Picture a world where evidence doesn't matter, where the loudest voices win, and where calling out falsehoods is seen as an act of bias. Welcome to 2025.

Donald Trump — the most fact-checked presidential candidate in history, because he’s spoken the most falsehoods — won the White House again. The social media company Meta, which owns Facebook, ended its third-party fact-checking program, with CEO Mark Zuckerberg claiming that fact-checkers are biased. Partisan podcasters and viral video snippets command attention, while the business models for longform journalism struggle. Public trust in news in the United States is at an all-time low, with growing news avoidance and declining page views.

If history has its eyes on journalism, it feels like a death stare. I know, because I've spent my career on journalism's fact-checking front lines — first as a journalist with PolitiFact since its founding in 2007, then as its editor-in-chief through three presidential administrations. Today, as director of the International Fact-Checking Network, I work with journalists around the world to promote high standards of accuracy.

I’ve been hearing more disillusionment lately, with fact-checking specifically and nonpartisan journalism in general: It’s not strong enough, it’s not confrontational enough, it just doesn’t “work.”

But fact-checking does work — just differently from how its critics suppose. The same is true of any type of fact-centered independent journalism.

Here’s how it does not work: Fact-checking can’t prevent individual politicians from winning or losing elections. It doesn’t knock on doors or get out the vote. It’s not persuasive to people who vote based on their cultural values or their pocketbooks. It doesn’t do the work that opposition parties and political movements are supposed to.

What fact-checking does do, and what it does well, is resist false narratives and prevent them from becoming entrenched. It holds the line on reality for history’s sake. It builds evidence-based records that can withstand political pressures. That’s why the politicians who seek to create their own realities are fighting so hard against fact-checking, and why they are now strong-arming tech companies and social media platforms into aiding them.

In my years of fact-checking, I've seen how this methodical gathering of evidence is journalism’s strongest defense against those who would invent and falsify claims for their own ends. Journalists working under repressive governments around the world understand this instinctively: Fact-checking isn't just about correcting the record; it's about preserving reality itself.

What fact-checking does do, and what it does well, is resist false narratives and prevent them from becoming entrenched. It holds the line on reality for history’s sake.

This rigorous fidelity to facts — to gathering evidence before reaching conclusions — is the true meaning of objectivity in journalism. It's not about being neutral or passive, but about being relentlessly committed to uncovering what's true and accurate. When democracy is under threat, this disciplined approach to truth-seeking becomes more crucial than ever. It's what distinguishes journalism from content production or social media commentary. We follow the evidence wherever it leads, even when it challenges our own assumptions.

