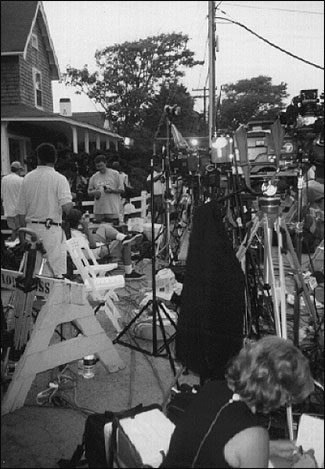

Huge TV trucks parked near the Hyannis Port pier to transmit words and images to the world. Photo by Melissa Ludtke.

When I was a child, President Kennedy and his family lived nearby. In the summer, I could always tell it was Friday night by the sound and sight of a fire engine roaring down the street to prepare for the President’s arrival. I knew that in a few minutes the helicopter carrying him would touch down on the lawn outside his parent’s house. Many times, even if my dinner was on the table, I’d head out the door and run down the street so I could be there when he arrived.

Sometimes the President would toss a football to children gathered behind the short white picket fence that marked the closest spot from which we were allowed to watch. Or as he came up the private road he’d be driving a golf cart loaded with kids from his extended family and we’d run alongside as they went to the candy store a block away.

I can remember that as a child these moments seemed special, even on those occasions when all we did was watch his helicopter touch down.

This past July, when that President’s son, along with his wife and sister-in-law, died on their way to this destination, this short white picket fence again became the boundary for those who wanted to witness what was happening at the other end of this small private road.

This time, however, those who came to bear witness arrived not on bicycles or foot. These witnesses arrived in huge trucks displaying enormous satellite dishes and towering antennas. Out of the trucks came portable video cameras with powerful telephoto lenses, and big fat microphones, and miles of colored wires that followed the human occupants like snakes as they found their way to a spot at the side of the short white picket fence.

In all, about 50 of these giant trucks set up business on the narrow streets of this village, their engines humming loudly and their lights blaring brightly as days kept turning into nights. Their size made it difficult for the people who lived in this village to pass by. And along the short white picket fence, hundreds of people with badges dangling from around their necks to signify membership in the community of journalists kept 24-hour-a-day vigils as they waited for something to happen at the other end of this road.

On Sunday afternoon, the day after the plane disappeared, my usual midafternoon walk to the pier unearthed another cluster of cameras, lights and microphones. Dug in on the beach—as close as it was possible for them to be to this private pier—were people holding video cameras jockeying for spots with photographers dangling multiple cameras, some with lenses that must have been as long as my arm. As I walked back from the end of the pier, I could not avoid staring into this sea of cameras and imagining what it must feel like when they are raised in unison and their loud clicking motor drives switched on as photographers strained to get “the picture.”

It didn’t take long for me to see the results of this pier-side vigil. Back in my living room, on the TV, was video of several members of the Kennedy family walking up the pier, their heads down, eyes averted from the cameras, returning from a sail. The next day newspapers had photos from the walk. I am not sure what any of this told any of us except perhaps that these family members were sad.

And so it went in Hyannis Port for nearly a week while news directors and editors back home decided there would be news emanating from this road. But what “news” would their on-site reporters find here when family members made it abundantly clear that grieving would be done in private? From early on, it should have been apparent that there would be no personal testimonials recorded near this short white picket fence. And when word did come from the family, the statement was widely circulated by Senator Kennedy’s office. If there was news to be had about the rescue-turned-recovery operation, then that information was going to surface about 20 miles away, where the National Transportation Safety Board and Coast Guard held briefings to explain what their search was revealing.

But still the cameras, producers and revolving cast of on-air “talent” remained next to the short white picket fence, now crowded behind police barricades on a public street that their presence made impassable. Network news “stars” came and went so they, too, could use, as a backdrop for their words, this silent road where Kennedy homes now had window shades drawn against spying eyes of telephoto lenses.

Impressive as this technology might be that can transport an audience directly to a scene such as this, if what viewers take away are impressions from reporters who have no news to impart, then is having this technology reason enough to use it and pretend its product is news? Or are pictures of Kennedy homes, and occasionally their occupants coming and going in cars or gathering for a private mass under a tent in their yard, enough in this era of celebrity journalism to qualify as an emerging definition of “news”? Or is the unquestioned commercial success of instantaneous voyeurism enough to convince reporters that “the people’s right to know” (or more accurately these days, “the people’s right to see”) always trumps “the individual’s right to privacy”?

In her book, “The Right to Privacy,” (co-authored with Ellen Alderman) Caroline Kennedy helps us to at least understand what it is that we, as journalists, pit our Constitutional right to free speech against when stories such as this one surface. In her book she writes about a Harvard Law Review article, written by Louis D. Brandeis and Samuel D. Warren. It put forth a revolutionary legal concept, the origins of which were prompted by Warren’s outrage when details from a family wedding appeared in the gossip columns. The arguments these two men set forth, Kennedy informs us, are credited with creating “the right to privacy,” a legal right that can be used in state courts but should never be confused with any Constitutional right. Warren and Brandeis defined their new legal term as “the right to be let alone.”

Prophetically, what these two men worried about in this article as the 19th Century was ending has come to pass during the 20th. Society, they warned, would become more complex and technology more intrusive and, as these two things occurred, the need to protect individual privacy would become even more urgent.

