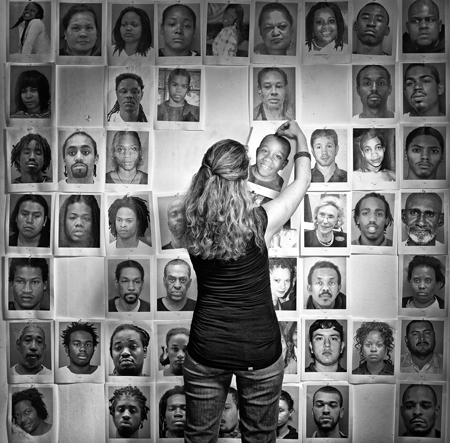

Photo by Douglas Sonders

There’s an energy to big, busy newsrooms that’s unlike any other. Reporters and editors tapping away on keyboards, muttering through copy, interviews taking place, police scanners crackling, photographers running out to a story, or back in to file before deadline. Within that noise is a sense not that something is about to happen, but that something is happening. That the world is moving and we are moving in it and there is news.

This is probably what I missed the most when I turned my kitchen into a one-person newsroom three years ago. In the mornings, after clearing away the breakfast dishes, I would set up my laptop on the kitchen table and log into WordPress. My mission as founder of Homicide Watch D.C. was simple: to mark every murder death, remember every victim, and follow every case. I wanted to provide comprehensive fact-based reporting on every homicide in my city, the type of reporting the local newsrooms weren’t doing.

I’d pitched editors on this project before making it a solo-run. Their responses were that the community wasn’t interested, that there wasn’t a business model for crime coverage, that resources were already spread too thin, that covering every homicide, crime to conviction, was impossible.

I disagreed. I was watching families of murder victims and suspects try to share information about cases on Facebook and online obituaries. I was watching them organize vigils and court hearings. I saw that those most loosely connected to the crimes—the neighbors, teachers, coworkers—were often left behind, struggling to find accurate information and, without this, unable to find any understanding in the tragedy. These people, my neighbors, my community, deserved more.

I remember thinking often in those first weeks how calm my new quasi-office was. There weren’t any editors calling out for copy, colleagues shouting into phones, or Boy Scout troops touring the office. The keyboard of one computer makes little noise compared to the keyboards of dozens, hundreds.

Months later, when Homicide Watch D.C. won the Knight Award for Public Service Journalism at the Online News Association conference in San Francisco, while so many applauded so loudly, I thought about the quiet in which this project started. I placed the trophy firmly on the podium. “For all the people working from their kitchen table,” I said, “this one’s for you.”

I’m a journalist. I believe in journalism, and I believe in our communities. I believe in holding those in power accountable. I believe in building civic knowledge. I believe in celebrating the good and trying to understand and solve the bad. But mostly I believe in storytelling. In the power of stories to validate who we are, how we live our lives, and our experiences, and the power of stories to allow us to enter into a communion with our communities, sharing who we are, and perhaps together, becoming who we would hope to be.

This is what journalism does.

Which is not the same thing as saying that this is what big media organizations always do. But it is also certainly true that everyday people, with an Internet connection and a blogging platform, are able to hold those in power accountable, build civic knowledge, celebrate the good, understand and solve the bad, tell our stories, and change our worlds.

There is no inherent honor in being big or small. And I don’t consider it a personal failing or triumph that Homicide Watch D.C. was launched in the quiet of my kitchen instead of the chaos of the newsroom. In fact, when I think about size, it’s not the staffing or office space that I think about at all, but rather impact. Here, I think, Homicide Watch hits in the big leagues.

Stories have the ability to change who we are, and I measure the success of Homicide Watch D.C. by the strength of the community the site has affected. I think of the families that comfort one another online. I think of the friends who live far away and stay in touch with a case by following it online. I think of the suspects’ families, unable to talk about what they’re experiencing with their families and friends, turning to the Homicide Watch community. And I think of one young man, who sat down with detectives for questioning on a case and said, “Naw man, I ain’t killed nobody. I seen HW. They lockin’ people up for that shit now.”

The detective told me about this the next day, and we laughed a little together at the silliness of this idea that this kid suddenly knew that people were being arrested for murder in D.C., and that he’d seen it on Homicide Watch. But I actually take this very seriously.

I don’t know this kid and I don’t know if he was ultimately arrested in any case. I don’t know if he had a gun or a knife or if he used it. I like to think that perhaps he didn’t, that he’d seen the stories of those involved in homicides in D.C., of the victims and the suspects, and his reality had changed. That he was able to change who he wanted to be and that night to not draw his knife or his gun but say, ‘I can’t kill nobody. I’ve seen Homicide Watch. They lockin’ people up for that shit now.’

There is nothing as big, or as small, as an individual person, whether that person is a young man thinking about committing a crime, a journalist working from a kitchen table, or an editor calling out for copy in the middle of a large newsroom. Whether I’m working alone, or in one of those big busy newsrooms, I hope to always remember this.

Laura Amico, a 2013 Nieman Fellow, is the founder of Homicide Watch D.C.