Remembering journalism’s history

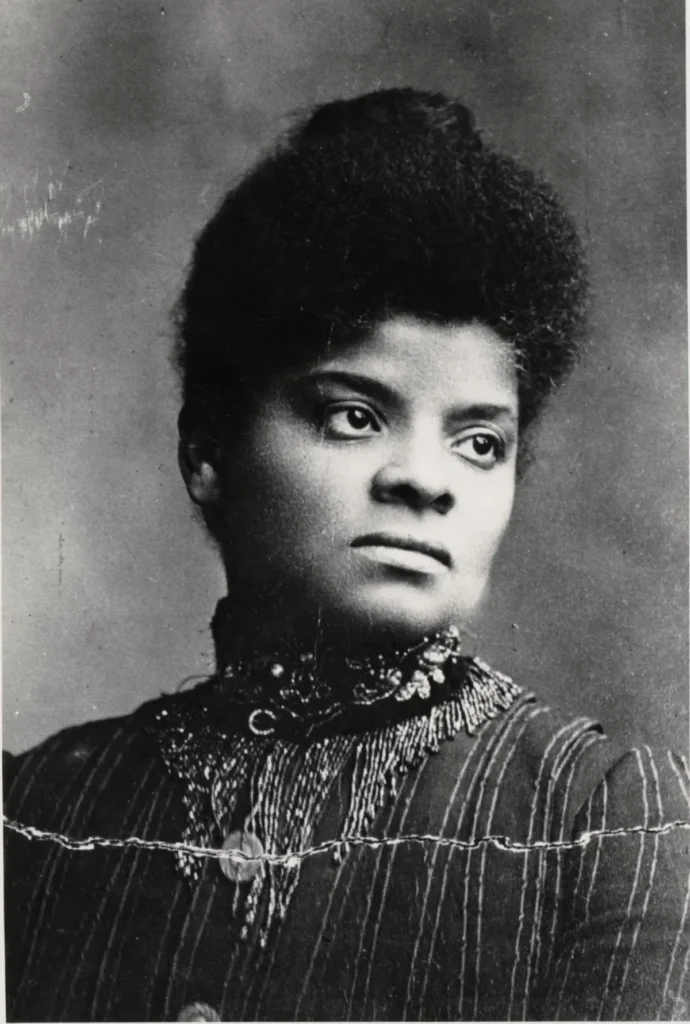

As I've thought about how to maintain rigorous fact-checking in today’s charged environment, I keep coming back to journalists who've faced even tougher times. No one inspires me more than Ida B. Wells. In an era when false narratives justified horrific violence, Wells showed how meticulous fact-gathering could expose lies and challenge power.

A self-described crusader against lynching in the post-Civil War era, Wells approached her reporting by vigorously checking the facts of newspapers and law enforcement that were explicitly white supremacist. Her 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases” showed the injustice of lynching by digging deep into the particulars of case after case throughout the South.

Her reporting focused on false claims of Black men raping white women. More often than not, she found, these were cases of consensual interracial relationships that became known and that then triggered mob violence. Wells analyzed the dynamics of Southern whites trying to maintain political power after losing the Civil War, and she looked at how Black communities were torn over whether to challenge white power or accommodate themselves to it. She included factual points that didn’t perfectly support her arguments as a way to show she had fully and fairly considered the views of her opponents. Her moral arguments often centered on universal standards concerning the rule of law and civil rights that she argued should apply to all citizens.

Wells also argued that journalists’ first duty was to place true facts before the public. “The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press,” she wrote. She called on Black-owned newspapers to collaborate in hiring detectives to investigate individual lynchings across the country and then to collectively publish the evidence, countering “every garbled and slanderous dispatch” with truthful journalism.

Wells stands in sharp contrast to other historical examples of journalists who didn’t stay focused on accuracy — and who therefore made errors and were easily manipulated. In “A Test of the News,” published in 1920, Walter Lippmann and Charles Merz analyzed The New York Times' reporting of the 1917 Russian Revolution. By examining hundreds of hard news reports from the Times’ pages, they showed that the coverage repeatedly and misleadingly suggested the Bolsheviks were about to lose power and Russia would continue to fight in World War I alongside the Allied Powers. Neither of those things happened. “A Test of the News” demonstrates what happens when the press takes a side and starts putting out stories before all the facts are in. “In the large, the news about Russia is a case of seeing not what was, but what men wished to see,” Lippmann and Merz concluded.

The Times’ reporters had relied too heavily on government officials and anonymous sources to confirm their own ideas instead of investigating evidence to the contrary. The same thing happened during the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War, when the Times’ most prominent coverage credulously repeated the claims that President George W. Bush used to justify an invasion of Iraq. Rather than staying open to evidence that Iraq didn’t possess weapons of mass destruction, the Times’ reporting took the government’s claims at face value.

In 2024, when considering the coverage of Trump’s campaign to recapture the White House, it’s worth asking whether many journalists felt personally reluctant to recognize Trump's enduring appeal, leading them to underreport on what ultimately led to his decisive victory over Kamala Harris — similar to how, in 2016, little reporting suggested he could achieve an electoral college victory over Hillary Clinton.

This gets to the heart of the problem of journalists who aren’t willing to set their own political views aside, no matter how well-intentioned they may be. Because of human psychology and confirmation bias, hewing to an agenda or a political ideology can cause journalists to cut corners and overlook evidence that shows the world not as it is but how they wish it to be. This leads to shallow coverage that can’t stand on its own during chaotic historical moments. But when journalists maintain their rigor, when they put facts first and follow where the evidence leads, the press has real power.

That power lies in its ability to assemble convincing records of evidence that expose and resist alternative narratives. Combining a moral compass with systematic evidence-gathering is never more important than when democratic freedoms are under threat from would-be dictators and oligarchs.

When autocrats seek unlimited power, their first move is often to control information by stifling the independent press. (Their other primary target is an independent judiciary.) Trump exemplifies this through both his actions and his threats — filing frequent defamation lawsuits against news organizations, calling journalists "enemies of the people," and vowing to use his power against critics in the media.

