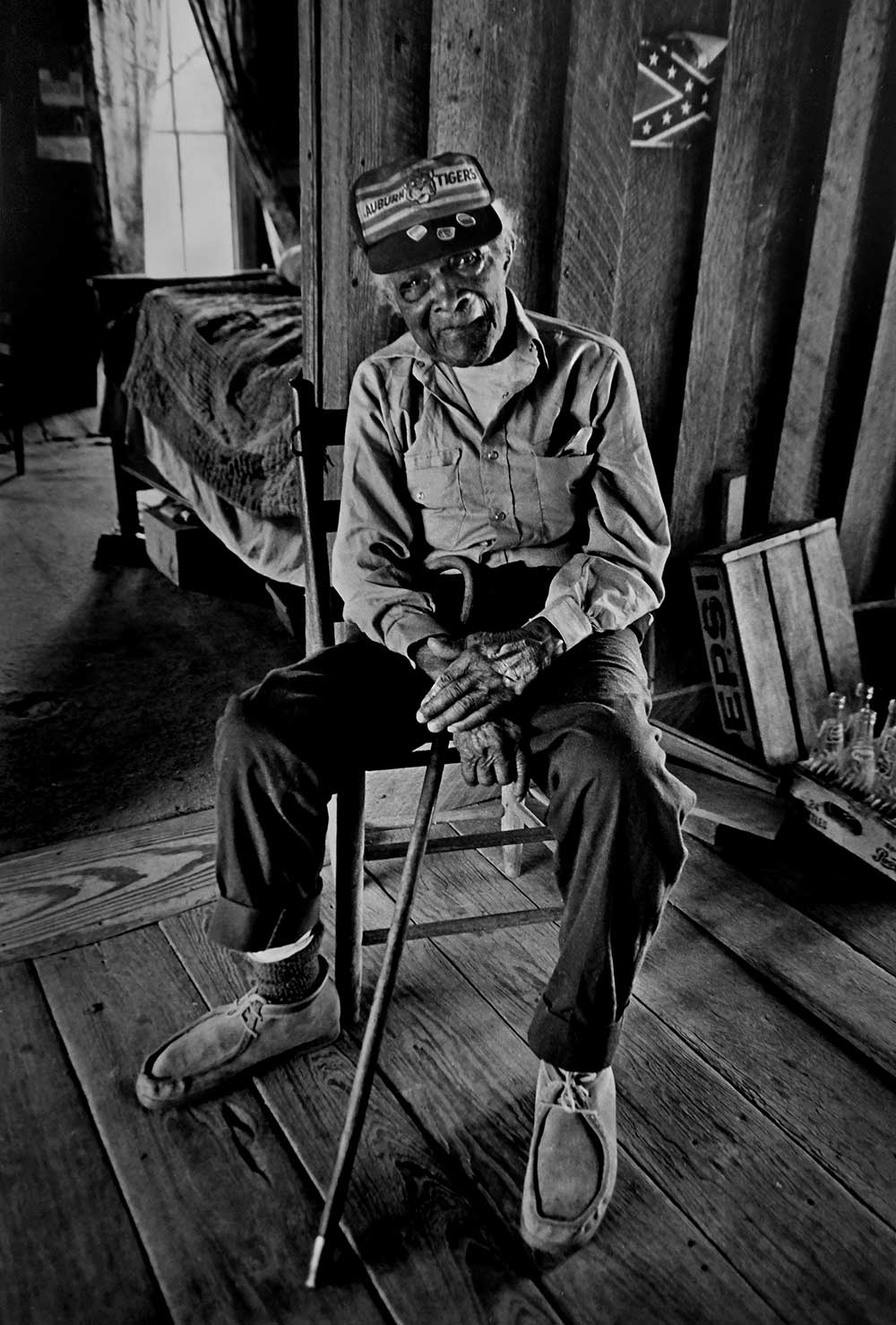

Maharidge and Williamson revisited rural Alabama to find out what happened to the families of the poor sharecroppers chronicled by another writer-photographer pair, James Agee and Walker Evans, in the 1941 book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” In the process, they reported on the collapse of the tenant farming system.

Frank points to twenty acres of tall grass across the road, an overgrown field between the pavement and the distant tree line. By squinting, one can faintly see finger pines poking through the matted blades in the fading light of dusk.

“You see that lan’ over there? I was workin’ it. Now it’s ’n pine. They planted them a few years ago. That white woman won’ sell it. And she won’ rent it. She jus’ planted it ’n pine. It’s like that all roun’ here. Them whites jus’ won’ rent the lan’, let anyone farm.”

They are landlocked by white landowners on all sides. Those landowners control vast holdings, and Gaines views them as their largest difficulty. That twenty-acre section is part of the cotton land he worked for Mr. Gumbay long ago. It is still owned by Mrs. Gumbay. He’d like to plow it again in order to raise food on it to feed his family. If he could plant corn there, he says, they’d be able to survive better. “Me and my fam’ly can do it, but it ain’ ’nough,” says Frank of the farming they used to do to supplement their scant income. Now, in summer, a plane descends and sprays that land with herbicides, to kill the weeds that might compete with the pines.

The Gaineses are trapped in this bend of the river, still affected by a plantation matriarch. In 1986, the cycle of change brought by the collapse of the cotton empire is not complete. Rural blacks like Gaines are still trying to cope. The old ones are stuck here. Many of the young ones can no longer go north for jobs. That escape valve has been closed to them. The land, more and more of it now forested, is off-limits and unavailable as an instrument of support for them. There seems to be no easy solution in sight for people like the Gaineses.

Excerpt from AND THEIR CHILDREN AFTER THEM by Dale Maharidge and Michael Williamson. Originally published by Pantheon, 1989; now published by Seven Stories Press.