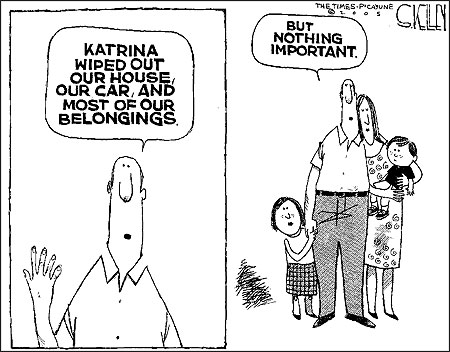

© 2005 Steve Kelley. Reproduced by permission.

My girlfriend called it “survivor’s guilt.” The stress—the anxiety tormenting my sleep at night and by day squeezing the throat of my creative process—was in fact a perverse remorse, a sense of regret that I hadn’t suffered Hurricane Katrina’s onslaught alongside my friends and colleagues at The Times-Picayune in New Orleans. Maybe she was onto something. As I read accounts of the newspaper staff’s persistent heroics in the face of all that Mother Nature and wholesale government incompetence conspired to produce, I wondered if I should be there, too, drawing cartoons about the disaster from ground zero instead of half a continent away. I could not shake the feeling that somehow, even if inadvertently, I had abandoned my post.

Five days before the storm struck, I’d flown to San Diego to host a comedy benefit for the Thousand Smiles Foundation, an alliance of oral and cosmetic surgeons who volunteer their time and skills for children in Mexico and Costa Rica. I closely monitored Katrina’s determined path across the Gulf of Mexico, a curved trajectory that rolled toward our coastline like an enormous bowling ball. As landfall neared, computer models projected that New Orleans would be its headpin.

U.S. Airways left a phone message to say it was canceling my flight home because of the hurricane. I felt anxious because I hadn’t prepared my house for the storm, yet somewhat relieved, as evacuating New Orleans on Sunday would have meant confronting 150 mile per hour winds in my 1970 two-seater. Anticipating a stay in San Diego of several days, I began mentally to organize. I would dismiss further thought about my house, the fate of which I could not influence, and concentrate my hopes on the people of New Orleans and on providing the best work I could for my newspaper.

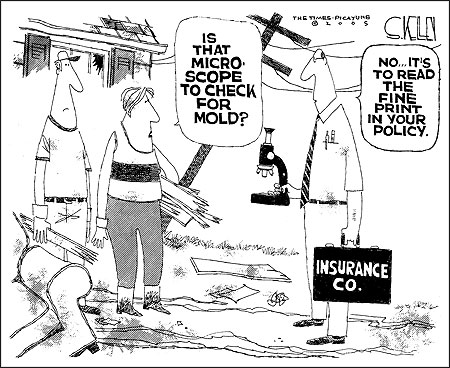

© 2005 Steve Kelley. Reproduced by permission.

Constraints of Tragedy

Nothing—and I mean nothing—is more difficult to address in a political cartoon than the deadly duo of tragedy and despair. Calamitous events demand comment, yet defy the kind of treatment—sarcasm, cynicism, pies in the face—that cartoonists usually administer. There is simply a limit to how many times a cartoonist can draw Uncle Sam, hat in hand and his head bowed, and I had succumbed to that image most recently when Ronald Reagan died.

So it was with acute trepidation that on the day after Katrina made landfall, I called my editor to see what direction she wanted my cartoons to take. She confirmed my darkest fears. For the next several weeks, I should confine myself to cartoons about the hurricane, and the tone must be “appropriate.”

Dear God, no—anything but appropriate.

Understand that for a quarter century of commenting on the news, one of my goals has been to amuse people. I’ve established an unspoken covenant with readers: They look at what I produce each day, and I provide something insightful and humorous or, at the very least, ironic about the world around them—in short, something worth their trouble. What I’ve labored assiduously to avoid is any sense of “appropriateness,” which to a political cartoonist is about as appealing as a game of chess might be to a Hell’s Angel.

Worse than the restrictions on tone, I knew that addressing a single, depressing topic every day would lead to stagnation and paralysis. It was as though the editors had put me in a tiny room with only one building block and asked me to construct something new and compelling five times a week.

So although I covered Hurricane Katrina and her aftermath from a safe and pleasant location, I will forever look back on that time in San Diego the way a grizzled, despondent war veteran with a vacant stare might recall time in a dank, filthy trench under fire. Years from now at our cartoonists’ convention, I’ll tell and retell how for six weeks back in the fall of ’05 I did nothing but hurricane cartoons, one right after the other. Everyone, especially the young guys, will gasp wide-eyed and plead to know, “Damn it, man, how did you do it?”

Like much of the world, and the rest of the country’s cartoonists, I watched our nation’s worst natural disaster unfold on CNN and Fox News. People would ask how I could draw cartoons about a story from so far away. The answer is that political cartoonists, like opinion columnists, don’t report the news, we tailgate it—offering commentary on events only after readers have absorbed the basic reporting from a variety of sources. This degree of separation offers certain advantages, much as watching a sporting event on television does. Multiple camera angles, running commentary, and especially specific, repeated broadcast images imprint on a cartoonist’s brain and oil the gears of his creativity.

