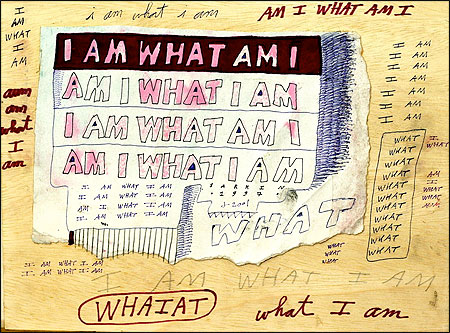

“What I Am” by Jon Sarkin, whose transformation from mild-mannered chiropractor to frenetic artist Amy Ellis Nutt chronicled in her 2011 book.

There is nothing normal about my journalism career—I landed my first newspaper job at 42—or my book-writing career. In a former long-ago life as a sports reporter, I coauthored a golf book/memoir for a woman on the professional tour and it hit the remainder bin faster than a two-foot gimme hits the bottom of the cup. So after a 13-year hiatus and a move from Sports Illustrated to The Star-Ledger of Newark, New Jersey—you get the upside-down idea, right?—I had some trepidation about embarking on a second book.

As it does for most newspaper reporters who write books, my unanticipated journey started with an article. Back in 2003 I'd met Jon Sarkin, the subject of "Shadows Bright as Glass: The Remarkable Story of One Man's Journey From Brain Trauma to Artistic Triumph." Actually, first I met his art. I was in New York City interviewing neurologist Todd Feinberg for a major story I was writing on science's search for the origin of consciousness. Questions about identity and mind have always interested me and, in fact, prompted me to go to graduate school in philosophy. (It was escaping the PhD dissertation that sent me on my circuitous route to journalism.)

On the wall of Feinberg's office I noticed a fascinating and colorful picture and asked him about it. The abstract drawing of a series of 1950's Cadillac tailfins was clever and deeply intriguing. So the doctor then told me the tale of Sarkin, a man who had contacted Feinberg by phone a year earlier after hearing him interviewed on NPR. At the time, Feinberg had just written his first book, "Altered Egos: How the Brain Creates the Self," in which he chronicled his work with stroke patients who have suffered identity disorders. Sarkin asked Feinberg if he could somehow explain what had happened to him.

In 1988, Sarkin was a successful young chiropractor. On a crisp autumn day in October, he was standing on the eighth tee of a golf course not far from his home in Gloucester, Massachusetts when something shifted inside his brain. The experience wasn't painful, but it was terrifying and within days Sarkin began experiencing tinnitus, a ringing in the ear. It steadily grew worse, and then every sound became magnified until even the crackling of eggs in a frying pan was enough to send him cowering under the bedcovers. He went to every doctor, every specialist, he could find, including chiropractors, audiologists, psychiatrists and neurologists. The best advice anyone could offer was that he use a white-noise machine. One doctor, however, suggested he might want to try a controversial operation with a brain surgeon in Pittsburgh. Sarkin did, but within hours of the operation he suffered a massive stroke.

Weeks later, when he came out of his semi-coma, Sarkin was a different man both physically and psychologically. The greatest change was in his personality. A calm, even shy, serious medical professional was suddenly loud, abrasive and completely uninhibited. Whatever was on his mind came out his mouth. After rehabilitation, when he learned to walk, talk and dress himself again, Sarkin went home. That's when the drawing started—spontaneously and prodigiously. He drew on magazines, on scraps of paper, on the basement walls, even on his cane. And the more he drew, the more obsessed he became with creating art. Primitive drawings of cartoonish figures eventually became dense, complex art pieces, and he expanded from impulsive drawing to large-scale portraits, collages and even abstract landscapes.

When I learned that Sarkin was a native of New Jersey and was about to have his first major New York City art show at the Diane von Furstenberg Studio, I knew I had to write about him for The Star-Ledger. We hit it off, and I wrote what was little more than a biographical sketch for the newspaper's features section.

