During the explosive spread of the SARS virus, in the land of its origin, the media were preoccupied with weighty political stories. Changes in China’s domestic leadership at home, along with the distraction of America’s preemptive war on Iraq, dominated the news, making it easy for a “local” medical story in southern China’s Guangdong region to slip under the radar all but unnoticed, for reasons inadvertent and intentional.

Bookended by the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in November (which was dominated by the change of guard from third to fourth generation of Chinese Communist leadership, a once in a generation event) and twin meetings of the China National People’s Consultative Congress and the National People’s Congress in March, the mystery disease—soon to be known as SARS—spread while attention was focused elsewhere. There wasn’t much space in newspapers or broadcast time available for any story, especially a gloomy one, as the state media kicked into good-news gear to shower people with confidence-building stories and political theater. Even the relatively racy tabloid press, which gave the changing of the guard story short shrift, failed to focus on SARS as exotic military matters in Iraq and North Korea were boosting newsstand sales.

Missing Its Own Story

RELATED ARTICLE

"War Coverage in the Chinese Media"

- Yuan FengDuring the walk-up to the Iraq war and while it was being waged, CCTV (China’s state-run television station), in particular, benefited from the nation’s relatively neutral stance to provide balanced, factual reporting on military and diplomatic developments in a way that seemed to herald the arrival of serious TV journalism in China. The tragedy, however, is that while CCTV’s coverage rose to that occasion to present news that was in some respects equal to or even superior to the patriotic pabulum being broadcast by U.S. stations, a huge story was brewing in CCTV’s backyard, and it went almost entirely unreported.

The chronic emergence of influenza strains during the cold season made it possible for the SARS outbreak to be cast as just another seasonal flu story, putting it on the back burner until it exploded and couldn’t be ignored any longer. CCTV (and other local news organizations) offered only infrequent, vague accounts of the bad flu that hit Guangdong, giving the impression it was a regional sickness that wreaked havoc and disappeared. For a while, it did disappear, at least from news reports. Then SAR (Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong) got hit by something that was, ironically, named SARS. This served to strengthen the impression that this was a problem centered on Hong Kong and unrelated to China.

To the world, this illness was an Asian thing; in Asia, a Chinese thing; in China, a Hong Kong thing; in Hong Kong, a Kowloon thing; in Kowloon, a Metropole Hotel thing; in The Metropole Hotel, a ninth-floor thing, and on the ninth floor, it was a sneeze from a doctor who picked it up in Guangdong. In Guangdong, it was a Foshan thing; in Foshan it was blamed on a chef, and so on. While the exact ground zero of SARS is unknown, the blame game was being practiced at every level.

The Chinese Government’s Role

While the weight of scientific opinion pointed heavily to Guangdong as the origin of this mysterious “Chinese fever,” face-conscious Chinese officials claimed that Hong Kong’s SARS was an unrelated disease, and they subsequently made feverish attempts to downplay scientific evidence and give rise to rumors suggesting SARS was from somewhere else. (It is certainly possible some Chinese health experts believed the flu in Guangdong to be unrelated to the SARS in Hong Kong because so much was unknown about the disease, with its shifting patterns of infection and uncertainty about its infectious agent.) There was media speculation suggesting the cause might be bioterrorism and somehow linked to the war.

Some health officials even slyly started suggesting SARS was an import, even a “foreign thing,” and a malicious disinformation program went into full swing. The Chinese Ministry of Health and its media minions exploited the fact that several publicly scrutinized SARS deaths involved Europeans—Italian doctor Carlos Urbani and Finnish International Labor Organization official Pekka Aro—not so subtly portraying the disease as a foreign import. It was a case of using the facts to confuse instead of elucidate. (Urbani got ill caring for SARS patients in Hanoi and died in Bangkok, but the outbreak in Hanoi is traceable to Guangdong. Aro was said to have picked up the bug on a Thai Airways International plane from Bangkok, but experts can trace the airplane-borne infections to China as well.) In both of these high-profile cases, by telling only half the story the media made it seem that China was uninvolved and exonerated.

