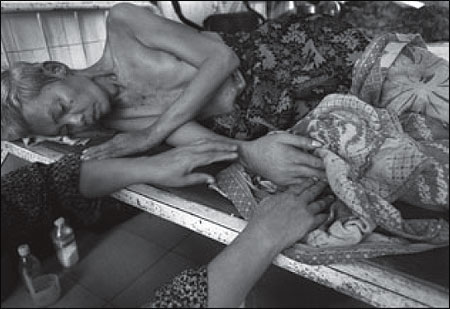

Kin Tem, 53, was a driver for a humanitarian organization before he died at the National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control in Phnom Penh of tuberculosis a few days after this photo was taken. His wife took care of him in the hospital. In Cambodia, tuberculosis infection rates are believed to be the highest in the world, according to the World Health Organization. Photo by Michele McDonald.

In mid-2002, development economist Jeffrey Sachs, then at Harvard University, presented a challenge to The Boston Globe’s foreign affairs correspondent, John Donnelly. Sachs had just led a World Health Organization (WHO) study that concluded that 8.8 million deaths could be prevented each year with basic health care. “Why weren’t the media reporting such a disaster?” Sachs asked.

Donnelly, who has reported for years on world health issues, recalls that at first he shrugged off the notion as naive: These deaths weren’t news, they were simply part of the grinding daily misery in poor countries around the world. After all, no newspaper would publish a headline saying thousands of people died needlessly yesterday.

But then Donnelly began to wonder: Could he make these deaths real for readers? Could a newspaper transform the WHO’s numbing statistics into words, photographs and graphics that would focus the thoughts and emotions of Americans on this distant suffering? Could such an effort make a difference?

Donnelly and veteran Globe photographer Dominic Chavez planned to travel first to Malawi in southern Africa, a country ravaged by AIDS and other diseases. The idea was to produce a major article on all the needless deaths that occurred on a given day. The Globe’s editor, Martin Baron, and executive editor Helen Donovan wondered aloud at a meeting in September: “Why just Africa? Why not worldwide?”

The undertaking grew quickly: In late October, the Globe dispatched four teams of reporters and photographers to distant corners of the world to see how lives were being lost due to the lack of basic health services. The goal was to learn who these dying people were, what their deaths meant to their families and their communities, and to look for ways similar deaths might be prevented.

The material the reporters and photographers brought back was so powerful that the project became still more ambitious—a 16-page special section, in full color. And this special section’s publication signaled the start of a yearlong occasional series on this topic. The story’s print version, which appeared January 26th, was mirrored by a sophisticated Web version on Boston.com.

The strength of the “Lives Lost” project is that it avoids the pitfall of predictability. The people’s stories are as distinct as the countries they come from: 37-year-old Nikolai Bogdanov failing to take his tuberculosis medication in Russia; one-year-old Franklin Veliz dying of pneumonia in Guatemala for lack of a simple vaccine; a 27- year-old mother, Sath Yan, dying in childbirth in a Cambodian jungle village because her family couldn’t find $15 to get her to a hospital, and a dying 16-year-old Malawian boy, Nenani Lungu, who whispers: “I see angels when I close my eyes.”

The Globe’s headline for this special section: “None of them had to die.” Below, in bold type, the story began: “Yesterday, 24,000 people worldwide could have been saved with basic care.”

A pond contaminated by manure from the surrounding rice fields, and by human waste during flooding, serves as the only water source for seven families in the village of Tropeang Khha, in western Cambodia.

A Cambodian family travels by motorbike with an IV hookup. Eighty percent of Cambodians lack access to proper medical care.

Hang Por tries to revive his wife, Ly Chanthon, 26, who later died of tuberculosis in Phnom Penh’s National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control.

Meas Rom, 36, a former soldier, lies dying from advanced stage tuberculosis. His mother, 55-year-old Chun Em, exhausted her meager savings to bring him to the National Center for what proved to be a futile attempt to treat him.

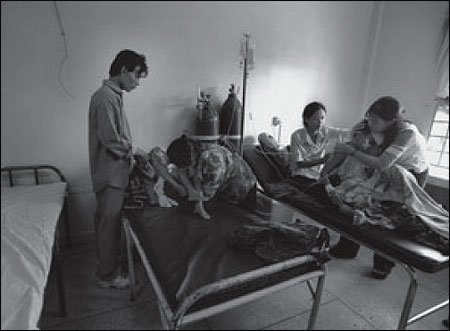

In a room doctors called an “intensive care unit,” a child, left, was seriously ill with typhoid fever. On the right, an older boy is being taken care of by his family. Photos by Michele McDonald.

James F. Smith is the foreign editor of The Boston Globe. Photos by Michele McDonald, a 1988 Nieman Fellow, who is a staff photographer for The Boston Globe.