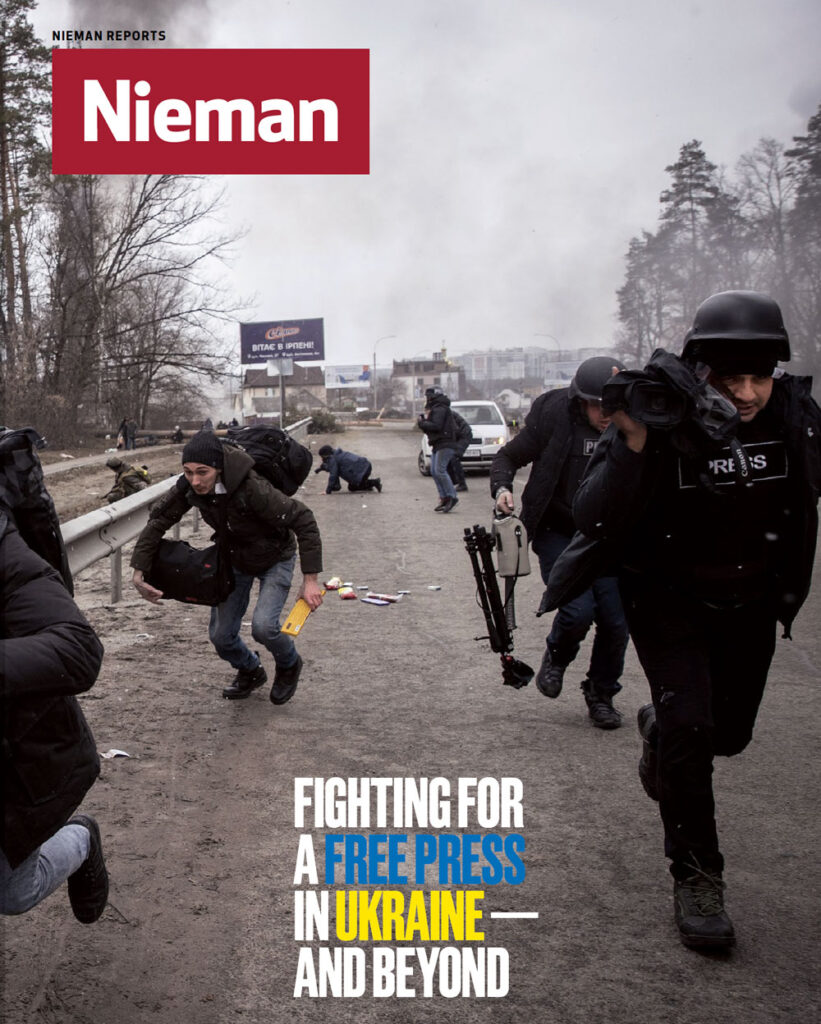

Four years later, the photo is a somber artifact. Two weeks into the war on Ukraine, Brent was shot and killed in an ambush outside Irpin, where he was working on a documentary about refugees. Visual journalism, so dependent on proximity, carries heightened risk during conflict. In a haunting reminder, the framed picture above Brent’s left shoulder, of Santa talking to American troops, was made by Anja Niedringhaus, another Nieman Fellow killed on assignment, shot at close range in 2014 by a police officer in Afghanistan. “Where once reporters and photographers were seen as the impartial eyes and ears of crucial information,” the AP said in announcing her death, “today they are often targets.”

Fearless. Ballsy. Badass. Certain descriptions of Brent in the days following his death offered caricatures of conflict journalists and obscured the man many of us knew. They didn’t capture his kindness and humility, or the humanity that was a hallmark of his work, whether documenting heroin addicts in New York or the Arkansas National Guard in Iraq. “Thoughtful stories about disenfranchised people” was how he described his mission.

