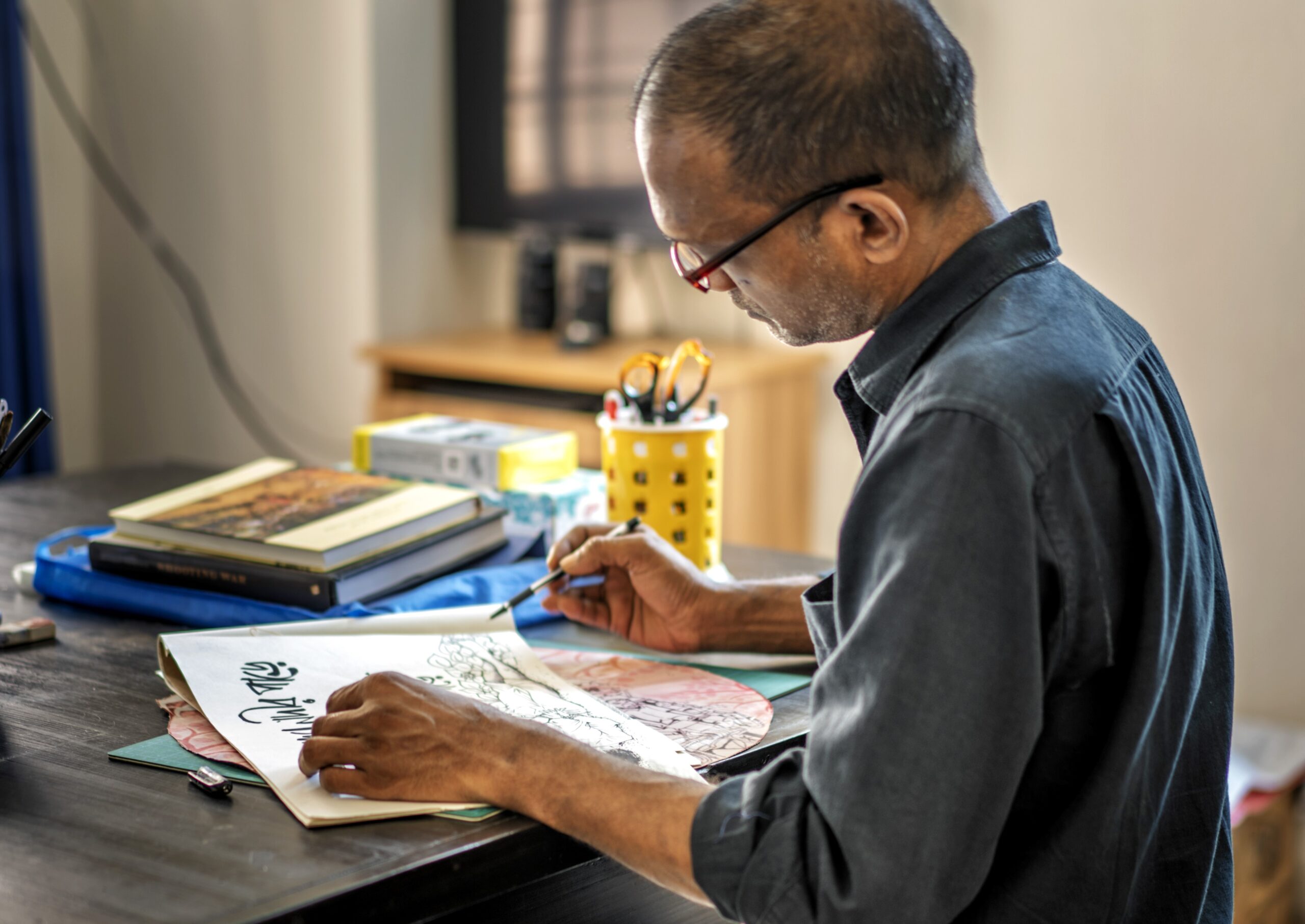

Ahmed Kabir Kishore remembers the hot, humid afternoon in 2020 when his long career as a political cartoonist was violently interrupted. He had dozed off in his apartment in Dhaka, Bangladesh, despite the noise from market shoppers outside his window, buying snacks to break the Ramadan fast.

Kishore, jolted awake by a banging at his door, opened it to find plainclothes officers — some brandishing weapons — shouting orders at him. They placed a hood over his head, dragged him by force to a waiting vehicle, and turned up the music to drown out his screams.

He was held for days in an undisclosed location and suffered severe beatings that left him with permanent hearing loss. Kishore was relentlessly questioned about each of his political cartoons as his interrogators screened them one by one with a projector.

“They found all of my cartoons satirical. I drew a lot of cartoons about coronavirus that time,” Kishore recounted to the Bangladeshi newspaper Prothom Alo. “They showed me a number of cartoons and asked, ‘Why were these drawn?’ and ‘Who are the people those caricatures represent?’”

He was eventually transferred to jail and had charges filed against him by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), an elite unit within Bangladeshi law enforcement that was sanctioned in December 2021 by the United States under the Global Magnitsky Act for human rights violations. Kishore was charged using a then-new law being wielded against journalists: the Digital Security Act, or DSA, which was renamed the Cyber Security Act in 2023.

