On a cold winter's night, a few minutes after 6 p.m., police in Rapid City, South Dakota were called to a house in the Lakota Community Homes development where Allen Locke and his family were living. Locke, 30, was drunk, his wife said, and she wanted him out of the house until he sobered up.

The responding officer, Anthony Meirose, found Locke on the kitchen floor. As Locke stood up, the officer noticed a steak knife in his hand. Meirose told investigators that he heard Locke say “It’s a good day to die,” and that he ordered Locke several times to drop the knife, according to a report from the South Dakota Division of Criminal investigation (DCI). When he didn’t, Meirose fired five shots at him. Locke was pronounced dead at the hospital. The South Dakota DCI determined that Locke had lunged at the officer, though his wife says she witnessed the incident and disputes this. No charges were filed against Meirose.

The killing of Allen Locke on that cold night just before Christmas in 2014 got little attention outside Rapid City. Nor, in the year or so since, has there been much widespread coverage of the killings of Paul Castaway, shot in Denver in July by police who said he was threatening his mother, though she argues that deadly force was unnecessary in this incident; William J. Dick III, a 28-year-old suspected armed robber who died in Washington State after a U.S. Forest Service agent shocked him with a Taser; or Larry Kobuk, 33, who died after being restrained by officers booking him into the Anchorage Correctional Complex on charges that he stole a car and drove it with a suspended license.

All of these people were Native Americans.

The day before his death, Locke, a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe of Pine Ridge, and about 100 other people took part in a march in Rapid City calling for better treatment by police of Native Americans. “Hands up. Don’t shoot,” the protesters chanted under gray skies and in chilly temperatures. There is, one speaker at the rally said, “an undeclared race war here in South Dakota.”

Police kill Native Americans at almost the same rate as African-Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Between 1999 and 2013, an average of .29 per 100,000 Native Americans were killed by police, compared to .3 per 100,000 for blacks and .11 per 100,000 for whites. “America should be aware of this,” argues Chase Iron Eyes, a lawyer and a leader of the Lakota People’s Law Project, which runs a publicity campaign called Native Lives Matter. But for the most part, America is not aware of this.

