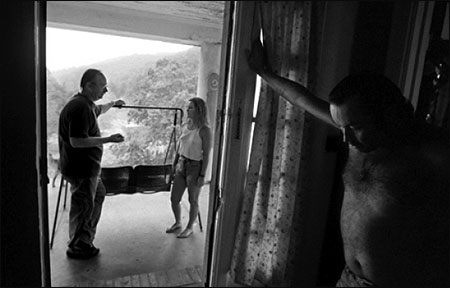

Gary Ball, a former coal miner (left), is now editor of the Mountain Citizen newspaper in Inez, Kentucky. Ball had recently written a story about this couple’s house.

Photos by Steve Mellon/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.Ask Americans over the age of 40 to close their eyes and visualize Appalachia, and they’ll most likely conjure one of the black and white news pictures to come out of the region in the 1960’s. The image they see will be perhaps a shoeless child standing on the porch of a squalid shack or a toothless man wearing tattered clothes. Those pictures had far-reaching and lasting power, a fact not lost on those who were photographed.

One morning in Inez, in the hills of eastern Kentucky, reporter Diana Nelson Jones and I walked into a diner, where a few locals were lingering over their morning coffee. When we introduced ourselves as journalists, one man shot out at us, “You going to make us look like a bunch of idiots, like those last reporters did?”

We were prepared for the question. In fact, Diana and I had discussed at length how to deal with the hostility of those weary of being portrayed as helpless, dumb and poor. We explained to the man our purpose: to explore the effects, if any, of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty which he declared in Inez in 1964. Then we told the man we’d do our best to avoid the stereotypes that had come to define his home.

Covering poverty is important, especially since our sometimes giddy coverage of the economy leaves the impression that everyone is getting rich. And coverage of this topic can also be a bit touchy. Some subjects see their poverty as an indication of failure; they want no part of reporters and photographers who want to make it news.

Tommy Fletcher may fall into that category. During his famous visit to eastern Kentucky, President Johnson visited Fletcher’s home, a shack-like structure pressed into a steep slope just outside Inez. Fletcher then was a poor man. He still is. His home looks much the same as it did in those old news pictures. Diana and I paid Fletcher a visit. It seemed fitting to go to the place where Johnson’s “War” began, but our visit was an awkward encounter. He mumbled answers to a handful of questions, then only reluctantly agreed to be photographed.

Back in Pittsburgh, after Diana and I had completed our work in Appalachia, I discussed with picture editor Pam Panchak the idea of leading with one of those pictures, juxtaposed with a historic photograph of Johnson’s visit to Fletcher’s home. The idea was quickly scrapped: it seemed to suggest only failure and continued poverty in Appalachia, and that certainly wasn’t what we’d found.

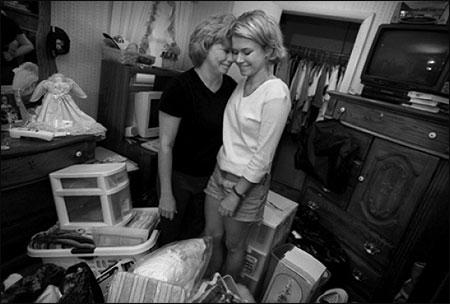

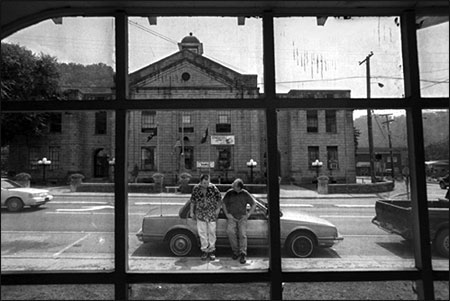

Instead, we narrowed our choice to a handful of pictures focusing on the incremental progress being made by individuals in the region. One was a photograph of Emma Fletcher (no relation to Tommy), a former welfare recipient who was helping her daughter pack for college. This picture suggested a universal theme—a parent’s desire to give her child a better life. We also considered a picture of Gary Ball, a former coal miner who’d become the local newspaper editor (in the process, his income dropped from $50,000 to $18,000). In the image, Ball leaned against his old car in downtown Inez and talked to his college-age son. It did not exude optimism, as did the Emma Fletcher image. Ball’s body language seemed tentative. Perhaps, we thought, this was a more appropriate picture to lead a story about a region making agonizingly slow progress.

Finally, we settled on a picture of Ball talking with a couple on the porch of an eastern Kentucky home. We felt this was the most complex image because it hinted at the poverty that still exists in Appalachia as well as at the wariness of outside influence and of change. The photograph also gave readers a sense of the region’s geography. There was some concern expressed that a shirtless man in the photograph simply reinforced stereotypes. But the man’s presence, off to one side and in fading, shadowy light, was, we decided, balanced by Ball, whose story represented Appalachia’s hopeful struggle into an uncertain future.

After leaving an abusive relationship and working her way off welfare and into a job, Emma Fletcher (left) was proud to be helping her daughter Melanie pack for college.

Gary Ball (right) talks with his 19-year-old son, Josh, near the Martin County courthouse. Like thousands of others, Ball has had to change careers after being laid off from his work in a coal mine. With few opportunities in the eastern Kentucky county, Josh will probably have to leave to find work.

Steve Mellon is a photographer at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.