“Ahmed Kabir Kishore identified himself as a cartoonist who has a huge fan following on social media,” read the charges. The list of alleged offenses included “spreading rumors and slander by drawing cartoons on current events,” for drawings mocking the government’s Covid-19 response and criticizing members of Bangladesh’s ruling party for not providing enough food, supplies, and medical care to the most vulnerable.

Kishore — although not the only political cartoonist in Bangladesh to be arrested and face trial — was the first charged under the DSA, which critics say is used to silence dissent. By some estimates more than 450 journalists have been charged since 2018 with offenses like tarnishing the image of the prime minister, her family, and other ruling party members. Dozens have been sentenced to prison. Three journalists were murdered in 2023 with little effort put into finding their killers, and the Committee to Protect Journalists noted that nearly 20 journalists were either harassed or attacked by members of the ruling party while reporting on voting irregularities during the Jan. 7 national elections. (The elections were boycotted by the major opposition parties and criticized by the United Nations, and western governments including the United States.) Even the handful of independent media organizations that try to report critically on politics and policy can’t completely divest themselves from government influence. (They are also no longer invited to the prime minister’s press conferences.)

The crackdown has had a chilling effect on the entire media industry in a country that has seen its standing on the Reporters Without Borders Freedom Index fall from 127th in 2010 to 165th in 2024. This dynamic has been especially unsparing for political cartoonists, who have a long and storied history in Bangladesh because of their role in denouncing colonialism and galvanizing support for independence from Pakistan. Some, like Kishore, who faces up to 14 years if convicted, have fled the country and now live in exile. (His case was postponed until July 2024.) Others have simply stopped drawing, their livelihoods upended by what the international community sees as an increasingly authoritarian government.

“It is more challenging now. People are less tolerant, and the Digital Security Act is holding many of us back,” said Shishir Bhattacharya, Bangladesh’s most well-known political cartoonist. “You can't draw with the tension brewing in your head that you may land in jail anytime and spend the rest of your life there.”

Bhattacharya, who rose to fame during the rule of military-chief-turned-politician Hussain Muhammad Ershad, started his own career in the 1980s by drawing political cartoons in college poking fun at the regime. His work, once widely and routinely published in newspapers and magazines, remained popular — despite criticizing the military rule — under several subsequent administrations. Even if the military regime shut down a particular newspaper, cartoonists could often find another place to publish his drawings.

That was until laws like DSA came into effect, Bhattacharya says, threatening free expression and having a chilling, self-censoring effect on news outlets.

“I experienced a bit of non-cooperation from the mainstream media,” Bhattacharya said. "They started requesting me to tame the drawings.”

The repression began a few years after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina took office in 2008 after challenging the military-backed government on a platform of strengthening democratic rule. Since then, Hasina has been reelected three times, and her political party, the Awami League, has used the legal system to thwart the opposition, tightening control and consolidating power. (According to one estimate, more than four million legal cases have been filed against members of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party in recent years.) Over time, the crackdown on dissent seeped into the independent press, and newspaper editors became more cautious both with investigative reporting and cartoons. That gave way to more restrictive legislation like the DSA, according to human rights activist Rezaur Rahman Lenin.

“The persistent retaliation against journalists covering political policies, purported corruption, and illegal business practices in Bangladesh under the harsh Digital Security Act is deeply troubling,” Lenin said. “With a vaguely defined ‘threat,’ the act permits warrantless arrests based on mere suspicion that a crime has been committed online, and it allows for hefty fines and jail terms for those who disagree.”

“The democratic space has significantly shrunk over the years,” said Sajjad Sharif, executive editor of Prothom Alo, Bangladesh’s largest newspaper, whose own editor, Matiur Rahman, is facing charges of damaging the image and reputation of the state under the DSA.

Sharif, whose career in journalism has spanned more than three decades, said newspapers in the 1990s used to routinely publish political cartoons attacking corruption and bad government policy on the front page. “We enjoyed freedom of the press,” Sharif said. “We ran some really good stories that we can’t think of publishing now.”

Gradually, those political cartoons disappeared from the front page. Although papers still run them occasionally, they lack the incisive bite they once had because the current media environment is hemmed in by the constant threat of prison time.

Political cartoonists are a particular target, critics say, because the medium has played such an important role throughout the region’s history because the visuals could reach mass audiences. Such cartoons often flourished in turbulent times, according to Robayet Ferdous, a journalism professor at the University of Dhaka, and were published in papers both large and small.

“In most cases, cartoons were so powerful that we could easily understand the editorial stand of the newspaper. It was a powerful as well as a popular medium to reach the audience,” Ferdous said. “I feel sad that the culture of publishing political cartoons is now at the end of the rope.”

Political cartoonists are a particular target, critics say, because the medium has played such an important role throughout the region’s history because the visuals could reach mass audiences.