From the outset, politics, psychology and science played roles in how China’s government—and the media in China—handled this health crisis. To the extent that SARS was deliberately unreported it is a miscarriage of journalism and health administration. But even those guilty of suppressing news and statistics in the beginning could hardly have known how badly the gamble to downplay would turn out in the end. Even in a free society like Hong Kong, the SARS story was full of twists and turns, false alarms, and false hopes that it was over. That the disease would turn out to involve a ferocious species-jumping virus that in some people was resistant to top-notch medical care was hard to know at the outset. Who could have predicted the course it would take and how it would frighten people throughout the world due to its mysterious mechanisms of infection?

Even as the disease ripped through Guangdong, causing a run on goods and panic, the story that made it to Beijing readers and viewers was largely a human interest one. Isn’t it curious how southerners panic and resort to home remedies when a bad flu goes around? It wasn’t until the Iraq war was nearly over that SARS hit the radar of public consciousness in Beijing in any substantial way. By then, the disease was so devastating to Hong Kong that news of it started to compete with war stories.

CCTV’s early SARS stories mostly involved trotting responsible officials before the camera to reassure the public that everything was under control and life could go on as normal. But nagging questions remained. Was SARS related to the flu that had hit Guangdong just before Chinese New Year when interprovince travel was at its peak? If so, why wasn’t there any evidence of sickness in Beijing and other cities? Why was the first outbreak in Guangdong not covered in the press? Instead, news of it traveled largely on telephone text messaging to reach people in and out of China. Had the people of Guangdong made a big fuss about nothing or had they faced the same viral terror as the people in Hong Kong?

Enterprising local journalists tried to answer some of these questions and hit a wall, revealing later that there had been a memo ordering them off the story. Similarly, foreign reporters interested in the SARS story complained about lack of cooperation on the Chinese side. Even when the Health Ministry started to offer briefings, members of the Beijing press corps were frustrated by unresolved contradictions—sometimes the toll was said to include military hospitals, other times it was said it didn’t—and inaccurate statistics.

By late March, the Health Ministry had a choice—to admit it was lying or go on lying and compound the problem. It chose to go on lying and stonewalling. Officials from the World Health Organization (WHO) were given a cold reception in Beijing, and requests to visit Guangdong were put in abeyance. On March 25th, the Health Ministry announced, “We have not found a single case of atypical pneumonia in Beijing or any other place in China recently.” The clay feet of China’s Health Ministry were exposed when it turned out that Beijing was badly infected with SARS.

Rather than immediate and complete transparency to save lives and advance science, the public was kept in the dark by nervous officials hoping SARS would go away or at least go by unnoticed. The body of an American teacher who was dying of SARS in Shenzhen was whisked across the border to Hong Kong. This story gave rise to the impression that a foreigner with SARS was an unwanted hot potato and could expect little compassion from worried authorities. In fact, this teacher was being sent there belatedly and at his family’s request. But the Orwellian overtones of a story, in which neither side of the boundary wanted the statistical burden of SARS death, had been established.

That the first few foreigners to succumb to SARS received considerable media attention in China, while the more numerous Chinese victims died unrecognized and unknown, served to propagate the official line that “there is no proof this disease is from China.” Like China’s clumsy handling of AIDS, it looked for a while like this one, too, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, would be blamed on foreigners.

By the end of March, China’s media were giving mixed signals, a clear indication that the SARS crisis was provoking a political power struggle. President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao, and Wu Yi (known as the “Iron Lady,” one of the few women in top leadership who would, in time, replace the health minister) were the first to speak out. Former President Jiang Zemin and his politburo proxies such as Zeng Qinghong and Jia Qingling were strangely silent. SARS seemed to sneak up and take these top government officials by surprise. Those responsible for the cover-up such as Health Minister Zhang Wenkang, Beijing Mayor Meng Xuenong, and other Jiang protégés were subsequently fired, suggesting Hu and Wen—when they decided to act—risked their political careers to get rid of deadwood and tackle the SARS problem head on.