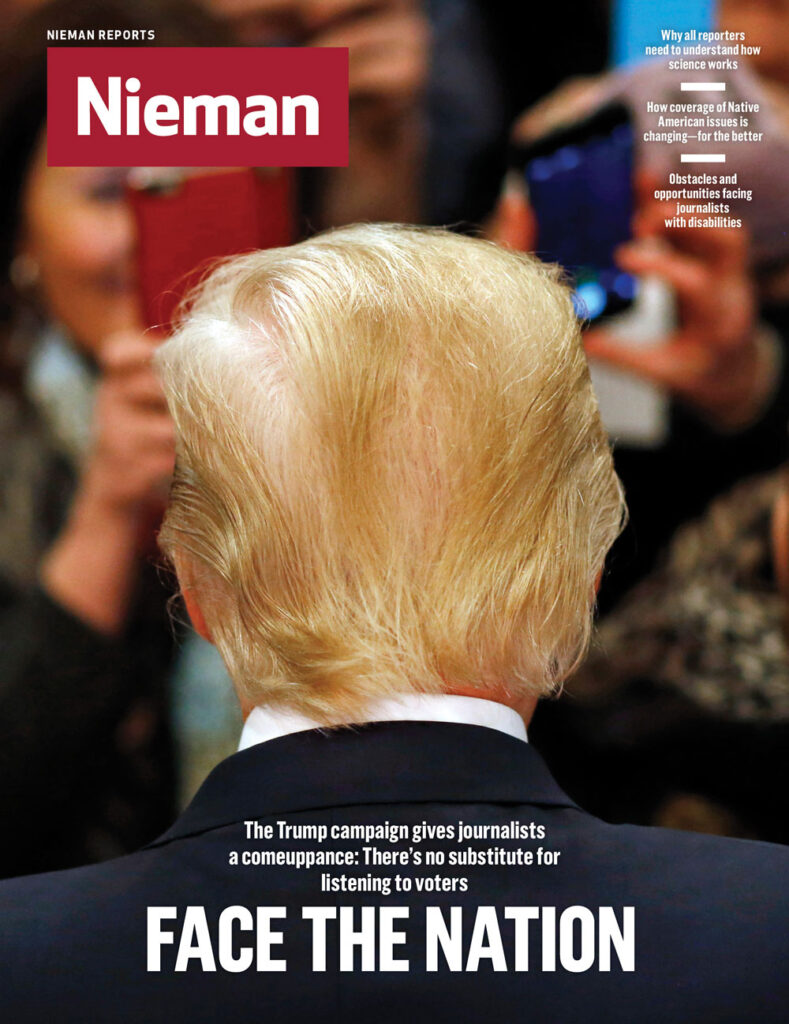

That may be changing, albeit slowly, as both mainstream media and Native American-run digital outlets begin to cover American Indian issues more robustly.

In some ways, Native American cultures are worlds unto themselves, but increasingly they are part of bigger issues that transcend their borders. Take energy, especially with the extensive drilling of oil on Native American land in North Dakota and elsewhere. National energy issues are Native American issues, too. There is an urgent need for more investigative reporting on Native American issues, but such projects are hampered by a lack of press freedoms on Native American lands and a shortage of journalists―Native American and otherwise―who understand the culture as well as the politics and legal intricacies of Native American life, says Mary Hudetz, a former president of the Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) and the former editor of Native Peoples magazine.

Native American cultures increasingly are part of bigger issues that transcend their borders

Stories that mention Native Americans remain comparatively rare, according to Christopher Josey, who conducted research on this topic as a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois. His 2010 review of the top 20 Internet news sites by traffic, from The Daily Beast to The New York Times, found that Native Americans accounted for .6 percent of the people portrayed in news coverage on those sites, though Census figures show that the 5.2 million Native Americans make up 1.7 percent of the U.S. population. When they were mentioned in stories, Josey says, Native Americans were often portrayed in stereotypical situations—as the owners of and workers in casinos, for example. “By neglecting them in coverage and showing them in stereotypical ways when they do,” he says, “news media are communicating that Native Americans are not a vital part of the national conversation on race.”

There is plenty of bad news to report. The exploitation and oppression experienced by Native Americans has translated into incontrovertible health, psychological, economic, and social challenges. Native American men are imprisoned at more than four times the rate of white men, and Native American women over six times as often as white women, according to a 2009 report from the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. (Black men are imprisoned at nearly six times the rate of white men and black women at four times the rate of white women.)

CDC data paint a bleak picture for Native Americans. Sixteen percent of Native Americans—their Census designation is “American Indians,” and most advocates say both terms are acceptable—have diabetes, the highest rate of any U.S. ethnic or racial group. The incidence of alcohol-related deaths is three times that of the broader population. The rate of drug-induced death is the highest of any minority group. Native Americans are more likely to experience sexual assault. And, according to Census data, about 25 percent live in poverty, compared to 15 percent of the general population. Native Americans’ high school dropout rate in 2012, the last year for which the figure is available, was more than double the average—14.6 percent compared to 6.6 percent across all races—the Department of Education reported last year. The unemployment rate for Native Americans who don’t live on tribal lands is roughly double the national average, at 11 percent in 2014, also the most recent period for which the information is available from the Labor Department.

One reason Native issues get so little attention is that editors worry about retelling the same old story about poverty, alcohol, and drugs on reservations, says Scott Gillespie, editorial page editor at the (Minneapolis) Star Tribune. Many Native Americans, in turn, mistrust journalists, tired of the “poverty porn” they say depicts the places in which they live as all but hopeless. The setting for these stories is often the Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the nation’s poorest, where mortality, depression, alcoholism, drug abuse, diabetes, and other problems are prevalent. “There’s the idea that you’re perpetuating that story line,” Gillespie says. “That isn’t helping anybody, and I think it might be one of the things keeping editors from saying, ‘Let’s go do it.’”