The roots of political cartooning in the country go as far back as the late 19th century in Bengal, portions of which are now modern Bangladesh. But it was with the Great Partition in 1947, when the Muslim-majority portion of Bengal joined Pakistan while the Hindu-majority portion remained with India, that the medium became instrumental to the political discourse, according to Dulal Chandra Gain, a cartoonist who teaches at the Fine Art Institute at Dhaka. The fierce battles gave rise to cartoons that depicted the discrimination, death, and destruction wrought by the Pakistani generals. In 1971, during the Bangladesh War of Independence, political cartoons were key to the struggle to break away from Pakistan.

One political cartoon that remains iconic more than half a century later is a depiction of the then-president of Pakistan, Yahya Khan, who directed the massacre of Bengalis during the war. The cartoon, which was published in the weekly Joy Bangla on July 2, 1971, showed Khan with bulging red eyes, lips, and vampire-like teeth. “This brute has to be killed,” Khan is depicted to be saying.

Political cartoons remained popular in an independent Bangladesh, with newspapers often using them to express their stance on an issue; they often appeared on the front page or were dedicated an entire page. But today, the situation for political cartoonists has reached a critical stage — one that requires journalists and cartoonists to take a stand together.

But while the mainstream media has largely given up the fight, some smaller but influential dailies keep publishing political cartoons in defiance of the crackdown.

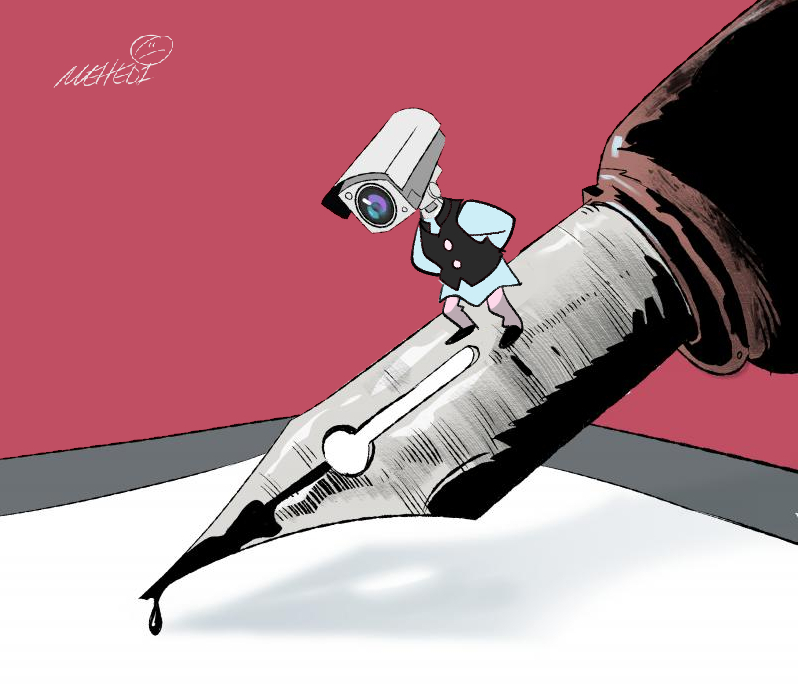

“I don’t want repressive laws to win over my passion,” said Mehedi Haque, a cartoonist who keeps drawing and publishing cartoons in independent papers. He is a regular contributor to the anti-establishment English-language daily New Age — despite the dismal pay and hate messages he says he receives. Haque has drawn Hasina cutting the national parliament like a cake as a commentary on her tight control over the legislature. He has also lampooned Tipu Munshi, the commerce minister. In one comic, Haque drew Munshi charting an inflation curve with lipstick because of comments he made saying that people weren’t struggling with high prices because "women were using lipstick three times a day, changing their sandals four times."

Haque believes if political cartoonists had stronger support from their news organizations, they would keep drawing. Instead, many are leaving the profession for more lucrative jobs such as drawing anime, a genre that is becoming more popular and doesn’t carry the threat of repression or prison time.

As Bangladesh becomes increasingly polarized, journalists’ associations are fractured when it comes to mobilizing against repressive legislation or advocating for journalists who try to fight back, according to Farida Yasmin, president of the National Press Club and a member of Parliament.

“We agreed on standing against the formulation of the DSA and we did,” Yasmin said, adding that the government had promised journalists the laws would never be used against them. But, in reality, many journalists have faced prosecution under the DSA, and because the journalism community is deeply divided along pro- and anti-government lines, it often fails to mobilize against new laws that can impede its work.

As for Kishore, after languishing in jail for ten months, he was eventually granted bail following a public outcry over the death of a fellow detainee, author Mushtaq Ahmed, who died while in custody facing similar charges. (Ahmed, who wrote a book titled “The Diary of a Crocodile Farmer,” was imprisoned for criticizing the government on social media and sharing Kishore’s cartoons.)

Left depressed and with disabiling injuries from the ordeal, Kishore now lives in Sweden, where he worked in a nursing home for awhile until he had to leave his job due to lasting fallout from the injuries he had suffered in custody.

But he says the ordeal hasn’t dimmed the passion for cartooning he first felt as a child, when his father would reward his good school grades with small gifts of MAD Magazine, The Adventures of Tintin, or Asterix comics, which sparked his lifelong love of telling powerful stories through cartooning.

“I will continue drawing cartoons,” he said, “to contribute to making the world a more humane place.”