The Facebook posting was striking, coming from a friend who writes powerfully about race and was now arguing against the University of Oklahoma’s expulsion of fraternity members for their racist chants. “Educational institutions ought to educate—or try to,” he wrote. “This was a teachable moment and should have been used to teach.”

Others weighed in, until one poster effectively shut down the debate. “Instead of dialing up the umbrage meter for a bunch of drunk and stupid college students … I wish people would get outraged—and do something about—things like this.” She linked to the tragic story of a teenage mother's search for justice following rape accusations. The discussion fell silent.

Is it possible to place stories on a universal scale of impact, import, or horror and assign coverage and empathy accordingly? These equivalency debates are the natural extension of trying to hold two or more events in balance, a primitive definition of what news editors do. When their work is good, there is a complex weave of decisions hidden beneath the surface of a news report.

But there is a pernicious quality to those equivalency arguments that suggest malevolent intent on the part of journalists and overlook more complex realities about newsgathering. As reporting resources contract and social media empower us all as arbiters, debates over where journalism aims its floodlights have grown more pitched.

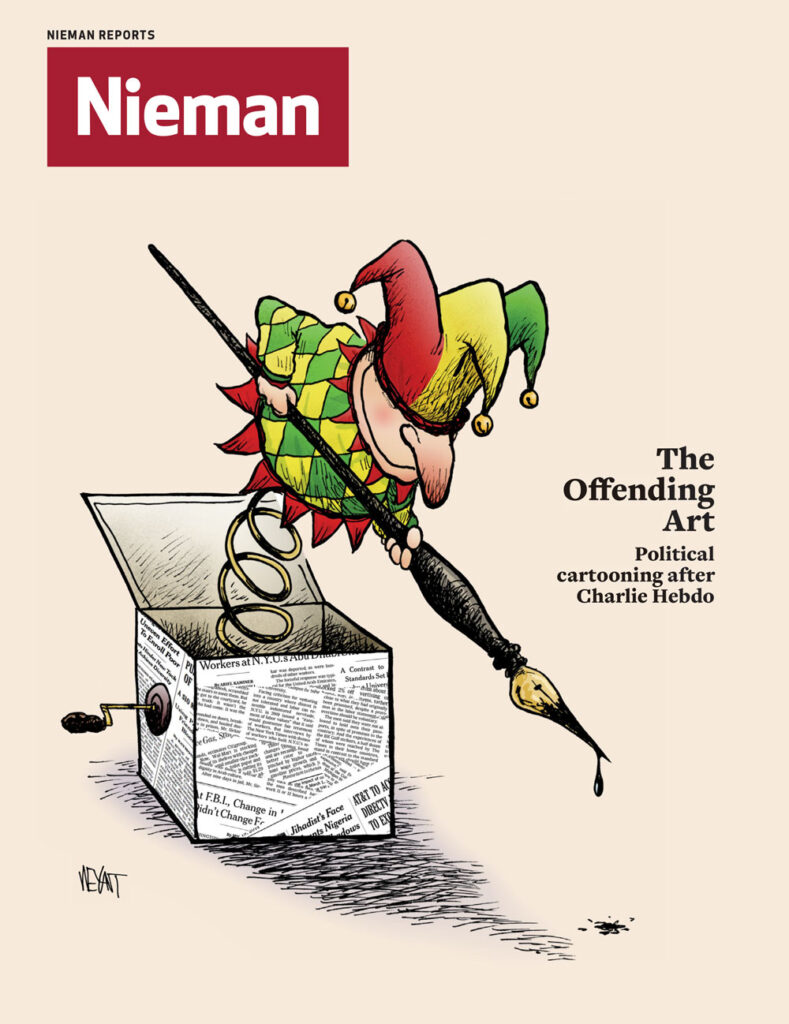

These questions took on an urgent quality following the Charlie Hebdo killings in Paris. Heavy coverage by Western media soon found critics: Why did that story—with 17 victims and three gunmen dead—receive more attention than Boko Haram’s murderous attack in Baga, Nigeria, with claims, according to the BBC, of between 150 and 2,000 dead? Some critics sought a discussion about the inherent differences in the stories. Others practiced ridicule, as evidenced by this tweet from a journalism professor: “US media on Baga: Hey, we just did Ebola. Isn’t there someone else to call?”

Why did two news stories need to compete, rather than stand on their own individual merits?

The equivalency battles rang hollow to me, with more emphasis on body count estimates than the larger news significance of either development. And why did the stories need to compete, rather than stand on their individual merits? I wanted to check my reflexes so I contacted the man whose Facebook account hosted the short-lived discussion about hate speech in Oklahoma: Don Wycliff, a wise journalist and critic who served as public editor of the Chicago Tribune, head of that paper’s editorial board, and writer for The New York Times editorial pages.

He said the discussion had troubled him, too, then parsed the criticism: The logistical differences of traveling to the stories that made for “huge differences in speed and depth of coverage.” The danger to reporters who enter the perimeters of Boko Haram’s power. The difference between a terrorist eruption and a civil war. How we report on a “principle”—freedom of expression—under murderous attack as opposed to ongoing coverage of “an appalling, mind-boggling disregard for the sanctity of human life.” The implied threat that the terror in Paris could be replicated in the U.S.

But what particularly troubled Wycliff about the equivalency criticism were two things the critics implied but did not state.

The first: That black lives are not valued in newsrooms the same as white lives. “There may be cases where this is true or where the facts suggest it, but Charlie Hebdo/Boko Haram was not one,” Wycliff wrote me. “If black lives were undervalued in the Boko Haram case, it was the Nigerian government that did the undervaluing.”

The second: The media is responsible for shining a light on Boko Haram sufficient to cause the world to intercede. “I think the critics vastly overstate the ability of the media to galvanize ‘the world,’” Wycliff wrote.

Reading Wycliff’s closing thought, I reflected on our last issue of Nieman Reports documenting the perilous conditions in which so many foreign correspondents work and the anemic support for their labor.

“That doesn’t relieve the media of the duty to report, to keep trying to make the relevant interesting,” he wrote, “but it does argue for some sobriety about what can be accomplished.”