Short Feature to Book Proposal

Sarkin and I kept in touch, and it would be a while before people would say, "Hey, this is a book." Eventually we realized they were right. But there was a problem. He'd already sold the rights to his life story to Tom Cruise and Paula Wagner, then at Paramount Pictures. As it turned out, the book rights were tied in with the film rights and it took close to five years of on-again, off-again efforts to clarify that contract before the green light was given.

Finally, in 2008, when I was writing what would become a 40-page book proposal, I realized so much had happened to Sarkin since I'd first written about him that I should do a longer piece for the newspaper. My editors at The Star-Ledger agreed. So this is how my short feature—after a break of a few years—got transformed into a book proposal, then re-reported as a newspaper series, and finally became a book. By the time the series, "The Accidental Artist," was published in the paper, I had a book contract from Free Press. For that series, I was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Feature Writing in 2009. I didn't win, but being a finalist helped to solidify support at the publisher, a division of Simon & Schuster.

During the next year I worked with a marvelous editor there, Emily Loose. Although I had very little contact with her during the writing itself, she was a terrific hands-on word editor after I handed in the manuscript. I didn't disagree with a single suggestion. My only disagreement was with the publisher's marketing department, which didn't like the title, "The Accidental Artist." People would think I was writing about art, they argued. The way I saw things, this is what a subtitle is for. Despite my best efforts (through Loose) to convince them otherwise, my backup, "Shadows Bright as Glass," a line from poet Wallace Stevens, emerged as the book's title. (Its subtitle is "The Remarkable Story of One Man's Journey From Brain Trauma to Artistic Triumph.") Nearly everyone I asked agreed that "The Accidental Artist" was better.

Making a Book

The Star-Ledger's series of stories, which consisted of a number of key scenes from Sarkin's life, was very different from the book proposal. My book agent, Wendy Strothman, kept urging me to expand the story beyond the tale of one man's unusual brain trauma. The wider the story's scope, the larger its prospective audience and the greater the chance would be of selling the book—to the publisher and then to readers.

Easier said than done, and doing this meant thinking differently. How could I connect Sarkin's experience to a larger theme? What could I contribute—that hadn't been said already—about this theme? Ideas percolated, as my agent pushed me away from straight biography and tugged me toward telling parallel stories about a man's search for himself and the story of science's search for the self.

This became a book I wanted to write, and it seemed like one that wouldn't be too hard to figure out how to write. I was correct about the first assumption, and way off on the second.

Trying to weave together two divergent strands—the narrative of a man's life with details of science writing and history about brain research—proved enormously challenging. In fact, I found nothing was harder than trying to mesh these two stories. When I handed the first draft in to my editor—a month early—I felt pretty good about what I had written, but not great. I'd actually handed in just 50,000 words and would have another 30,000 to write, although I naively didn't realize it at the time.

Turns out I was about to encounter the hurdles of length and style and voice that lots of reporters-turned-book writers trip over the first time around the track. My editor pointed me toward places where I needed to add or extend scenes. Good advice, relatively easy to execute. Getting my writer's voice to work well was harder. My reporter's training had put me in an objective frame of mind so I was using quotes and selecting words in ways that made my book's storytelling sound stilted and formal.

That needed to be fixed, and once again, my editor offered guidance by reminding me that I had to insert myself more into the book, not as a character, but as an interpreter of events and people. And loosen up as a writer, she counseled me. Be more expansive—even philosophical. This hint turned out to be what I needed to stitch chapters together seamlessly, though not easily. All of this was part of creating a "narrative arc," the two words that most terrify journalists who decide to become authors.

After thousands of hours and hundreds of pages of drafts, I embraced my fear, even if I still haven't embraced my book's title.

Amy Ellis Nutt, a 2005 Nieman Fellow, is a writer with The Star-Ledger in Newark, New Jersey. She was awarded the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing for her "deeply probing story"—"The Wreck of the Lady Mary"—about the sinking of a commercial fishing boat. On the day the Pulitzers were announced, her book "Shadow Bright as Glass" had just been published and Terry Gross's interview on "Fresh Air" with her and Jon Sarkin was broadcast that afternoon.