Julia Reynolds , a criminal justice reporter for The Monterey County (Calif.) Herald and 2009 Nieman Fellow, moderated this panel presentation about the intersection of investigative journalism and trauma. She led off by offering this observation:

Investigative reporting definitely has its own challenges with trauma; it’s an even more intense immersion than many other kinds of reporting because you can stick with a story day after day, sometimes year after year. If you’re an obsessive kind of person, there can be personal damage by only focusing on one thing, and sometimes it’s a terrible thing that you’re thinking about. It might be con-artist sociopaths or businesses or institutions that are abusing power. Whatever it is, it can take its own toll in terms of personal trauma on journalists. Often we cover other people’s trauma as we try to find people who are victims of anything from financial scams to abusive governments.

Miles Moffeit is an investigative reporter with The Denver Post who has reported on social justice and corruption issues that have led to government reform and criminal prosecutions. His most recent project exposed how police mishandled DNA samples nationwide and he went on to chronicle what happened to Tim Masters, the first man in Colorado freed by DNA evidence from a life sentence, after he left prison. In his talk at the “Aftermath” conference, Moffeit described his approach to investigating the incidents of rape at the Air Force Academy.

With every project, a reporter needs to find the people who understand the culture, the emotional landscape, whether it’s a psychiatrist or the spiritual leaders or anybody who sort of orbits that community.

When I tried to think about the military, I needed to know how to connect with these victims. So I immediately went to the rape crisis center that sat next to the Air Force Academy and had a long conversation with a woman who opened her door at midnight to these cadets who were allegedly raped. And she was able to explain to me that this had been going on for years, that women who came to her crisis center never got justice, and the statistics really bore out. There were like 60 accusations and zero convictions, and she was really frank with me. She said, “As a man, you’re going to have difficulty connecting with these women. You may need a third party in the room and a woman to go with you into these interviews.” And so we developed sort of this long-term strategy.

Listen as Moffeit recounts the ways he—and a female colleague from the Post—went about interviewing women who were alleged victims of rape. After hearing one woman tell of running back to the barracks after she was raped, he tried to put himself in “that person’s path” as a way of trying to understand how she’d felt. “And I asked her during our next session, ‘So what did it feel like running back to the barracks and, you know, wearing your military boots?’ And she said, ‘They’d never felt heavier on my feet.’ And that line alone was really powerful.”

"The Days After" was a recipient of the 2006 Dart Award for Excellence in Reporting on Victims of Violence for newspaper reporting. Arnessa Garrett has been a journalist at both large metros and community dailies for more than 15 years. She’s a senior editor of news at The Daily Advertiser, a community newspaper in her hometown of Lafayette, Louisiana, where she directs local coverage of courts, crime and natural disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. She’s been the lead editor on several of the paper’s investigative projects, including “The Days After,” a special report on domestic violence. Edited excerpts follow of her observations about how editors work with reporters on long-form, investigative stories involving trauma.

Investigative journalism today is also about telling a compelling story, in addition to looking through documents and creating databases. Because of this, journalists who cover violence and trauma have to draw upon a wide range of skills; while delving into a person’s often tragic story, broader issues of justice and injustice and inequities in public policy that can provide context to your readers need to be kept in mind. But journalists who cover trauma don’t always come with that investigative skill set.

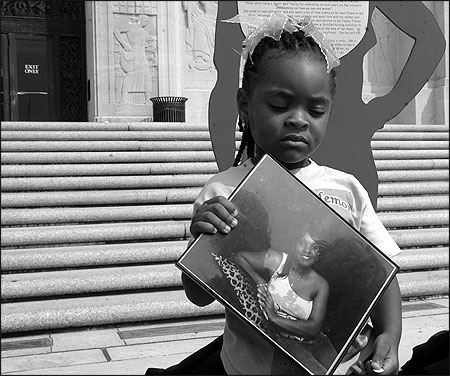

At a small newspaper, the night cops reporter is often the youngest, most inexperienced reporter on the beat; they’re the ones usually sent to talk to mothers who’ve lost their children, to victims of fires, floods, car accidents. So for editors who work with these reporters, it’s important for us to push not only for the story that happens in that moment but what happens in the aftermath of violence and tragedy.

In the daily news cycle, it’s easy to forget victims because after one tragedy happens, the next one is on your doorstep. But if we listen to the victims, we can give our audience a deeper understanding of issues that matter to our communities and issues that you can’t convey in drive-by journalism. And as we talk about newspapers and journalism facing difficult economic times, we see over and over again it’s those kinds of stories that our readers are demanding from us. There is an audience for these stories. And, as an editor, I’ve realized that the best stories come from reporters who are out in the field. That’s where your best ideas are going to come from, rather than someone sitting in an office telling a reporter to go investigate something.

I do listen to my reporters at our community paper. Like many cops reporters, ours work on a constant treadmill of covering car accidents, shootings and stabbings. But in my six years there, the best cops reporters have always managed to find time to stop amid the daily coverage to recognize the larger trends that need to be exposed.

Listen as Garrett describes the genesis of the paper’s long-term domestic violence project. It began as an idea from a reporter and photographer after a man killed his ex-girlfriend at her apartment in view of many, including the paper’s photographer, and then killed himself in a local church.