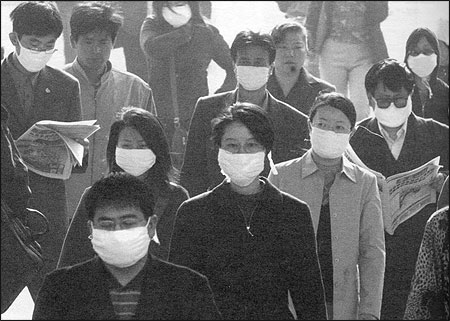

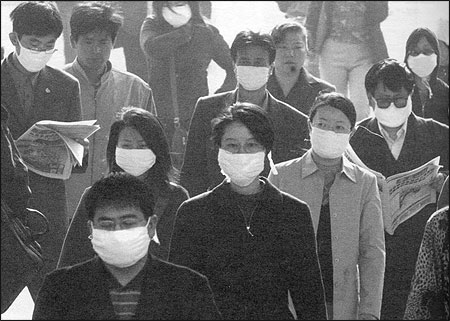

Chinese people go to work with masks in Beijing, China. Public alarm about the SARS virus soared as reports surfaced of a much higher SARS figure and authorities cranked up an anti-SARS propaganda drive--one of China’s most aggressive and sweeping campaigns in years. Photo by Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press.

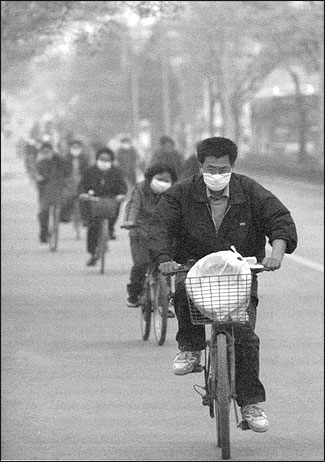

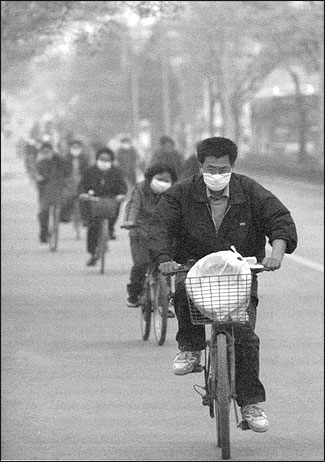

Cyclists wear masks to protect themselves from SARS in Beijing. Photo by Kyodo News/The Associated Press.

Cultural Influences on Media

What is impossible to know—because press coverage of such things is not allowed—is whether Jiang, who was leaving as president, wanted nothing to mar his political swan song and thus SARS was covered up maliciously. But what we do know is that just as streets were swept clean, houses of ill-repute temporarily padlocked, grass painted green and petty criminals rounded up, so, too, newspapers and airwaves got a superficial clean-up in November to celebrate the “success” of the scripted 16th Party Congress as it celebrated the Jiang era. It is also true that one of the many jobs of China’s self-appointed guardians is to reassure and calm people, since the Chinese have a history of hysterical overreaction to perceived threats. Likewise, there is the customary whitewash, employed on ritual occasions, to block inauspicious things from view in order to present China in the best possible light.

So it might have been by coincidence rather than design that the curtain of silence came down on the press just as the virus was beginning to spread. But once damage mounted, news reports of death and plague would surely have detracted from Jiang’s farewell party and this celebration of his days in power. During these early stages, the government and media whitewash was not nearly as criminal in intent as the deliberate stonewalling, statistical understatement, and outright lying that happened later.

After the 16th Party Congress ended, restraints on behavior, including those put on journalists, loosened. Illegal CD’s were back on the market. Street vendors camped on bridges and street corners and red lights glowed once again. And reporters, within reason, could begin to dig for stories. Soon stories from foreign media were being picked up and translated. Among them were reports about the mystery flu in southern China, and these stories—reported by independent press in Hong Kong and foreign news agencies—carried with them increased credibility.

