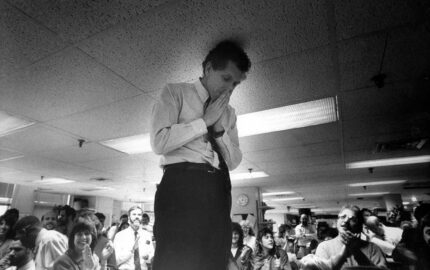

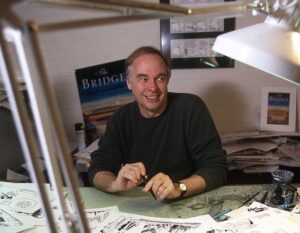

Marlette, who died in 2007, is remembered by Christopher Weyant, NF ’16, a cartoonist for The New Yorker.

Of the thousands of political cartoons I’ve read over the course of my career, one of the very best belongs to the brilliant Doug Marlette. When Pope John Paul II rejected the idea of allowing women to serve as priests in the Catholic Church, Marlette drew a cartoon of the Pope with his prominent forehead exaggerated for comic effect. An arrow points to his head and the caption, echoing Jesus’ words to St. Peter, reads, “Upon this rock I will build my church.”

This was Marlette at his best. Popes. Presidents. Congressmen. Evangelical preachers. The Supreme Court. No one with power could avoid the sharp end of Doug Marlette’s pen. He skewered the corrupt and the unjust, no matter who they were or how sacrosanct the issue.

Marlette, born and raised in North Carolina, hated hypocrisy in all its forms and never wasted an opportunity to expose it. Effortlessly, he distilled complex issues to their core and, when combined with his inventive visual imagery, would create a cartoon whose impact you would not soon forget. His bold line had an unusual openness about it, inviting the reader in before delivering its punch.

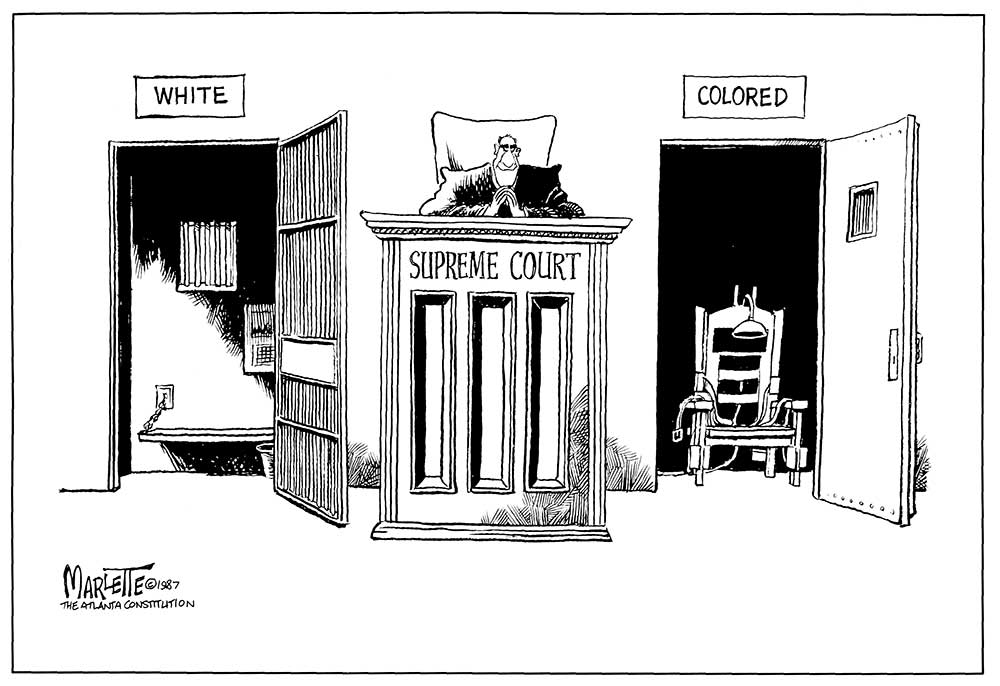

And that punch could be deadly. A cartoon from his 1988 Pulitzer Prize-winning selection depicted a Supreme Court justice seated at the bench. On either side of the bench are two doors. To the left, we see a jail cell with a sign above that reads “White.” To the right, an open execution chamber, complete with electric chair and a sign that says “Colored.” As powerful and relevant today as it was when it was when it was first published—this is an example of a master of his craft.

During my year as a Nieman Fellow, I have thought of him often, of his extraordinary talent, his wit, and his fearlessness. And although I wish I had the opportunity to seek his counsel, I’m grateful that his cartoons and his legacy live on.