I asked them as an editor would and not in a way that diminished their idea, but I really wanted to press them for what was new about what we had to say about domestic violence. They had the idea of following every domestic arrest for a year in our city, seeing how long it took for the arrest to make it through the court system. For several months, we refined that idea and developed it into this project. From looking at this one family’s tragedy, the project broadened to put a spotlight on how police and prosecutors deal with victims of violence in our community.

Garrett shares in more detail several tips based on what she learned in this project. Among these tips are the following:

- First, do no harm: Victims of trauma are under so much stress … give them the opportunity to reconsider [being involved in a story] and to say no. There’s no story, I believe, that’s worth harming an innocent human being, and this person has already suffered so much.

- Be persistent: While I say this—and this may seem contradictory—if you are pursuing a story about a victim of trauma and you’re passionate about the story, be persistent.

In talking about persistence, Garrett describes how a woman initially backed away from being involved with the project, but over time—with connections to her maintained by the reporters—she changed her mind.

- Double-check reporting: Victims of trauma are processing their experience. Don’t assume they’ll remember all the details accurately. At the most basic level, everybody double-checks your reporting.

- Demonstrate patience: Trauma victims are not going to be aware of every interview or photo shoot you schedule.

- Shop for an editor: If you are doing this kind of work, you’re going to need an editor who cares about the project as much as you do; you’re going to need somebody just to process your own feelings as you’re going through this whole project.

- Numbers do matter: I like a good narrative, but what elevates a trauma story to the next level is the context, and trauma reporting is strengthened by investigative techniques. I think readers want to be told why this person’s tragedy matters on a large scale. And in trauma journalism especially, investigation can help shed light on ways to avert tragedies.

We like to do stories about victims because they tend to be sympathetic. But I think we serve an important role when we tell stories of victims who are not so sympathetic. After Katrina, we did reporting on what happened to prison inmates who were transported from the Orleans Parish Prison to our local jail, and they had horrific stories. They didn’t know whether family members were dead or alive or if they had a home. They had no way of contacting anyone because they had evacuated to other areas. We ran that story and, as you can imagine, the reader response was, “So what—they’re in jail.” That was discouraging, but I still think it was one of the best pieces that we ran after Katrina. It’s hard, but the challenge is there to write stories when the perpetrator is sometimes the victim.

Paul McEnroe is an investigative reporter at the (Minneapolis) Star Tribune with a focus on social justice issues. He’s been a national correspondent for the paper and has covered international events, including the Gulf War, the war in Bosnia-Croatia, and the Iraq War. In 2008, he received a one-year fellowship with the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma. He began his presentation by speaking about people who were mentally ill and institutionalized and whose names he doesn’t know but whose information he has in records identifying them only by numbers. Edited excerpts from his remarks follow:

How do you find your voice as a reporter to speak on behalf of those that have no voice? That was my great dilemma. One day I got in my car and just started driving. I was trying to sort all of this out. I found myself going through southern Minnesota, and I ended up at a prison that had been the state hospital for the feeble-minded, the derogatory term they used. I parked my car and saw this barbed wire and razor wire. It occurred to me that this is what prison is like for people who couldn’t speak.

I started walking on rolling hills with beautiful autumn colors. It was about 65 degrees at four o’clock in the afternoon, and I’m walking by myself to an area that’s probably as big as this courtyard. I look through the tall grass and leaves and I see plaques. No, they’re not plaques. These are stones, and then they’re not stones. Wait a second. They’re not stones, they’re plaques—what are they?

And all of a sudden it came to me. These people were people, but they were not seen as people. They were the most vulnerable people in our society who had been stripped of everything including their name. In some binary system of bureaucratic hell, they’d been given a list of letters and numbers; they didn’t even know their name. And it all came to me. As with any good investigative reporting, there’s the need for physicality—a physical effort that has to take place to be able to successfully complete the story for the reader, the viewer, and the listener. Good editors will always want reporters to explain what they heard. What did it sound it like? Smell like? How did it make you feel? When you drove home, what were you thinking about? Did you turn the radio on to try to not think about it? Or did you just drive home in silence and really let it wash over you? There has to be a physicality to our effort; when we do that, the story grows exponentially.

I started seeing these people in a completely different vein. At one point I must have had files of 40 or 50 different people—men, women and children—in my briefcase, and if I was stuck at a traffic light, I’d just pull out a file and start reading. And I would get to know these people as if they weren’t numbers but they were a Peter or Michele, Deidre. I got to know them as if they were alive. They were friends, neighbors and my colleagues at work. The closer I felt to these people, the more attention I paid to details—to timelines, to chronologies, to what kind of food they ate, what kind of medication they were on, and at what time they’d done something.

So when we talk about narrative arc—the presentation of the problem, the conflict, the meaning, the character development—one thing that’s missing in that writing formula is if you’re not emotionally tied into people whom you’re writing about. You need to plug into your emotional partnership with the people.

Listen as Paul McEnroe describes how he wrote about an institutionalized mentally retarded woman, Elaine Kleinschmidt, by digging into a thick folder containing fragments of her life and emerging with succinct paragraphs about her. He uses this as a teaching exercise with his students. His instructions: “Here’s this report. It’s this thick. Write four paragraphs on it.”