Still, in China, the disease was swept under the rug until reports about SARS from Hong Kong, Vietnam, Taiwan and other secondary locations bounced back into China via the Internet, Phoenix satellite TV news, and word of mouth. Complacency was still being peddled by the spinmasters of China’s state-controlled press. Several Chinese reporters complained they were warned off the SARS story. There was also the unexplained closing of several Guangzhou-based publications, which some thought might have been related to this issue. Informed speculation about the closing of the 21st Century Herald hints at central government displeasure at a critique of lagging political reform, effectively silencing one of the most outspoken media outlets in Guangzhou, the first city hit by SARS. The author of an Internet communication claiming government statistics were lies got in trouble, and two Xinhua editors were reported to be sacked for publicizing a classified document on SARS, though they were reassigned jobs elsewhere in the news agency.

There was an additional cultural factor that delayed dissemination of bad news. In the middle of flu season, the Year of the Sheep was to be welcomed. Chinese New Year is the country’s most important holiday and individuals, much like the government, believe that inauspicious topics should be avoided in favor of merriment. Family reunions are essential, and the seasonal movement involves mind-boggling numbers of people: Some 100 million migrant laborers travel by bus and train to homes in the countryside of China. This year’s holiday, arriving on the heels of years of economic growth, political stability and visible prosperity, involved perhaps the largest movement of human beings in the history of the world as a nation of a billion people raced home. This presented the understandable, if risky, desire not to ruin the holiday by announcing the danger of disease and urging people not to travel or, perhaps, even canceling the holiday.

The Role the Internet Played

Hong Kong took the heat of being the epicenter of SARS not because it started there but because it was the disease’s first outbreak in a place with a free press. The death toll and infection rate in Guangdong was not comprehensively reported, nor was the slightest indication given that a “regional” disease could have any impact on Beijing or the rest of China. When doctors in Hong Kong and China were initially quoted in press accounts, their pessimistic comments and dark scenarios were much out of tune with the public mood. The South China Morning Post in Hong Kong played a key role in the dissemination of information about SARS during this stage, since SARS was seen by the media and in medical terms as a “Hong Kong” story. Whatever happened in Guangdong was, for the time being, difficult to report and nearly impossible to research.

The Ministry of Health wasted hours of primetime television that was made available to tell their side of the story by making light of the whole matter. Deputy Minister Ma took a light-hearted, affable approach, saying facemasks were unnecessary and it was much ado about nothing. It’s as simple as “one, two, three, four, five, see, nothing to be afraid of,” he said, as he tried to talk away fears by using party-line charm. His boss, Zhang Wenkang, went on record defying the facts.

Contributing to the dearth of reliable information about SARS was the weakened state of the Internet in China during the winter of 2003. Censorship of foreign news stories was quite heavy and Internet access limited. While the SARS virus was starting to spread, Internet cafés, tightly regulated and under observation, were just starting to be reopened after lengthy nationwide closures in the name of unregulated business and fire hazards. China boasts millions of Web surfers, but relatively few computer owners; public access computers in campus libraries and Internet cafés are essential to the Web having a vibrant role in information flow.

Many Web sites—including The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Daily Telegraph, ABC News, and CNN—were banned. But by using proxies and reading wire service accounts it was possible to get a pretty good idea about what the outside world was saying about China. But access was spotty and inconvenient. I wrote about this situation for the South China Morning Post in February, arguing that China had more to lose than gain by blocking credible news sites.

The ban on these sites and others was lifted a few weeks later, just as the season of Party Congresses was coming to a climax. Some have speculated on the timing, suggesting this gesture towards transparency marked the transition in generational leadership. If this is so, then perhaps transparency and increased media freedom can be expected to be part of the new administration’s policy under the leadership of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao.

Courageous Voices Break the Story

In early April, several courageous Chinese individuals came forward to say that their government was lying. At this time, the official line admitted to only a handful of “imported” cases. One doctor was reportedly fired for telling a wire service reporter about confirmed SARS cases in the capital. But the big breakthrough happened when a respected military doctor named Jiang Yanyong told foreign reporters on the record that he knew of more than 100 cases and seven deaths in Beijing, none of which had been reported by state officials or media outlets. (Chinese reporters would have had a hard time publishing this information.)

This was the turning point. If the government refused to admit it was wrong, there were fears that this courageous doctor would be punished, possibly imprisoned, and then other doctors would be afraid to speak out. Government bureaucrats, intent on protecting their turf and image, started to crank out propaganda, but it was strange and unconvincing. But at the top level of government, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao went into full gear. They fired recalcitrant officials and admitted, with considerably humility, the failure to grapple with the problem earlier. Strong measures were then put in place to stop the spread of SARS.

By late April, Beijing had become the epicenter of the SARS outbreak. The government has canceled holidays, banned student travel, closed cinemas and karaoke halls, and built emergency medical facilities to accommodate thousands of very sick people.

There’s a Chinese expression about fixing the pen only after sheep escape, but there is also a saying that fixing it late is better than not fixing it at all. In its handling of SARS, China moved from dysfunctional underreaction to dynamic overreaction. And, along the way, the media in that country found themselves unable to inform the people about circumstances that could affect their lives.

Philip J. Cunningham, a 1998 Nieman Fellow, writes for the South China Morning Post and other publications with a focus on politics and culture in Asia.

Bookended by the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in November (which was dominated by the change of guard from third to fourth generation of Chinese Communist leadership, a once in a generation event) and twin meetings of the China National People’s Consultative Congress and the National People’s Congress in March, the mystery disease—soon to be known as SARS—spread while attention was focused elsewhere. There wasn’t much space in newspapers or broadcast time available for any story, especially a gloomy one, as the state media kicked into good-news gear to shower people with confidence-building stories and political theater. Even the relatively racy tabloid press, which gave the changing of the guard story short shrift, failed to focus on SARS as exotic military matters in Iraq and North Korea were boosting newsstand sales.

Missing Its Own Story

RELATED ARTICLE

"War Coverage in the Chinese Media"

- Yuan FengDuring the walk-up to the Iraq war and while it was being waged, CCTV (China’s state-run television station), in particular, benefited from the nation’s relatively neutral stance to provide balanced, factual reporting on military and diplomatic developments in a way that seemed to herald the arrival of serious TV journalism in China. The tragedy, however, is that while CCTV’s coverage rose to that occasion to present news that was in some respects equal to or even superior to the patriotic pabulum being broadcast by U.S. stations, a huge story was brewing in CCTV’s backyard, and it went almost entirely unreported.

The chronic emergence of influenza strains during the cold season made it possible for the SARS outbreak to be cast as just another seasonal flu story, putting it on the back burner until it exploded and couldn’t be ignored any longer. CCTV (and other local news organizations) offered only infrequent, vague accounts of the bad flu that hit Guangdong, giving the impression it was a regional sickness that wreaked havoc and disappeared. For a while, it did disappear, at least from news reports. Then SAR (Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong) got hit by something that was, ironically, named SARS. This served to strengthen the impression that this was a problem centered on Hong Kong and unrelated to China.

To the world, this illness was an Asian thing; in Asia, a Chinese thing; in China, a Hong Kong thing; in Hong Kong, a Kowloon thing; in Kowloon, a Metropole Hotel thing; in The Metropole Hotel, a ninth-floor thing, and on the ninth floor, it was a sneeze from a doctor who picked it up in Guangdong. In Guangdong, it was a Foshan thing; in Foshan it was blamed on a chef, and so on. While the exact ground zero of SARS is unknown, the blame game was being practiced at every level.

The Chinese Government’s Role

While the weight of scientific opinion pointed heavily to Guangdong as the origin of this mysterious “Chinese fever,” face-conscious Chinese officials claimed that Hong Kong’s SARS was an unrelated disease, and they subsequently made feverish attempts to downplay scientific evidence and give rise to rumors suggesting SARS was from somewhere else. (It is certainly possible some Chinese health experts believed the flu in Guangdong to be unrelated to the SARS in Hong Kong because so much was unknown about the disease, with its shifting patterns of infection and uncertainty about its infectious agent.) There was media speculation suggesting the cause might be bioterrorism and somehow linked to the war.