© 2005 Steve Kelley. Reproduced by permission.

Searching for Ideas

On the Monday that Katrina plowed into New Orleans I sat, heart racing, before a computer terminal at a San Diego Kinko’s alternating among the Web sites of CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, and NOLA, my newspaper’s site. The early morning hours I spent watching CNN’s Anderson Cooper vaporized without ink touching paper, and as the clock ticked and my fourth espresso-laced beverage grew cold, a clammy panic set in.

Journalists long for grand-scale events, but the enormity of the Katrina story seemed to work against me. Cartoon ideas presented themselves, but none embraced the gravity of the situation. It wouldn’t be enough to say hurricanes are bad or to entreat the country to feel sorry for the victims. As the cartoonist of record in New Orleans, the city whose fate everyone was suddenly intent upon, what I produced that day might actually matter. Though I knew the paper’s readers had greater concerns, I felt responsible somehow to speak for them in what was surely their most grievous period of need.

Still, there I sat, comprehending all of it, and nowhere close to a viable idea.

I began to wonder if this was it—the choking point I always dreaded. In the midst of the most compelling news story I’d ever had to address, taking place in my own city, was I going to come up empty? For all of my effort, I had nothing to show anyone but half a dozen wads of crumpled paper and a sharply elevated pulse.

It is axiomatic that deadlines compel results and, with only 90 minutes left to draw, the muse arrived. My first cartoon in the storm’s wake would be of a man looking out and saying that Katrina had destroyed his home, his car, and most of his belongings. In the next frame, he hugs his wife and children and continues, “But nothing important.”

I attached the cartoon to an e-mail addressed to our photo department, hit send, and felt a simultaneous, precipitous decline in my blood pressure, a moment of misty tranquility that would evaporate as I confronted the awful and the obvious: What would I do tomorrow? It was as though I had just crossed the finish line of a marathon only to see a guy with a stopwatch, pointing a pistol in the air and saying, “On your mark ….”

In the days that followed, I came to realize that the hurricane was not a single event. Initial stories of the storm’s ferocity gave way to reports of levee breaks, flooded homes, and epic incompetence by government at every level, all begging for comment. Even before credible assessments of Katrina’s damage could be tolled, Hurricane Rita tore across the Gulf and thrashed southwest Louisiana and areas of Texas, reflooding parts of New Orleans and terrorizing tens of thousands of Katrina evacuees anew.

I drew a towering Mother Nature, rolling pin in hand, a few steps behind two nervous Katrina evacuees on a Houston street. One evacuee remarks, “I think we’re being followed.” Days later, I depicted an enormous woman, “RITA,” pulling a welcome mat from beneath a man labeled “Returning Evacuees.” Another cartoon noted the irony of the New Orleans Saints’ 2005 marketing slogan. A man standing amid the ruins of his home points to the words on his shirt, “You Gotta Have Faith,” and says, “Guess it’s not just the Saints slogan anymore.”

Despite presidential admonitions against playing the blame game, incompetents needed outing, and I was all too eager to help. I drew a cartoon entitled “Forced Evacuations We’d Like to See,” showing FEMA director Michael Brown and Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff being loaded onto a departing bus. I happily put a knee in the groin of insurance adjusters who were busily informing policyholders that homeowners insurance, which protects against loss from hurricanes, does not cover damage from rising water, a distinction understandably lost on the thousands of newly homeless.

On October 10th I returned, along with most of the newspaper’s staff, to our New Orleans offices. We remain fixated, like the rest of the city, on what the hurricanes did and where all of it will lead. Everyone is eager for a measure of normalcy to return and, to that end, I am trying to infuse my work with humor. Finally, funny feels appropriate again.

Driving across New Orleans since the storms, regardless of the route people take, they now encounter spectacular visual incongruities created by the storms that after several weeks have begun to seem routine. To a cartoonist, they’re irresistible. All I had to do was contrive a situation to list them. So I drew a mother saying to her daughter, “Yes, sweetheart, things are different since Katrina.” Across the living room, Dad is on the phone, giving directions: “Make a right at the second boat in the road, then a left at the overturned pick-up—our driveway is the fourth refrigerator on the right.”

And as Halloween approached, I drew three children at a doorstep, explaining their costumes to the home’s resident. “I’m a monster,” shouts the first, who is dressed as Frankenstein. “I’m a witch,” declares a little girl in a black dress and pointed hat. The third, a boy wearing a sports jacket and tie, says, “I’m a weatherman.” The home’s mortified owner recoils in fear, “Aaagh!! A weatherman!”

© 2005 Steve Kelley. Reproduced by permission.

© 2005 Steve Kelley. Reproduced by permission.

Steve Kelley is editorial cartoonist with The Times-Picayune in New Orleans. His work has won numerous awards, including the National Headliner Award in 2001.