There are tropes about conflict reporters that can camouflage the real reasons this young war has already killed seven journalists, injured 11, and claimed six as victims of kidnapping. From the indiscriminate attacks on civilians that also endanger reporters to the Russian government’s successful campaign to snuff out the last of the country’s independent press, it’s clear that Vladimir Putin presents the greatest danger to journalism in the region. “The Putin regime,” wrote Ukrainian journalist Katerina Sergatskova in Nieman Reports, “doesn’t want eyewitnesses.”

Brent did take risks in pursuit of stories, something he said he downplayed during his career out of concern it would sound boastful. In a 2013 interview with Filmmaker magazine he describes one trip to Mexico and Guatemala where “a soldier held a 9mm pistol to my head while another attempted to dangle me off the side of an ancient pyramid.” The reward he sought for his calculated risks was a deeper story.

“It’s a game of percentages,” his brother and documentary partner Craig Renaud explained in that same interview, “and even in the most dangerous places on earth your chances of survival are really high, and if you have a little extra experience with negotiating roadblocks, negotiating with warlords, and knowing where to stand when things get hairy, you really can do the job fairly safely. If we did not believe that we wouldn’t do it.”

Photographer Juan Arredondo, a Nieman classmate of Brent’s who was wounded in the ambush in Ukraine and eventually evacuated to the U.S., told me that he rejects the old “distorted, romanticized image” of photographers personified by the late Robert Capa and long encouraged by an industry that rewarded inexperienced freelancers building their careers in hot spots. “The idea that you would give your life for a photo—no, absolutely not. If anything, in my photography I want to celebrate life and the human condition.”

He said: “Maybe some want to celebrate him as dying for his bravery, but the Brent I knew was very shy, very smart, and very thoughtful. He was not going out there to try his luck. Everything was planned, every day assessing what we were doing and whether it was worth doing. There was none of that being a cowboy out there.”

Samantha Appleton, an experienced conflict photographer who was also a member of Brent’s Nieman class, believes she understands why he wanted to make his way into Irpin for a documentary about refugees. “The very heart of this story is the moment a person decides (or is physically forced) to leave their home,” she wrote to me. “Brent must have known he needed visual evidence of that decision itself. All he needed was one minute of footage but probably knew it was critical for the film … It is that last 2% effort that makes a photo story or documentary really strike hard. It's also why visual journalists are more often the ones killed (not because they are macho or stupid). It's because we always sit in the front seat of a car. We stay on the street while writers go back to file. It's just the nature of visual journalism: You only file what you are close enough to see and capture in a frame at the exact moment it happens.”

She added, “I have so many questions for him. But this is my best guess.”

The first time I met Brent, he described periods of excruciating shyness growing up in Little Rock, Arkansas. Fearful of speaking to people he met, he devised a strategy he called “mayor-for-a-day,” which required him to start a conversation with everyone he encountered, the way he imagined a mayor might. “I freaked out the guy at Starbucks,” he recalled and laughed. Listening was easier. He was obsessed with television news and transfixed by stories from around a world mired in the Cold War. His mother bought him a shortwave radio so that at night he could hear the BBC.

The day Brent died, I gathered with his grieving Nieman classmates on Zoom. Mattia Ferraresi, managing editor of the Italian newspaper Domani, said something that unlocked a part of Brent and made me question some of my own values. He recalled Brent telling him, “‘You’ve got to love what you report on’ challenging the principle that you need to keep a distance from your subjects to report fairly. Brent was all about empathy. He believed he had to really enter your life to really tell your story.”

I think Brent knew we thought he was special. “The best of us,” I told his grieving family. But what made him so was not derring-do. It was his almost religious commitment to stand witness, to the fundamentals of reporting, to the power of telling someone’s story close up. There was an inevitability about Brent. He couldn’t not do what he did.

At the end of his Nieman year, I gave him a novel, “All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr. In the book a French girl, blinded as a child, navigates the dangers of the German occupation through memory and her heightened powers of touch and perception, patiently making meaning out of chaos.

“You are very brave,” a young German soldier tells her.

“But it is not bravery; I have no choice,” she replies. “I wake up and live my life. Don't you do the same?”