Some health officials even slyly started suggesting SARS was an import, even a “foreign thing,” and a malicious disinformation program went into full swing. The Chinese Ministry of Health and its media minions exploited the fact that several publicly scrutinized SARS deaths involved Europeans—Italian doctor Carlos Urbani and Finnish International Labor Organization official Pekka Aro—not so subtly portraying the disease as a foreign import. It was a case of using the facts to confuse instead of elucidate. (Urbani got ill caring for SARS patients in Hanoi and died in Bangkok, but the outbreak in Hanoi is traceable to Guangdong. Aro was said to have picked up the bug on a Thai Airways International plane from Bangkok, but experts can trace the airplane-borne infections to China as well.) In both of these high-profile cases, by telling only half the story the media made it seem that China was uninvolved and exonerated.

From the outset, politics, psychology and science played roles in how China’s government—and the media in China—handled this health crisis. To the extent that SARS was deliberately unreported it is a miscarriage of journalism and health administration. But even those guilty of suppressing news and statistics in the beginning could hardly have known how badly the gamble to downplay would turn out in the end. Even in a free society like Hong Kong, the SARS story was full of twists and turns, false alarms, and false hopes that it was over. That the disease would turn out to involve a ferocious species-jumping virus that in some people was resistant to top-notch medical care was hard to know at the outset. Who could have predicted the course it would take and how it would frighten people throughout the world due to its mysterious mechanisms of infection?

Even as the disease ripped through Guangdong, causing a run on goods and panic, the story that made it to Beijing readers and viewers was largely a human interest one. Isn’t it curious how southerners panic and resort to home remedies when a bad flu goes around? It wasn’t until the Iraq war was nearly over that SARS hit the radar of public consciousness in Beijing in any substantial way. By then, the disease was so devastating to Hong Kong that news of it started to compete with war stories.

CCTV’s early SARS stories mostly involved trotting responsible officials before the camera to reassure the public that everything was under control and life could go on as normal. But nagging questions remained. Was SARS related to the flu that had hit Guangdong just before Chinese New Year when interprovince travel was at its peak? If so, why wasn’t there any evidence of sickness in Beijing and other cities? Why was the first outbreak in Guangdong not covered in the press? Instead, news of it traveled largely on telephone text messaging to reach people in and out of China. Had the people of Guangdong made a big fuss about nothing or had they faced the same viral terror as the people in Hong Kong?

Enterprising local journalists tried to answer some of these questions and hit a wall, revealing later that there had been a memo ordering them off the story. Similarly, foreign reporters interested in the SARS story complained about lack of cooperation on the Chinese side. Even when the Health Ministry started to offer briefings, members of the Beijing press corps were frustrated by unresolved contradictions—sometimes the toll was said to include military hospitals, other times it was said it didn’t—and inaccurate statistics.

By late March, the Health Ministry had a choice—to admit it was lying or go on lying and compound the problem. It chose to go on lying and stonewalling. Officials from the World Health Organization (WHO) were given a cold reception in Beijing, and requests to visit Guangdong were put in abeyance. On March 25th, the Health Ministry announced, “We have not found a single case of atypical pneumonia in Beijing or any other place in China recently.” The clay feet of China’s Health Ministry were exposed when it turned out that Beijing was badly infected with SARS.

Rather than immediate and complete transparency to save lives and advance science, the public was kept in the dark by nervous officials hoping SARS would go away or at least go by unnoticed. The body of an American teacher who was dying of SARS in Shenzhen was whisked across the border to Hong Kong. This story gave rise to the impression that a foreigner with SARS was an unwanted hot potato and could expect little compassion from worried authorities. In fact, this teacher was being sent there belatedly and at his family’s request. But the Orwellian overtones of a story, in which neither side of the boundary wanted the statistical burden of SARS death, had been established.