These attacks make it tempting to see Trump as an adversary, but that is the domain of columnists and First Amendment lawyers. Reporters need to focus on defending their independence and rigorous reporting methods – methods that are at the core of the modern fact-checking movement. When I train fact-checkers, I tell them to examine claims as if they were likely false and look for contradictory evidence, and then to examine those same claims as if they might be true and look for supporting evidence. Ideally, the method brings equal rigor to verification and debunking. I tell reporters to document their research and show their work. One of the hallmarks of modern fact-checking is extensive sourcing to establish evidence.

One of the best recent examples of fact-checking pushing back against a false narrative can be found in journalism about the 2020 election. While Trump has repeatedly said that the election was stolen from him by Joe Biden, an extensive factual record disproves that, and Trump’s claim is almost always contradicted in news reports that quote him or his supporters reiterating it. This is a tremendous accomplishment of a truth-seeking press, and it shows how trails of evidence can disrupt politicians’ attempts to control information. Journalism creates a space for the public to think critically.

Being genuinely open-minded and considering all evidence is critical to journalism’s power, says Larry Diamond, a political scientist at Stanford University who has studied democracy around the world and advised policymakers and activists on how to preserve it.

Diamond says the press needs to have courage in the face of threats, but it also needs to report and analyze impartially.

“It's a huge mistake for the independent press to play into the hands of a populist authoritarian project by thinking that they need to wage a political battle against the administration, that they need to be the spearhead of it,” Diamond told me. “They can report on what others are saying and doing. But journalism itself cannot descend into being a political project of the government, for or against it. And if journalists think they're defending freedom in that way, they're not.”

Journalists also need to make the case that, while many of the claims they examine are political, their work is not political or partisan in and of itself.

"If nobody is pointing out what's true and what's false, it affects your welfare and safety. It's not about partisanship,” said Gemma Mendoza. She’s lead researcher for disinformation at Rappler, the Philippines-based website founded by Nobel Prize-winner Maria Ressa.

I asked Mendoza how Rappler covered the news during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, who was very Trump-like in his vilification of the press, his willingness to traffic in false narratives, and his undermining of democratic institutions.

“We cannot be apologizing for fact-checking our leaders. We still need to do it. But it goes side by side with everything else,” she said. That includes reporting on scams, investigative journalism, and analyzing overarching false narratives. “What we have been trying to explain to our audiences is that all of this affects your welfare.”

Meeting the moment

As a fact-checker, I’ve watched our careful methods compete with an entirely different way of embracing and sharing information. While we meticulously gather evidence, viral videos and marathon podcasts grab attention and are hailed as the media of the future.

