where he teaches a course in social media. “I do think journalists need to take some marketing lessons from influencers in order to stay relevant to a wider audience that is decreasingly watching linear news programs.”

The momentum of the influencer train may be long past stopping. But young journalists appear responsive to learning these kinds of skills before they jump aboard.

Before South Alabama senior Luke Vailes took Bovenizer’s class, he says, he was already on social media almost every day. “My brain was hard-wired to see the subjective things that are on there and the random people and not necessarily the objective truth,” he says. Taking the course “changed the algorithm around for me. I’ll get more thought-out things now, things from actual news stations, news websites.”

Rather than fear the transformation of journalists into influencers, says USC’s Kozinets, it’s time to acknowledge that the delivery of news is simply changing yet again.

People who despair for traditional journalism “are really desperately clinging to legitimacy because they think the ship is sinking,” he says. “But I don’t think the ship is sinking. There are just going to be a lot of little life rafts.”