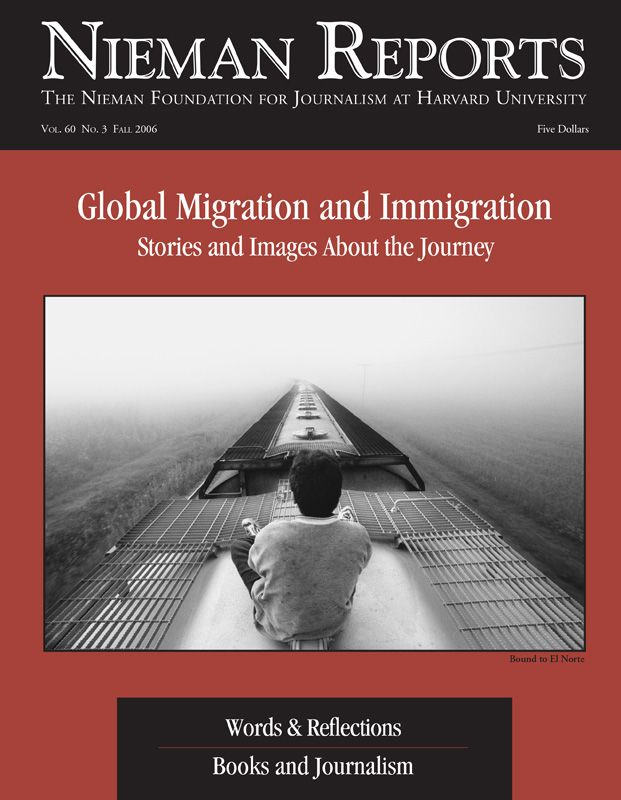

Global Migration and Immigration: Stories and Images About the Journey

When I was a border correspondent, I learned to move between both sides, quickly and frequently, physically and mentally, while striving for balance. I learned to maneuver in gray areas. And I learned there was no substitute for being out in the field, on the street, at the line — talking with migrants and cops and desperados, the gatekeepers of the secret worlds.

I keep the autopsy reports in cardboard filing boxes labeled with "Border Deaths" and the year in which they were found. I have hundreds of reports, each an incomplete story — a baby girl dressed in a green jumper, a 16 year old with a Bible in her backpack, a young man dressed like he was going to school wearing a herringbone sweater. His report is only a few pages. Besides the sweater all that was left of him was bones.

I put these boxes in a closet a few months ago because I got tired of looking at them. Many of these reports remind me of stories I never got around to telling. Others take me back to places I would like to forget in the desert where the smell of the creosote after a monsoon rain mingles with the stench of decomposition.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Death in the Desert"

– By Susan CarrollCovering deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border is challenging but also incredibly rewarding. These stories are often unpopular with readers and difficult to tell because they require strong support from editors. They often necessitate reporting along the border and deep into Mexico to find survivors or family members. Over the years, I've struggled to balance objectivity and compassion as I've stood with my tape recorder rolling as an agent tries to save a dying woman in the remote desert. I've also run into major problems getting an accurate count of border deaths from the U.S. Border Patrol. It's not that officials in Washington, D.C. have the information and are refusing to give it out; they don't track all of the deaths. To arrive at a more accurate count, journalists have to take on an independent watchdog role and pull together the statistics from medical examiners, foreign consulates, and law enforcement along the border.

In The Arizona Republic's newsroom, we've struggled to decide how to cover the rising number of deaths. Do we write brief mentions of each one? Not usually. Sometimes our coverage seems like a sad numbers game. A dozen deaths in a weekend typically warrants an inside story. But day after day, who will read about a body here and a body there? We've tried to avoid writing articles that just recite the number of deaths recorded by the Border Patrol in its fiscal year, declare it to be a new record, and quote a spokesperson. Instead, we focus on telling stories about the people who have died, and then we also investigate more fully the number of deaths recorded as a way of holding the government accountable for its tally.

With the mounting anti-illegal immigration backlash, readers have complained more and more about the stories we do about the deaths. They believe that in doing these stories the newspaper is being sympathetic to people who break the law. As the person at the paper who reports on this topic most often, I am grateful that my editors and those at other newspapers — such as the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post — remain committed to giving reporters the space and time they need to tell these stories.

Tracking the Lives of the Dead

In the five years I've been doing this kind of reporting, I've found that the best way is to start out on the ground with the U.S. Border Patrol's elite search and rescue team that responds to calls for medical help in the desert. I've been on ride-alongs when eight bodies have been found in a single day. And there has been no effort to restrict my access.

For me, the story — and my reporting — often starts with the discovery of the body. If no relatives or friends stayed to search for help, there is often little information, aside from perhaps a Mexican ID card, to trace the trail back to a family member. Foreign consulates are typically very helpful with information on the hometowns of the people who die, but I've run into major logistical problems when I've traveled to towns with no regular bus service to try to visit families that have no telephone. Sometimes, there is no other way to get these stories than to simply go there and take the chance that if you're respectful and speak Spanish, family members and friends of the victim will talk with you.

These stories also reach into immigrant communities in small-town America and our nation's big cities. Many of the undocumented immigrants who die on their journey north are coming here to join relatives already living in the United States. Mexican consulates near the families of the dead typically are notified very quickly and often can be a great resource for these stories for reporters who are not based on the border.

With the issue of border numbers, U.S. newspapers need to closely monitor the way the U.S. Border Patrol tracks deaths. They didn't start keeping records until the 1998-1999 fiscal year and tailored the criteria to be very narrow: The migrant must be in the process of crossing and within a certain distance from the border to be included in their count. Most difficult of all is the requirement that there be some kind of proof that the person who died was undocumented. In some cases, they only count the death if an agent found the body or if it was reported directly to them by another law enforcement agency. At one point, the Tucson sector, the deadliest along the border, quietly changed its counting method without telling journalists; they excluded skeletal remains and smugglers from their count and then claimed that border deaths had decreased.

The Border Patrol in Arizona recently modified counting methods and now works more closely with medical examiners, but I suspect the problem of underreporting deaths spans the entire U.S-Mexico border. I sometimes wonder how many undocumented immigrants were buried in paupers' graves but never were tallied by the Border Patrol because no one is holding the federal government accountable.

I try not to dwell on these deaths, but sometimes I think about the day I saw the woman die out in the desert. The undocumented immigrant who flagged down the Border Patrol stood there with me as her ragged breathing stopped. The words the officer spoke to me at that moment have stayed with me since that day. "At times," he said, "one has regrets." When I wrote the story on the woman's death, the morgue was backed up, and it took weeks to identify her body. So when we went to press, I didn't even know her name yet. It was Raquel Hernandez Cruz. I wish that was in the story.

As immigration has grown into a major, national news story, newspapers from across the country have done excellent work covering border deaths, explaining the economic forces that drive massive immigration and telling the stories of those who died. But I wondered earlier this summer, as I shopped for more boxes for more autopsy reports, if we're really doing enough.

Susan Carroll has covered the U.S.-Mexico border for five years. She is a senior reporter, based in Tucson, for The Arizona Republic. She has twice been named Arizona's Virg Hill Journalist of the Year.

I put these boxes in a closet a few months ago because I got tired of looking at them. Many of these reports remind me of stories I never got around to telling. Others take me back to places I would like to forget in the desert where the smell of the creosote after a monsoon rain mingles with the stench of decomposition.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Death in the Desert"

– By Susan CarrollCovering deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border is challenging but also incredibly rewarding. These stories are often unpopular with readers and difficult to tell because they require strong support from editors. They often necessitate reporting along the border and deep into Mexico to find survivors or family members. Over the years, I've struggled to balance objectivity and compassion as I've stood with my tape recorder rolling as an agent tries to save a dying woman in the remote desert. I've also run into major problems getting an accurate count of border deaths from the U.S. Border Patrol. It's not that officials in Washington, D.C. have the information and are refusing to give it out; they don't track all of the deaths. To arrive at a more accurate count, journalists have to take on an independent watchdog role and pull together the statistics from medical examiners, foreign consulates, and law enforcement along the border.

In The Arizona Republic's newsroom, we've struggled to decide how to cover the rising number of deaths. Do we write brief mentions of each one? Not usually. Sometimes our coverage seems like a sad numbers game. A dozen deaths in a weekend typically warrants an inside story. But day after day, who will read about a body here and a body there? We've tried to avoid writing articles that just recite the number of deaths recorded by the Border Patrol in its fiscal year, declare it to be a new record, and quote a spokesperson. Instead, we focus on telling stories about the people who have died, and then we also investigate more fully the number of deaths recorded as a way of holding the government accountable for its tally.

With the mounting anti-illegal immigration backlash, readers have complained more and more about the stories we do about the deaths. They believe that in doing these stories the newspaper is being sympathetic to people who break the law. As the person at the paper who reports on this topic most often, I am grateful that my editors and those at other newspapers — such as the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post — remain committed to giving reporters the space and time they need to tell these stories.

Tracking the Lives of the Dead

In the five years I've been doing this kind of reporting, I've found that the best way is to start out on the ground with the U.S. Border Patrol's elite search and rescue team that responds to calls for medical help in the desert. I've been on ride-alongs when eight bodies have been found in a single day. And there has been no effort to restrict my access.

For me, the story — and my reporting — often starts with the discovery of the body. If no relatives or friends stayed to search for help, there is often little information, aside from perhaps a Mexican ID card, to trace the trail back to a family member. Foreign consulates are typically very helpful with information on the hometowns of the people who die, but I've run into major logistical problems when I've traveled to towns with no regular bus service to try to visit families that have no telephone. Sometimes, there is no other way to get these stories than to simply go there and take the chance that if you're respectful and speak Spanish, family members and friends of the victim will talk with you.

These stories also reach into immigrant communities in small-town America and our nation's big cities. Many of the undocumented immigrants who die on their journey north are coming here to join relatives already living in the United States. Mexican consulates near the families of the dead typically are notified very quickly and often can be a great resource for these stories for reporters who are not based on the border.

With the issue of border numbers, U.S. newspapers need to closely monitor the way the U.S. Border Patrol tracks deaths. They didn't start keeping records until the 1998-1999 fiscal year and tailored the criteria to be very narrow: The migrant must be in the process of crossing and within a certain distance from the border to be included in their count. Most difficult of all is the requirement that there be some kind of proof that the person who died was undocumented. In some cases, they only count the death if an agent found the body or if it was reported directly to them by another law enforcement agency. At one point, the Tucson sector, the deadliest along the border, quietly changed its counting method without telling journalists; they excluded skeletal remains and smugglers from their count and then claimed that border deaths had decreased.

The Border Patrol in Arizona recently modified counting methods and now works more closely with medical examiners, but I suspect the problem of underreporting deaths spans the entire U.S-Mexico border. I sometimes wonder how many undocumented immigrants were buried in paupers' graves but never were tallied by the Border Patrol because no one is holding the federal government accountable.

I try not to dwell on these deaths, but sometimes I think about the day I saw the woman die out in the desert. The undocumented immigrant who flagged down the Border Patrol stood there with me as her ragged breathing stopped. The words the officer spoke to me at that moment have stayed with me since that day. "At times," he said, "one has regrets." When I wrote the story on the woman's death, the morgue was backed up, and it took weeks to identify her body. So when we went to press, I didn't even know her name yet. It was Raquel Hernandez Cruz. I wish that was in the story.

As immigration has grown into a major, national news story, newspapers from across the country have done excellent work covering border deaths, explaining the economic forces that drive massive immigration and telling the stories of those who died. But I wondered earlier this summer, as I shopped for more boxes for more autopsy reports, if we're really doing enough.

Susan Carroll has covered the U.S.-Mexico border for five years. She is a senior reporter, based in Tucson, for The Arizona Republic. She has twice been named Arizona's Virg Hill Journalist of the Year.