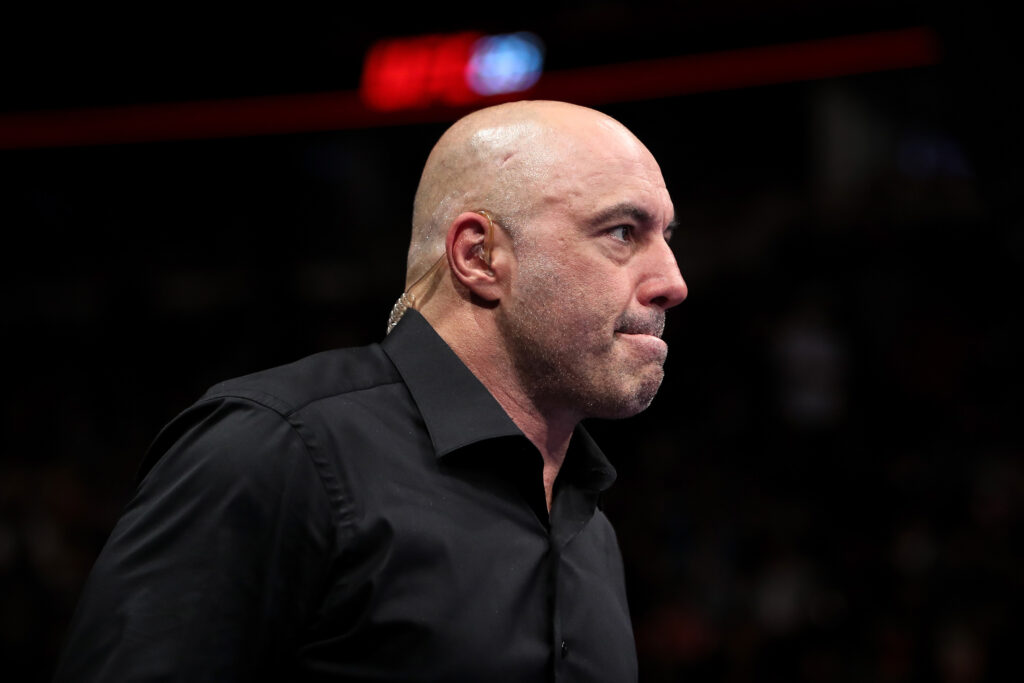

Many political analysts credited Trump’s win to his social media performance and his appearance on the Joe Rogan podcast. An analysis by Bloomberg News of a small cohort of conservative-leaning podcasters suggested that many young men swung from Biden in 2020 to Trump in 2024. The reason? Political messaging was integrated into podcasts that once focused on sports, masculinity, and internet culture.

Rogan's hours-long conversations create an impression of substantive discussion, but it’s misleading. There’s none of the critical questioning and real-time fact-checking that journalism requires. Walter Lippmann would likely recognize Rogan as just the sort of public relations man he warned against 100 years ago. Writing in "The Phantom Public," Lippmann noted that people had short attention spans and a tremendous desire to be entertained: "The public will arrive in the middle of the third act and will leave before the last curtain, having stayed just long enough perhaps to decide who is the hero and who the villain of the piece.”

Media theorist Neil Postman detected the same tendency in the 1980s when his book “Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business" was published. Rather than Trump and Rogan, Postman saw the dynamic at work between President Ronald Reagan and television news. Americans, Postman wrote, "no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas; they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials."

If journalism is trying to beat entertainment at the attention game, we are not likely to win. Entertainment narratives are free to deal in stereotypes and caricatures of heroes and villains, whereas journalism must grapple with complexity, nuance and evidence. Journalists don’t know what they’ll find until they find it, and what they often find are facts that are contradictory or even mundane.

That might not make for high drama, but portraying the world accurately lies at the heart of journalism. Yes, journalism needs to be compelling and worthy of people’s time, but if we make entertainment our primary goal, we’ll be abandoning the evidence-gathering that defines us, and we won’t be doing journalism at all.

Right now, journalism is struggling in the attention marketplace, along with a host of other challenges. We need to shore up our legal defenses as we face more lawsuits and threats of lawsuits from Trump and his supporters. We need to look for new business models and philanthropy to sustain our work. We need to collaborate more among ourselves for greater impact and reach. We need to be more forthright in making our case that journalism matters, that it holds the powerful to account, that it promotes the common good. And we need not to expect the public to shower us with praise when we make that case.

Journalists working under repressive governments around the world understand this instinctively: Fact-checking isn't just about correcting the record; it's about preserving reality itself.

It's no accident that the historian and sociologist Michael Schudson wrote an entire book titled “Why Democracies Need an Unlovable Press.” We journalists can be highly unlovable — annoying, arrogant, muddled in our thinking, and going off on pointless tangents. But we can also be diligent, service-minded, helpful, and even noble. We tend to get better with practice, when we learn from our mistakes and when we try new formats to communicate even better.

“Fallibility is our middle name,” Schudson wrote. “But the conscientious effort to ascertain the facts and to get the story right and to stand tall rather than bow to hucksters on our doorsteps or high officials who seek our dollars or our votes or simply our submission — those conscientious efforts make a difference.”

As we enter the second Trump administration, I'm bracing for challenges but also feeling hopeful. We have the chance to look closely again at what role journalists play in a society where democracy, rule of law, and civil rights hang in the balance. My view is that journalism must resist becoming a political project either for or against government. The key is to preserve and defend our independence and professional standards while also acknowledging the moral stakes — doing our job without fear or favor and letting the evidence lead where it may. The opening events of 2025 are a test of the news and a test of our core values, not a reason to abandon them. History will be our ultimate judge, and if we do our best to pursue truth, history will judge us well.

Angie Drobnic Holan, a 2023 Nieman Fellow, is the director of the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute.