Jack Saul, a public health psychologist who works in New York City with survivors of political violence and torture refugees, introduced the panel “Speaking Horror: Truth, Accountability and Reconciliation,” which explored telling the stories of trauma through public and private testimony in truth and reconciliation commissions and other forums. Saul’s remarks and those of the three speakers addressing sociopolitical challenges in Northern Ireland, Chile and Kosovo appear as edited excerpts.

It’s been researched that many trauma symptoms subside after going through the testimonial process. We also see that giving testimony in different kinds of contexts, whether legal, artistic or as an oral history, provides a reason for survivors to tell their story that they may not find so quickly in the therapeutic sessions. In fact, many of the survivors I’ve worked with want and seek this kind of public forum for the recognition and as a form of redress. We see now many situations such as truth and reconciliation commissions, testimonies, archives, different contexts in which people are telling their stories. It is not just individual narration that is being developed, but it is collective narration.

Seamus Kelters is assistant news editor with the BBC Northern Ireland. He covered Belfast for 20 years, 16 of them with the BBC. He co-authored “Lost Lives,” chronicling the stories of men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles.

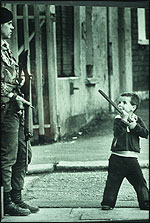

I and a lot of others grew up with a 40-year conflict with 3,700 people dead, 50,000 wounded, and at least 9,000 jailed. If that seems small-scale, it was. We received undue focus because we were white and spoke English. Conveniently on our doorsteps were television, print and radio newsrooms full of young journalists eager to cut their reporting teeth. Our Troubles, and that is what we called our conflict, received coverage, too.

People segregated for 400 years live at opposite ends of the same street. Along those fault lines of sectarian divide was always the angry noise of violence. When it spewed onto the streets again 40 years ago in August 1969, it was familiar to older people. We’d had our troubles before. Police shot my grandfather when he was 17 years old, and he was badly wounded. Another relative of mine was killed in Belfast in 1921 as he walked toward my grandmother; a sniper shot him in the head. I grew up with these stories.

The book, “Lost Lives,” grew out of that family memory. The details of the shooting recorded in the only book on the subject were wrong. Working as a print journalist, and with official and unofficial records and communal knowledge weathering, I realized that no matter how many funerals and bodies we covered, the most recent troubles would not be adequately recorded.

“Lost Lives” was squarely a work of journalism. In close to a million words, we attempted to record not just the names, but the detail of each person’s life and death to the fullest extent possible. Working chronologically, we recorded every fact we could test. We knew the work would cause pain. Although some credited “Lost Lives” with having contributed to the peace process, we never saw it as our job to make things better.

We cannot necessarily do justice to the dead. Ink isn’t blood, but as journalists our first duty was to the record. We became almost obsessed with facts, reality and truth as far as we could find it. As important as what we said was the way we said it. David McKittrick, one of my coauthors, was born in the Loyalist Shankill Road heartland. I came from the fiercely Republican Falls Road and we did most of the writing between us. Five of us though were working across the material and we needed a style guide. So each entry starts with three introductory lines; in those three lines we list the age, the victim’s name, date of death, marital status, number of children they had, religion and occupation.

We estimate there are 22,000 pieces of information in those first three lines alone before we get anywhere near the text where we wanted to write at length about each life and each death. What started as a simple advisory note mushroomed into a style guide which in itself was 50,000 words. Working and living in a divided society, to record that conflict we’d have to be respectful to the other side with our language and be aware of the sensitivities of victims’ relatives. Also, we had to be aware of the truth. In our book, which is close to a million words, unless it is within quotation marks, we don’t use the term “terrorist.” We don’t use the words “freedom fighter.”

Most controversial were the times when we were writing and we were inclusive. So the perpetrators can be found in the pages alongside the victims. We made no judgments of right or wrong. To some extent that was unnecessary in a place where so many of those are confirmed in the cradle. We didn’t spare facts, but we took other cares in our language. We had access to some coroners’ files, but we didn’t feel it appropriate to introduce pathological descriptions. The families of the dead, we felt, knew that all too graphically already and we did not need to pander to any voyeuristic darkness.

Most of our material came from newspaper combings. Some of it also originated with our own journalistic trusted sources and a few came from personal experience. I saw my first person shot dead when I was nine years old. Two years later, I helped to hold someone together after he’d been shot. Many of my primary school class joined the IRA. At least one was shot, several were killed, and I don’t know how many were jailed.

In the first edition of “Lost Lives,” we dedicated it to children that they might learn the lessons. Of all the journalists I know who have covered those troubles not one of them tells the stories to our children. So one of the things that I always take away from events like this and one of the points that I always make at home is how much better a journalist I would have been if I would have had this vocabulary 20 years or more ago when I was just starting. It is something that I think all of us can help young journalists with.

At the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication, Marc Cooper is a journalism professor, director of Annenberg Digital News, and associate director of the Institute for Justice and Journalism. His memoir of Chile, “Pinochet and Me,” describes his experiences as a translator for Chilean President Salvador Allende and his escape from Chile after the 1973 military coup.

Being in Chile during those 17 years of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship was a surreal experience. Everybody who wanted to know knew that people were being tortured and that they were being disappeared. There was no rule of law, only complete and arbitrary and unaccountable use of terror, but you could speak about it only under penalty of death, literally.

There was a truth commission in Chile that was established right at the time of Pinochet’s having lost his own plebiscite that he couldn’t rig properly. What was very upsetting about that was an amnesty law that he’d put into effect made it impossible to prosecute anybody who was found to have committed any of these crimes. We had a break in the ice around 1990 and 1991 with the truth commission, but that hardly healed the country. If anything, it made it worse. It made it clear that people were tortured and were disappeared, but there was nothing you could do about it. In fact, the guy who was in charge of it was still commander in chief of the army because of the Constitution he wrote. Not only that, he became senator for life under his Constitution.

I went back to Chile in 1998, eight years after the fall of the dictatorship. I wrote a 10,000-word article saying that Pinochet was the historic victor because his economic model had been imposed. He was immune; everybody else was immune. There was no accountability. The whole world knew about this and it didn’t matter. Half of the Chileans had convinced themselves either that it was impossible to speak about it or wouldn’t speak about it. The other half had convinced themselves that being Chileans, they could not be bad people, and therefore there was no torture. If there was torture, it was because there’d been a war, even though one side had guns and the other side didn’t.

There must be a political, juridical recognition of that healing. People can heal individually at a certain point, but if the society does not accept responsibility for what it does, then the invented narrative is allowed to prevail. The old narrative that justified the torture continues to prevail unless you can institutionalize its reversal by saying, “No, in fact, we are not going to build the statue to this person because this person is now indictable for murder.” Things looked the darkest for me in 1998 when Pinochet became senator for life after stepping down from being the army’s commander in chief. There was a civilian government in power that was in its eighth year of power. Democracy had been restored. Not one military officer had been prosecuted in Chile.

In 1998, Pinochet was arrested by the British on a visit to see Margaret Thatcher.

The 501 days that Pinochet spent in British custody from October 1998 until the beginning of 2000 changed the entire political atmosphere in Chile. The invisible shield of impunity and an invincibility that had been created by him through terror, through a juridical system imposed by the military and by the complicity of many civilian political and journalistic organizations who did not have the courage to pierce that bubble of invincibility, was popped by the British detention.

When he arrived back in Chile, he was immediately indicted on charges of murder. He never completed a trial because of health reasons, but I don’t even think that mattered. Whether Pinochet goes to jail or not when he is 87 years old meant nothing at all. What mattered is that he was indicted and that as recently as last year, 30 some odd years after the fact, another 100 military officials and police officials were indicted for torturing and murder by the Chilean courts which are just starting to catch up. The importance is in having that political recognition. The personal thing is important, especially for the persons involved, but any ability to grow a new healthy generation cannot be achieved until society collectively accepts what it has done.

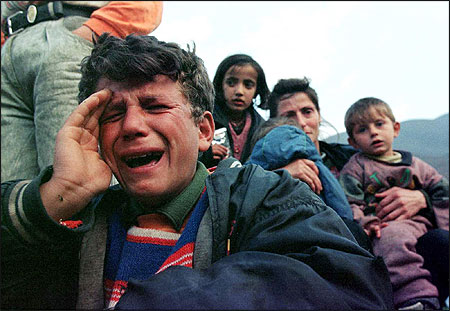

A refugee arrived in Albania in the spring of 1999 after being expelled by Serbian Army and police forces from his home in Kosovo. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.

Anna Di Lellio is the author of “The Battle of Kosovo” and editor of “The Case for Kosova: Passage to Independence,” a collection of essays on Kosovo’s history, politics and culture. She teaches in the graduate program in international relations at The New School university in New York City and at the Kosovo Institute of Journalism and Communication in Prishtina.

There is no intention on the part of any government in these countries to really be engaged in establishing and carrying on a truth commission facing the past. They’ve gone ahead, however, with collecting stories. Memories of violence and trauma are often the basis of narratives of origins and of loss and recovery, so we shouldn’t be surprised that people reach far back to the 17th century in the case of Kosovo, and with Serbia to the 14th century, to find the roots of the trouble they experience today. These narratives, both individual and collective, compete with one another and cannot be reconciled until there is a political solution to the conflict. Only after that can there be recognition of the shared humanity of the people who have been involved in the conflict. This is not the reality now in the Balkans or in Serbia, where there is no political solution. This means the conditions are not in place to carry on with the exercise of having such commissions.