That the first few foreigners to succumb to SARS received considerable media attention in China, while the more numerous Chinese victims died unrecognized and unknown, served to propagate the official line that “there is no proof this disease is from China.” Like China’s clumsy handling of AIDS, it looked for a while like this one, too, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, would be blamed on foreigners.

By the end of March, China’s media were giving mixed signals, a clear indication that the SARS crisis was provoking a political power struggle. President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao, and Wu Yi (known as the “Iron Lady,” one of the few women in top leadership who would, in time, replace the health minister) were the first to speak out. Former President Jiang Zemin and his politburo proxies such as Zeng Qinghong and Jia Qingling were strangely silent. SARS seemed to sneak up and take these top government officials by surprise. Those responsible for the cover-up such as Health Minister Zhang Wenkang, Beijing Mayor Meng Xuenong, and other Jiang protégés were subsequently fired, suggesting Hu and Wen—when they decided to act—risked their political careers to get rid of deadwood and tackle the SARS problem head on.

Chinese people go to work with masks in Beijing, China. Public alarm about the SARS virus soared as reports surfaced of a much higher SARS figure and authorities cranked up an anti-SARS propaganda drive--one of China’s most aggressive and sweeping campaigns in years. Photo by Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press.

Cyclists wear masks to protect themselves from SARS in Beijing. Photo by Kyodo News/The Associated Press.

Cultural Influences on Media

What is impossible to know—because press coverage of such things is not allowed—is whether Jiang, who was leaving as president, wanted nothing to mar his political swan song and thus SARS was covered up maliciously. But what we do know is that just as streets were swept clean, houses of ill-repute temporarily padlocked, grass painted green and petty criminals rounded up, so, too, newspapers and airwaves got a superficial clean-up in November to celebrate the “success” of the scripted 16th Party Congress as it celebrated the Jiang era. It is also true that one of the many jobs of China’s self-appointed guardians is to reassure and calm people, since the Chinese have a history of hysterical overreaction to perceived threats. Likewise, there is the customary whitewash, employed on ritual occasions, to block inauspicious things from view in order to present China in the best possible light.

So it might have been by coincidence rather than design that the curtain of silence came down on the press just as the virus was beginning to spread. But once damage mounted, news reports of death and plague would surely have detracted from Jiang’s farewell party and this celebration of his days in power. During these early stages, the government and media whitewash was not nearly as criminal in intent as the deliberate stonewalling, statistical understatement, and outright lying that happened later.

After the 16th Party Congress ended, restraints on behavior, including those put on journalists, loosened. Illegal CD’s were back on the market. Street vendors camped on bridges and street corners and red lights glowed once again. And reporters, within reason, could begin to dig for stories. Soon stories from foreign media were being picked up and translated. Among them were reports about the mystery flu in southern China, and these stories—reported by independent press in Hong Kong and foreign news agencies—carried with them increased credibility.

Still, in China, the disease was swept under the rug until reports about SARS from Hong Kong, Vietnam, Taiwan and other secondary locations bounced back into China via the Internet, Phoenix satellite TV news, and word of mouth. Complacency was still being peddled by the spinmasters of China’s state-controlled press. Several Chinese reporters complained they were warned off the SARS story. There was also the unexplained closing of several Guangzhou-based publications, which some thought might have been related to this issue. Informed speculation about the closing of the 21st Century Herald hints at central government displeasure at a critique of lagging political reform, effectively silencing one of the most outspoken media outlets in Guangzhou, the first city hit by SARS. The author of an Internet communication claiming government statistics were lies got in trouble, and two Xinhua editors were reported to be sacked for publicizing a classified document on SARS, though they were reassigned jobs elsewhere in the news agency.

There was an additional cultural factor that delayed dissemination of bad news. In the middle of flu season, the Year of the Sheep was to be welcomed. Chinese New Year is the country’s most important holiday and individuals, much like the government, believe that inauspicious topics should be avoided in favor of merriment. Family reunions are essential, and the seasonal movement involves mind-boggling numbers of people: Some 100 million migrant laborers travel by bus and train to homes in the countryside of China. This year’s holiday, arriving on the heels of years of economic growth, political stability and visible prosperity, involved perhaps the largest movement of human beings in the history of the world as a nation of a billion people raced home. This presented the understandable, if risky, desire not to ruin the holiday by announcing the danger of disease and urging people not to travel or, perhaps, even canceling the holiday.

