The Arizona Republic started tracking undocumented immigrant deaths in 2003 using medical examiner, foreign consulate, and law enforcement reports. Susan Carroll wrote the following words to introduce a published list of the 205 bodies or skeletal remains found that year in Arizona.

It is a lonely place to die, out in the soft sandy washes. The desert floor, with its volcanic rock, can reach 160 degrees. Most people go down slowly. Blood starts to seep into the lungs. Exposed skin burns and the sweat glands shut down. Little hemorrhages, tiny leaks, start in the heart. When the body temperature reaches 107, the brain cooks and the delirium starts.

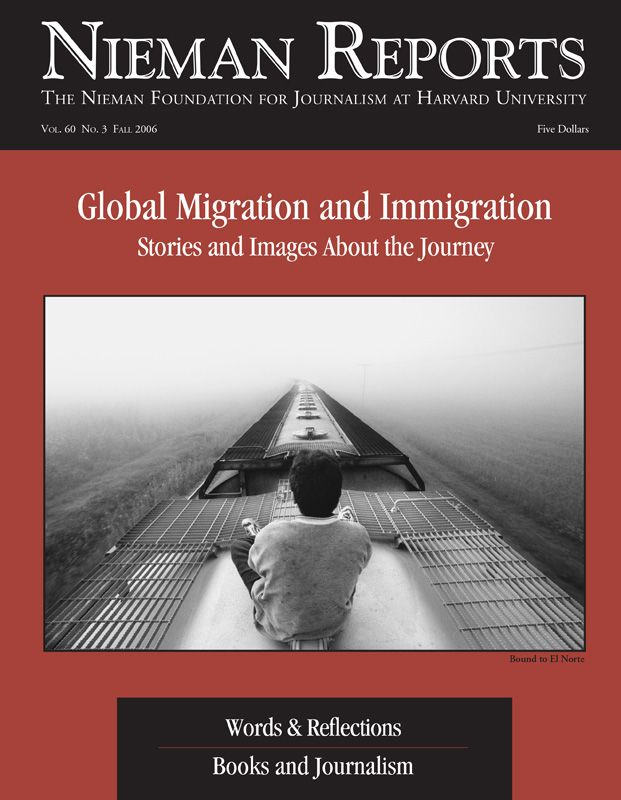

RELATED ARTICLES

"Reporting on the Deaths of Those Who Make the Journey North"

– By Susan Carroll

"Rescue and Death Along the Border"

– Photos by Pat ShannahanSome migrants claw at the ground with their fingernails, trying to hollow out a cooler spot to die. Others pull themselves through the sand on their bellies, like they're swimmers or snakes. The madness sometimes prompts people to slit their own throats or to hang themselves from trees with their belts.

This past year, the bodies of 205 undocumented immigrants were found in Arizona. Official notations of their deaths are sketchy, contained in hundreds of pages of government reports. Beyond the official facts, there are sometimes little details, glimpses, of the people who died. Maria Hernandez Perez was No. 93. She was almost two. She had thick brown hair and eyes the color of chocolate. Kelia Velazquez-Gonzalez, 16, carried a Bible in her backpack. She was No. 109.

In some cases, stories of heroism or loyalty or love survive. Like the Border Patrol agent who performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a dead man, hoping for a miracle. Or the group of migrants who, with law officers and paramedics, helped carry their dead companion out of the desert. Or the husband who sat with his dead wife through the night.

Other stories are almost entirely lost in the desolate stretches that separate the United States and Mexico. Within weeks, the heat makes mummies out of men. Animals carry off their bones and belongings. Many say their last words to an empty sky. John Doe, No. 143, died with a rosary encircling his neck. His eyes were wide open.

It is a lonely place to die, out in the soft sandy washes. The desert floor, with its volcanic rock, can reach 160 degrees. Most people go down slowly. Blood starts to seep into the lungs. Exposed skin burns and the sweat glands shut down. Little hemorrhages, tiny leaks, start in the heart. When the body temperature reaches 107, the brain cooks and the delirium starts.

RELATED ARTICLES

"Reporting on the Deaths of Those Who Make the Journey North"

– By Susan Carroll

"Rescue and Death Along the Border"

– Photos by Pat ShannahanSome migrants claw at the ground with their fingernails, trying to hollow out a cooler spot to die. Others pull themselves through the sand on their bellies, like they're swimmers or snakes. The madness sometimes prompts people to slit their own throats or to hang themselves from trees with their belts.

This past year, the bodies of 205 undocumented immigrants were found in Arizona. Official notations of their deaths are sketchy, contained in hundreds of pages of government reports. Beyond the official facts, there are sometimes little details, glimpses, of the people who died. Maria Hernandez Perez was No. 93. She was almost two. She had thick brown hair and eyes the color of chocolate. Kelia Velazquez-Gonzalez, 16, carried a Bible in her backpack. She was No. 109.

In some cases, stories of heroism or loyalty or love survive. Like the Border Patrol agent who performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a dead man, hoping for a miracle. Or the group of migrants who, with law officers and paramedics, helped carry their dead companion out of the desert. Or the husband who sat with his dead wife through the night.

Other stories are almost entirely lost in the desolate stretches that separate the United States and Mexico. Within weeks, the heat makes mummies out of men. Animals carry off their bones and belongings. Many say their last words to an empty sky. John Doe, No. 143, died with a rosary encircling his neck. His eyes were wide open.