Still, some news outlets are pushing to address crucial Native issues. Pacific Standard, published by the nonprofit Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy, ran an investigation into sexual violence against Native American women in the booming oil towns of North Dakota. ProPublica has reported on how Native Americans living on a North Dakota reservation may have been cheated out of money for oil rights. Kaiser Health News covered how Native American health services are benefiting from the Affordable Care Act. Student journalists at the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University reported on the exploitation of Native Americans by payday lenders, a project for which they received an Investigative Reporters and Editors Award. Cronkite News, a service of the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, has produced more than 70 stories relating to Native Americans since 2011, one of which, about potential commercial development on Navajo Nation land in the Grand Canyon, was picked up by PBS NewsHour. Mic.com, a website aimed at millennials that claims 22 million monthly readers, is among the handful of outlets that have reported on the high rate of killings by police of Native Americans.

The Washington Post’s award-winning series about injustice on Native American lands and the (Minneapolis) Star Tribune’s editorials outlining the deplorable condition of many federally-funded reservation schools demonstrate the challenges of covering Native issues.

The impetus for the seven-part Washington Post series on crimes—including domestic violence and sexual assault—against Native Americans in Alaska, Arizona, and the Dakotas came from conversations with criminal justice experts. “Someone said to me, ‘No one’s writing about what’s going on with Native Americans,’” says reporter Sari Horwitz, whose beat is the US Justice Department. “It’s hard to get interest in a newsroom for stories that most people don’t feel affect them. Native Americans and Native American issues are invisible in this country.”

Horwitz persuaded her editors to let her do these stories, in part, by making the argument that they were about a compelling subject outside the usual Beltway bubble. More than a quarter of Native American woman have been the victims of rape or attempted rape and almost half have experienced some other sexual violence—slightly more than the average for women in the U.S.—according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. A 2008 report submitted to the Justice Department found that two-thirds of female Native Americans who were the victims of rape or sexual assault described their perpetrators as white or African-American—many of whom would therefore go unpunished because up until March 2015 tribal courts couldn’t prosecute non-Natives. (Tribal courts can now try non-Natives for crimes of sexual violence thanks to the Violence Against Women Act.) Covering the Native American community in depth requires resources that are in shorter and shorter supply—time, money, and patience. Newspapers rarely will give journalists months off for special projects.

For many reporters, getting their news organizations to back ambitious stories about Native Americans is only half the battle. The other half, they say, is gaining the trust of their subjects—especially for white journalists who come to reservations as strangers. “The trust issue was a huge one,” Horwitz recalls. “I am basically another white female journalist calling and saying, ‘I want to come and study you.’ There have been so many studies and so many efforts to figure out what’s going on, and this is just one more person coming, and then nothing changes.” People on reservations are reluctant to talk about taboo subjects like sexual abuse and suicide, while bad experiences with outsiders in general—and journalists, in particular—make many suspicious. “People feel like they’ve been lied to before and promised things that didn’t happen,” says Star Tribune editorial page editor Gillespie.

Horwitz’s breakthrough came when she found a Native American woman, a victim of sexual abuse, who had become an activist and knew that sharing stories in a paper like the Post could help get people to care about these issues. “It was freezing cold,” Horwitz remembers. “I sat at her kitchen table, and she told me a story about how her mother had been sexually abused, how she had been sexually abused, how her daughter had been raped. She started telling me all these different stories about the legacy of boarding schools and how that had led to so much sexual abuse on reservations. Each story led to the next one.” As the stories in the series started to appear, other Native Americans began to trust Horwitz, too.

Gillespie’s colleague at the Star Tribune, Jill Burcum, faced similar challenges when she began work on what would ultimately become a series of editorials called “Separate and Unequal,” about the abysmal conditions of under-heated, sparsely equipped tribal schools, at least one of which was infested with rodents. Burcum had one thing going for her, though: some experience on reservations, since she’d covered the story of a 16-year-old who killed nine people and injured five on a shooting spree at the Red Lake Reservation in 2005. Native Americans “feel—fairly, I think—that we parachute in, often in tragic situations, or come up to document problems that reflect poorly on them,” Burcum says. “They feel, not wrongly, that we’re there for our benefit, and then we go away. So why would you open up your home to a journalist or talk to them?”