Certainly this is so. We feel it in every aspect of our lives. We are concerned when we hear about someone’s financial and medical records landing in unscrupulous hands. Or when we learn that private messages sent electronically have been read by a strange set of eyes. Or when someone steals from us words spoken on a telephone. These circumstances alert us to the fact that something we might not have realized was so precious might be in the process of being taken away.

Maintaining what is personal as private is becoming one of the huge challenges each of us faces as technological advances threaten to obliterate walls that once seemed secure around us. And this challenge exists as well for those of us whose job it is to record the events of our time and convey images and news about them back to viewers and readers. Part of having the freedoms we do—those rights that the press in this country should and do possess—means that professional judgment should be applied so that we demonstrate wisdom and responsibility in protecting the precious from what can, too quickly, turn pernicious.

Writing in Nieman Reports in 1948, the First Amendment scholar Zechariah Chafee said, “The press is a sort of wild animal in our midst—restless, gigantic, always seeking new ways to use its strength.” Responding to those words nearly 50 years later, Caroline Kennedy writes, “When the [press] uses its strength to uncover government corruption or lay bare a public lie, it is the country’s watchdog. But when the animal roams into our cherished private sphere, it seems to turn dangerous and predatory. Then we, Americans, turn on the press. We want a free press, we say, but not that free.”

Americans already inform pollsters that they are turning on the press. Trust in it is eroding. Even journalists, when asked, reply that standards are slipping. In a 1999 survey by the Committee of Concerned Journalists, more than two-thirds of the journalists queried described as a “valid criticism” the belief that there has been serious erosion of the boundary between reporting and commentary. Most members of the press agree, however, that what distinguishes their profession is its contribution to society, its ability to provide “people with information they need,” according to the Committee’s report.

But in today’s marketplace—where news competition comes from cable upstarts which have no journalistic heritage and management at every station keeps watchful eyes on the news department’s bottom line—working journalists privately lament news decisions, but follow orders to set up camp at places like the short white picket fence. Then they talk, even when they have no information to pass along that people need to know.

Nevertheless, the bosses back home are heartened when ratings come in. People watched, the numbers tell them, in greater volume than might ever have been imagined. Switch away from this scene, with its quiet backdrop of ocean and the occasional glimpses of famous, sad faces, and viewers turn to find similar images somewhere else. Such was the lesson once again learned during that week’s coverage.

Yet not everyone thinks that this lesson, taught by numbers, is the one most essential for news executives to learn. Letter writers to The Boston Globe provided a different teaching tool. “It is now time for the media to leave the famous compound,” one observed. “There is no news there to be had. Repair the damage, depart the grounds, leave the Kennedys alone. Their private moments, now and forever, are by definition not newsworthy.” Another correspondent linked blame to cause: “The networks will hide behind the people’s right-to-know argument, but the truth is that they have exploited a tragic accident for their own benefit. And why should we be surprised?… For them, it’s just another sensational day at the office.” And a third wrote, “According to the press, there is a vested public interest in camping out en masse in front of the Kennedy family home and in using telephoto lenses to capture private moments.”

So how is it that journalists who care about what they want to be and do can reconcile what their profession might be becoming in its willingness to quench the public’s thirst for celebrity and do so in the name of “news?” Clearly, individual journalists, when faced with such an assignment and bills to pay at home, are unlikely to argue that “news” lies elsewhere and that is where they want to be. For each one who might try, 10 others would be on their way to the short white picket fence to take his or her place.

Perhaps the way to reconcile the unpleasant but seemingly mandatory encampments of the press is to work harder to separate in this coverage what can accurately be called news from all that is otherwise broadcast. For lack of a better term, call it “entertainment.” For despite its portrayal of sadness, in a strange way that is exactly what the media’s visual intrusion into private mourning has become. And at those many moments when there is nothing to say, resist the urge to talk and, consequently, say nothing. As poet Andrei Codrescu observed on “Nightline” on Monday evening of that week, “Yes, I’m sad, but I wish they, we, could just be quiet.”

And quiet it was at the other end of that road in Hyannis Port until one morning when the sound of a helicopter could be heard as it prepared to descend onto the lawn in front of that home where the President’s landed nearly four decades ago. Suddenly, video cameras were turned on and the satellite dishes on trucks to which they were tethered were put into action. Reporters jockeyed for position so they could talk as the helicopter landed behind them. Soon Senator Kennedy and his sons were walking across the lawn and into the helicopter and as quickly as it had come, it was gone.

But where was it going? Why had it come? Reporters near the short white picket fence didn’t know. But that absence of knowledge didn’t stop them from talking, turning speculation into what during this week had been, too often, confused with news. On one local station, journalists seeing this image from Hyannis Port sparred mildly over the exact nature of this trip. Later, after reporters made calls to verify information, we’d be told that this was taking the President’s brother and nephews to the place where they’d be given the body of his son.

One mourner in New York told a TV interviewer, “The media brought us into their family.” Certainly that is true. Arguably, no family has as skillfully employed the media as a way to communicate ideas and shape their legacy. And out of that use surfaces awareness that there might be, at times, a price to be paid in return, a price that might involve loss of privacy and an exploitation of their images. And throughout this week, that seemed a price that this family knew that it was paying, even as they found ways—with a burial at sea, a private memorial mass—to restore some of the protective walls that all of us should be wary of taking down. For, in the end, these walls protect us all.

Members of the press set up camp next to the short white picket fence. Photo by Melissa Ludtke.

Melissa Ludtke is Editor of Nieman Reports and a 1992 Nieman Fellow. Her book, “On Own Own: Unmarried Motherhood in America,” was published in paperback this year by University of California Press.