The Role the Internet Played

Hong Kong took the heat of being the epicenter of SARS not because it started there but because it was the disease’s first outbreak in a place with a free press. The death toll and infection rate in Guangdong was not comprehensively reported, nor was the slightest indication given that a “regional” disease could have any impact on Beijing or the rest of China. When doctors in Hong Kong and China were initially quoted in press accounts, their pessimistic comments and dark scenarios were much out of tune with the public mood. The South China Morning Post in Hong Kong played a key role in the dissemination of information about SARS during this stage, since SARS was seen by the media and in medical terms as a “Hong Kong” story. Whatever happened in Guangdong was, for the time being, difficult to report and nearly impossible to research.

The Ministry of Health wasted hours of primetime television that was made available to tell their side of the story by making light of the whole matter. Deputy Minister Ma took a light-hearted, affable approach, saying facemasks were unnecessary and it was much ado about nothing. It’s as simple as “one, two, three, four, five, see, nothing to be afraid of,” he said, as he tried to talk away fears by using party-line charm. His boss, Zhang Wenkang, went on record defying the facts.

Contributing to the dearth of reliable information about SARS was the weakened state of the Internet in China during the winter of 2003. Censorship of foreign news stories was quite heavy and Internet access limited. While the SARS virus was starting to spread, Internet cafés, tightly regulated and under observation, were just starting to be reopened after lengthy nationwide closures in the name of unregulated business and fire hazards. China boasts millions of Web surfers, but relatively few computer owners; public access computers in campus libraries and Internet cafés are essential to the Web having a vibrant role in information flow.

Many Web sites—including The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Daily Telegraph, ABC News, and CNN—were banned. But by using proxies and reading wire service accounts it was possible to get a pretty good idea about what the outside world was saying about China. But access was spotty and inconvenient. I wrote about this situation for the South China Morning Post in February, arguing that China had more to lose than gain by blocking credible news sites.

The ban on these sites and others was lifted a few weeks later, just as the season of Party Congresses was coming to a climax. Some have speculated on the timing, suggesting this gesture towards transparency marked the transition in generational leadership. If this is so, then perhaps transparency and increased media freedom can be expected to be part of the new administration’s policy under the leadership of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao.

Courageous Voices Break the Story

In early April, several courageous Chinese individuals came forward to say that their government was lying. At this time, the official line admitted to only a handful of “imported” cases. One doctor was reportedly fired for telling a wire service reporter about confirmed SARS cases in the capital. But the big breakthrough happened when a respected military doctor named Jiang Yanyong told foreign reporters on the record that he knew of more than 100 cases and seven deaths in Beijing, none of which had been reported by state officials or media outlets. (Chinese reporters would have had a hard time publishing this information.)

This was the turning point. If the government refused to admit it was wrong, there were fears that this courageous doctor would be punished, possibly imprisoned, and then other doctors would be afraid to speak out. Government bureaucrats, intent on protecting their turf and image, started to crank out propaganda, but it was strange and unconvincing. But at the top level of government, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao went into full gear. They fired recalcitrant officials and admitted, with considerably humility, the failure to grapple with the problem earlier. Strong measures were then put in place to stop the spread of SARS.

By late April, Beijing had become the epicenter of the SARS outbreak. The government has canceled holidays, banned student travel, closed cinemas and karaoke halls, and built emergency medical facilities to accommodate thousands of very sick people.

There’s a Chinese expression about fixing the pen only after sheep escape, but there is also a saying that fixing it late is better than not fixing it at all. In its handling of SARS, China moved from dysfunctional underreaction to dynamic overreaction. And, along the way, the media in that country found themselves unable to inform the people about circumstances that could affect their lives.

Philip J. Cunningham, a 1998 Nieman Fellow, writes for the South China Morning Post and other publications with a focus on politics and culture in Asia.