Reporters from the outside have to find a trusted person who will advocate for them

In these circumstances, Burcum says, reporters from the outside have to find a trusted person on the reservation who will advocate for them. For Burcum, it was the school superintendent. “You have to have a sponsor, and the superintendent acted in that capacity for us,” she says. “We were sort of under her wing. People felt that they could talk to us.”

Burcum and her photographer took other steps to gain their sources’ confidence. They spent hours at one school over five or six visits, each requiring a four-and-a-half-hour drive each way. They stayed in a hotel on the reservation, part of a tribal casino, where they got to know the hotel staff. They made sure to eat at tribal restaurants and shop in tribal stores. They tipped well. Burcum even sometimes brought along the harp she plays. “Then they kind of remembered me,” she says. “It was part of letting people know that you’re a real person. By being there and me having my crazy little personality quirks, we set ourselves apart.” Finally, she says, “People felt that they could talk to us.”

The series of editorials was published at the end of 2014 and was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. In response, the Minnesota legislature increased state funding for Native American education. Burcum testified before a congressional committee about the problems at reservation schools. The series remains prominent on the newspaper’s website. “We’ll keep it there until the problem’s solved,” Gillespie says.

As for her sources on the reservations, Burcum says, she thinks they feel progress has been made, “but they’ve been around long enough to know that things don’t change that quickly.” In April, US Rep. John Kline, R-Minnesota and chairman of the House Education and Workforce Committee, visited one of the schools spotlighted by the series, and so did Burcum. Her reception then was vastly different from the first time she’d set foot on the reservation: “I got hugs from the tribal elders. The kids were glad to see me. The teachers stay in touch.”

Instead of focusing on unemployment, which is more than 50 percent in some tribal areas, the Native News Project at the University of Montana School of Journalism looked at the entrepreneurial businesses people started to earn money, from a tribal ranch on the Fort Peck reservation to a flower and coffee shop on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation to an electronics manufacturing business on the Flathead Reservation. “We’re not necessarily focusing on the shadows and the sadness,” says Jason Begay, a Navajo who grew up on a reservation and runs the Native News Project, “but on how people are persevering.” Other Native News Project stories have examined sexual and gender identity among Native youth, how Christianity and Native traditions coexist on a Crow reservation, and the possible impact on Native populations of the legalization of marijuana.

Many Native Americans applaud this approach. “We are really struggling to find ways to change the narratives in our communities, that we’re lifting ourselves up, and we need others to work with us on that,” says Jacqueline Pata, part of the Tlingit tribe and executive director of the National Congress of American Indians. “My concerns have always been, and continue to be, about balance.”

More balanced coverage, argues Mark Trahant, a member of the Shoshone tribe and former editorial-page editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer whose Trahant Reports covers Native American issues, would include pieces about the Alaska Native Medical Center (ANMC). The ANMC focuses on services to prevent illness and has achieved impressive outcomes, including a 40 percent reduction in emergency room visits and a more than 35 percent decrease in admissions, despite historic health disparities between Native Americans and other groups. “It does amazing, innovative work at far less cost, and yet it’s uncovered,” he says. “That amazes me.”

There are only 118 Native American journalists working at U.S. dailies—less than 1 percent of all newsroom employees

Tristan Ahtone, a member of the Kiowa tribe of Oklahoma who often reported for Al Jazeera America, won a following among Native Americans and others for writing about new topics, such as how one tribe is invoking treaty rights to stop another oil pipeline, the rethinking of the militant American Indian Movement that grew up alongside the Black Panthers in the 1960s, and an international indigenous basketball tournament. His approach: “Stop looking at Indian Country as a foreign place with foreign people doing foreign things. It keeps us apart from each other, and reinforces the idea that these people are different, that they’re victims, that they’re helpless. They get covered when there’s doom, gloom, or there’s blood. The cumulative effect is that you’ve got communities that are isolated from the rest of the country and generally distrustful of journalists, and that just creates a continuing cycle.”