Journalists should be aware that they are not just interviewers, not just recorders. They need to have a framework of reference which is historical and political because in modern conflicts, competing narratives are produced and supported by groups of individuals that produce a story line of the suffering, of the conflict, of their history and identity, and they try to impose it as the story line. Borrowing from the Argentinean sociologist Elizabeth Jelin, these are the “memory entrepreneurs.” Journalists should be aware of this. In these types of conflicts, there aren’t just two parts; there is also a shared history of colonialism and post-colonialism.

It’s been researched that many trauma symptoms subside after going through the testimonial process. We also see that giving testimony in different kinds of contexts, whether legal, artistic or as an oral history, provides a reason for survivors to tell their story that they may not find so quickly in the therapeutic sessions. In fact, many of the survivors I’ve worked with want and seek this kind of public forum for the recognition and as a form of redress. We see now many situations such as truth and reconciliation commissions, testimonies, archives, different contexts in which people are telling their stories. It is not just individual narration that is being developed, but it is collective narration.

Seamus Kelters is assistant news editor with the BBC Northern Ireland. He covered Belfast for 20 years, 16 of them with the BBC. He co-authored “Lost Lives,” chronicling the stories of men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles.

I and a lot of others grew up with a 40-year conflict with 3,700 people dead, 50,000 wounded, and at least 9,000 jailed. If that seems small-scale, it was. We received undue focus because we were white and spoke English. Conveniently on our doorsteps were television, print and radio newsrooms full of young journalists eager to cut their reporting teeth. Our Troubles, and that is what we called our conflict, received coverage, too.

People segregated for 400 years live at opposite ends of the same street. Along those fault lines of sectarian divide was always the angry noise of violence. When it spewed onto the streets again 40 years ago in August 1969, it was familiar to older people. We’d had our troubles before. Police shot my grandfather when he was 17 years old, and he was badly wounded. Another relative of mine was killed in Belfast in 1921 as he walked toward my grandmother; a sniper shot him in the head. I grew up with these stories.

The book, “Lost Lives,” grew out of that family memory. The details of the shooting recorded in the only book on the subject were wrong. Working as a print journalist, and with official and unofficial records and communal knowledge weathering, I realized that no matter how many funerals and bodies we covered, the most recent troubles would not be adequately recorded.

“Lost Lives” was squarely a work of journalism. In close to a million words, we attempted to record not just the names, but the detail of each person’s life and death to the fullest extent possible. Working chronologically, we recorded every fact we could test. We knew the work would cause pain. Although some credited “Lost Lives” with having contributed to the peace process, we never saw it as our job to make things better.

We cannot necessarily do justice to the dead. Ink isn’t blood, but as journalists our first duty was to the record. We became almost obsessed with facts, reality and truth as far as we could find it. As important as what we said was the way we said it. David McKittrick, one of my coauthors, was born in the Loyalist Shankill Road heartland. I came from the fiercely Republican Falls Road and we did most of the writing between us. Five of us though were working across the material and we needed a style guide. So each entry starts with three introductory lines; in those three lines we list the age, the victim’s name, date of death, marital status, number of children they had, religion and occupation.

We estimate there are 22,000 pieces of information in those first three lines alone before we get anywhere near the text where we wanted to write at length about each life and each death. What started as a simple advisory note mushroomed into a style guide which in itself was 50,000 words. Working and living in a divided society, to record that conflict we’d have to be respectful to the other side with our language and be aware of the sensitivities of victims’ relatives. Also, we had to be aware of the truth. In our book, which is close to a million words, unless it is within quotation marks, we don’t use the term “terrorist.” We don’t use the words “freedom fighter.”

Most controversial were the times when we were writing and we were inclusive. So the perpetrators can be found in the pages alongside the victims. We made no judgments of right or wrong. To some extent that was unnecessary in a place where so many of those are confirmed in the cradle. We didn’t spare facts, but we took other cares in our language. We had access to some coroners’ files, but we didn’t feel it appropriate to introduce pathological descriptions. The families of the dead, we felt, knew that all too graphically already and we did not need to pander to any voyeuristic darkness.

Most of our material came from newspaper combings. Some of it also originated with our own journalistic trusted sources and a few came from personal experience. I saw my first person shot dead when I was nine years old. Two years later, I helped to hold someone together after he’d been shot. Many of my primary school class joined the IRA. At least one was shot, several were killed, and I don’t know how many were jailed.

In the first edition of “Lost Lives,” we dedicated it to children that they might learn the lessons. Of all the journalists I know who have covered those troubles not one of them tells the stories to our children. So one of the things that I always take away from events like this and one of the points that I always make at home is how much better a journalist I would have been if I would have had this vocabulary 20 years or more ago when I was just starting. It is something that I think all of us can help young journalists with.