Ahtone is one of only a handful of Native American journalists. There are 118 self-identified Indian journalists working at U.S. daily newspapers, according to 2015 data from the American Society of News Editors. That’s .36 percent of all U.S. newsroom employees. Native American activists say there need to be more newsroom internships and training programs for aspiring Native American journalists. Hudetz says the NAJA’s summer internship program, established in 2014, has already made a difference. At least six of the 10 college students who participated that first summer have gone on to a journalism internship or graduate studies in journalism. “Native students don't always get what they need in a college journalism program,” Hudetz says, “or they might need some mentors on the outside who can support their education from afar and who understand and appreciate their cultural heritage. Without that, they don't feel supported, and they don't pursue it, and they feel discouraged.”

“Native media content creators are establishing themselves and could function as the eyes and ears on the ground in partnership with mainstream media,” says Iron Eyes of the Lakota People’s Law Project. “We just need to build those bridges so the people in the mainstream know what’s going on.”

Journalists in the mainstream need to do their part, too, Trahant says: “I don’t think new media is ever going to replace what a national network could do. On its worst day, a network newscast still has an audience bloggers only dream about. When the mainstream does something, it still matters.” And when it doesn’t, says Horwitz, “Those stories float away.”

Native American News Outlets

A sampling of websites that offer news and commentary on Native American issues

Indian Country Today Media Network

A national platform for Native voices and issues, Indian Country Today is a news service owned by the Oneida Nation of New York, with coverage of breaking news, politics, arts and entertainment, business, education, and health.

Indianz.com

A product of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska and Noble Savage Media, a Native American-owned media firm, this website posts a mix of original news reporting and aggregated reports about subjects relevant throughout Indian Country.

National Native News

Funded in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, National Native News is a headline news radio program, providing listeners with timely coverage on local and international current events relevant to Native American and indigenous communities. Distributed by Native Voice One, the distribution division of Alaska-based Koahnic Broadcast Corportation, the radio show can be heard online and on radio stations across the U.S. and Canada.

Native America Calling

A production of Koahnic Broadcast Corporation, a Native-operated media center, this live call-in program is streamed online and broadcast on nearly 70 public, community, and tribal radio stations in North America, bringing callers in conversation with experts and guests about a wide range of issues of interest to Native communities.

Native Appropriations

Founded by Adrienne Keene, a member of the Cherokee tribe and an assistant professor of American Studies at Brown University, Native Appropriations is a blog highlighting the misrepresentations of, and racial insensitivities toward, Native peoples in mainstream culture.

Native Health News Alliance

An independent nonprofit news organization launched in partnership with the Native American Journalists Association, Native Health News Alliance produces multimedia news and feature stories focused on the health and wellness needs, issues, and concerns of Native communities and their governments. Media outlets that register with NHNA can republish the organization’s articles for free.

Native News Project

Reported, written, photographed, and edited by journalism students at the University of Montana, the Native News Project features long-form stories from Montana’s seven reservations, each intertwined by a single topic of importance to the state’s Native population. In 2015, the theme was “Intertwined: Stories of Detachment and Connection from Montana’s Reservations,” which explores relationships binding people to each other and to their tribes.

Native Sun News

A weekly newspaper based in Rapid City, South Dakota, the Native Sun News covers local news and events around the Northern Plains region, which includes the Pine Ridge Reservation. Its “Voices of the People” section also features editorials and opinion pieces on national issues that affect Indian Country.

Trahant Reports

Mark Trahant, University of North Dakota journalism professor and former editorial page editor for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, posts news about Federal Indian policy, health care reform, and elections. He also writes a number of opinion columns reprinted by outlets such as the Indian Country Today Media Network and High Country News.

— Eryn M. Carlson, Jon Marcus, and Jonathan Seitz