At the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication, Marc Cooper is a journalism professor, director of Annenberg Digital News, and associate director of the Institute for Justice and Journalism. His memoir of Chile, “Pinochet and Me,” describes his experiences as a translator for Chilean President Salvador Allende and his escape from Chile after the 1973 military coup.

Being in Chile during those 17 years of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship was a surreal experience. Everybody who wanted to know knew that people were being tortured and that they were being disappeared. There was no rule of law, only complete and arbitrary and unaccountable use of terror, but you could speak about it only under penalty of death, literally.

There was a truth commission in Chile that was established right at the time of Pinochet’s having lost his own plebiscite that he couldn’t rig properly. What was very upsetting about that was an amnesty law that he’d put into effect made it impossible to prosecute anybody who was found to have committed any of these crimes. We had a break in the ice around 1990 and 1991 with the truth commission, but that hardly healed the country. If anything, it made it worse. It made it clear that people were tortured and were disappeared, but there was nothing you could do about it. In fact, the guy who was in charge of it was still commander in chief of the army because of the Constitution he wrote. Not only that, he became senator for life under his Constitution.

I went back to Chile in 1998, eight years after the fall of the dictatorship. I wrote a 10,000-word article saying that Pinochet was the historic victor because his economic model had been imposed. He was immune; everybody else was immune. There was no accountability. The whole world knew about this and it didn’t matter. Half of the Chileans had convinced themselves either that it was impossible to speak about it or wouldn’t speak about it. The other half had convinced themselves that being Chileans, they could not be bad people, and therefore there was no torture. If there was torture, it was because there’d been a war, even though one side had guns and the other side didn’t.

There must be a political, juridical recognition of that healing. People can heal individually at a certain point, but if the society does not accept responsibility for what it does, then the invented narrative is allowed to prevail. The old narrative that justified the torture continues to prevail unless you can institutionalize its reversal by saying, “No, in fact, we are not going to build the statue to this person because this person is now indictable for murder.” Things looked the darkest for me in 1998 when Pinochet became senator for life after stepping down from being the army’s commander in chief. There was a civilian government in power that was in its eighth year of power. Democracy had been restored. Not one military officer had been prosecuted in Chile.

In 1998, Pinochet was arrested by the British on a visit to see Margaret Thatcher.

The 501 days that Pinochet spent in British custody from October 1998 until the beginning of 2000 changed the entire political atmosphere in Chile. The invisible shield of impunity and an invincibility that had been created by him through terror, through a juridical system imposed by the military and by the complicity of many civilian political and journalistic organizations who did not have the courage to pierce that bubble of invincibility, was popped by the British detention.

When he arrived back in Chile, he was immediately indicted on charges of murder. He never completed a trial because of health reasons, but I don’t even think that mattered. Whether Pinochet goes to jail or not when he is 87 years old meant nothing at all. What mattered is that he was indicted and that as recently as last year, 30 some odd years after the fact, another 100 military officials and police officials were indicted for torturing and murder by the Chilean courts which are just starting to catch up. The importance is in having that political recognition. The personal thing is important, especially for the persons involved, but any ability to grow a new healthy generation cannot be achieved until society collectively accepts what it has done.

A refugee arrived in Albania in the spring of 1999 after being expelled by Serbian Army and police forces from his home in Kosovo. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.

Anna Di Lellio is the author of “The Battle of Kosovo” and editor of “The Case for Kosova: Passage to Independence,” a collection of essays on Kosovo’s history, politics and culture. She teaches in the graduate program in international relations at The New School university in New York City and at the Kosovo Institute of Journalism and Communication in Prishtina.

There is no intention on the part of any government in these countries to really be engaged in establishing and carrying on a truth commission facing the past. They’ve gone ahead, however, with collecting stories. Memories of violence and trauma are often the basis of narratives of origins and of loss and recovery, so we shouldn’t be surprised that people reach far back to the 17th century in the case of Kosovo, and with Serbia to the 14th century, to find the roots of the trouble they experience today. These narratives, both individual and collective, compete with one another and cannot be reconciled until there is a political solution to the conflict. Only after that can there be recognition of the shared humanity of the people who have been involved in the conflict. This is not the reality now in the Balkans or in Serbia, where there is no political solution. This means the conditions are not in place to carry on with the exercise of having such commissions.

Journalists should be aware that they are not just interviewers, not just recorders. They need to have a framework of reference which is historical and political because in modern conflicts, competing narratives are produced and supported by groups of individuals that produce a story line of the suffering, of the conflict, of their history and identity, and they try to impose it as the story line. Borrowing from the Argentinean sociologist Elizabeth Jelin, these are the “memory entrepreneurs.” Journalists should be aware of this. In these types of conflicts, there aren’t just two parts; there is also a shared history of colonialism and post-colonialism.