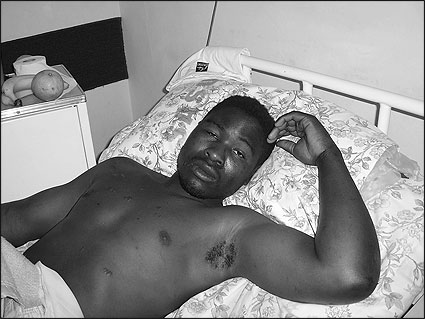

At three o’clock one morning, the head of Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organization in the town of Chipinge, accompanied by a gang of men, arrived at the home of Crispen Rambo, a car washer, and broke down his door. They beat him and hit him on the head with a piece of angle iron, then drove him in the official vehicle some 40 kilometers before beating him again and leaving him unconscious. Three hours later, after regaining consciousness, he was rescued by a stranger, who took him to the Movement for Democratic Change offices in Chipinge. He was admitted to S.A.S.U. Hospital in Mutare.

When Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe and his political party, the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front, lost the presidential and general elections in March for the first time in their 28-year history since liberating Rhodesia from colonial rule, Mugabe’s chief election officer, Emmerson Mnangagwa, blamed the media.

Mnangagwa singled out The Zimbabwean, the country’s mass circulation weekly independent newspaper, and SW Radio Africa, an independent broadcaster, for having adversely influenced the electorate. Within days our truck carrying 60,000 copies of the Africa Day (May 25) edition of The Zimbabwean on Sunday from South Africa to Zimbabwe was hijacked and torched by eight plain-clothed gunmen in unmarked vehicles brandishing new AK-47 assault rifles. Speaking at a government media event a few days later, Mugabe’s press secretary, George Charamba, declared that the government would “deal with” The Zimbabwean. He moved fast. By the beginning of June, a new “luxury” tariff had been officially announced, which slapped punitive duties on all foreign news publications.

Mugabe’s battle against the independent media hit a new low in 2003 with the passage of the misnamed Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA). This draconian legislation made it mandatory for all journalists and media organizations operating inside the country to be registered (and therefore policed) by the Media and Information Commission (MIC). Headed by an unashamed Mugabe apologist, Tafataona Mahoso, the MIC holds the dubious distinction of having closed down five independent newspapers including Zimbabwe’s first independent daily, The Daily News, and its sister Sunday, in its first two years of existence.

Exploiting a loophole in AIPPA, The Zimbabwean is published outside the country and trucked in from South Africa for sale on Thursdays. The entire content of the paper is available on The Zimbabwean Web site (www.thezimbabwean.co.uk) each Wednesday at midnight, with updates made several times each day during the rest of the week. A link to it is also sent via e-mail to online subscribers.

Since the beginning of June, The Zimbabwean has been subjected to exorbitant charges of 40 percent duty, plus 15 percent value-added tax, as well as a surcharge of 15 percent—all payable in foreign currency. Prior to this duty being imposed, the paper was charged in local dollars at the rate of 10 percent.

Because of this financial situation, we’ve been forced to suspend publication of the Sunday edition and cut severely our print run for the Thursday edition—from 200,000 to only 60,000 copies per week. Even at this limited level, we’ve had to pay more than $100,000 between early June and July 29 in duty costs to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority. In addition, the loss of our truck forced us to incur expenses of $40,000 in transport hire charges to get our newspapers into Zimbabwe.

Frantic project proposals to donors have elicited funding for another truck and 100 tons of newsprint, and checks poured in from well-wishers in response to British newspaper reports about the paper’s situation. But the cost is just too astronomical. While we have funds to enable us to keep going for another few weeks—after that, who knows?

Guerrilla Journalism

The Zimbabwean has grown quietly from 10,000 copies a week when it began in February 2005 to 200,000 copies in the run-up to the March elections—having become the largest newspaper ever to be published in Zimbabwe. It effectively penetrated Mugabe’s media blackout and gave accurate information and hope to millions of Zimbabweans suffering at home under Mugabe’s rule. Active market penetration into the rural areas provided information, as opposed to crude propaganda, to the people who had hitherto formed Mugabe’s main stronghold. At the same time, our Web site grew phenomenally—peaking at 3.8 million hits a week during the election period. The paper edition is also available in 52 countries through newspaperdirect.com.

Because of the AIPPA legislation, it is not possible for our reporters—who are not officially accredited—to operate as journalists within the Zimbabwean system. This means that they cannot attend or cover official events, nor can they seek official comment from police or army spokesmen. Simply by being in the country—and doing any reporting about what’s happening there—means they are constantly at risk of being arrested, beaten or worse.

In the past few years countless numbers of journalists have been harassed, arrested, beaten, tortured and locked up. Among them was Gift Phiri, chief reporter for The Zimbabwean, who was tortured and had his finger broken by Mugabe’s extra-legal militia forces (dressed in police uniforms) last year. Cameraman Edward Chikomba has been killed. In no case of physical torture, harassment or murder of a journalist has there been a conviction.

Under such conditions it is virtually impossible to operate as a professional news organization. We do our best to get the story out and break the silence by exposing the appalling human rights abuses and government corruption. The finer points of journalism have, regrettably, had to be compromised in the desperate battle for access to information. This is guerrilla journalism and, as in guerrilla war, shiny boots and smart parade-ground salutes have to be sacrificed to get the battle won.

How We Report

We gather our news from a variety of sources. Zimbabweans love to tell stories. There is no shortage of well informed, thinking people to offer opinion pieces and analysis. We have countless contributors—all unpaid. In addition, through the years there have been numerous “leaks” from disgruntled intelligence and military officers. It might surprise some to learn that many government officials at all levels have been keen to provide us with information. On some occasions, even cabinet ministers are eager to be our Deep Throat.

In such situations, there is only one way we can protect our sources from horrific consequences: We must give them total anonymity. And so we have. The same applies to members of various opposition political parties operating in Zimbabwe, among whom we can always find people with good information to pass along. The challenge for us is that human nature being what it is, the temptation to embellish information is always present. So we need to corroborate and check what we are told, and so we do this to the best of our ability while protecting the identity of those who gave us the information. There is always the niggling doubt that the information could be planted—and that our newspaper could be used to further someone’s agenda. In fact, there have been a number of instances when we’ve spotted government intelligence attempts to destroy our credibility. This is a constant worry.

If, after publication, somebody approaches us with an alternative viewpoint or new and different information that presents the “other side” to a story we published, we provide them with equal opportunity to make their point.

Modern technology has been a helpful partner in enabling us to publish news about Zimbabwe while being thousands of miles away. (Those of us directing publication of The Zimbabwean face the threat of death at the hands of Mugabe’s forces if we return to Zimbabwe.) Digital media allow citizens within Zimbabwe to report news and send the information and photographs to us. The Zimbabwean receives more than its fair share of its news in this way; today, reports received from nonjournalists in Zimbabwe is perhaps the main source of the information contained in our columns.

However, communicating with our reporters (and citizen reporters) on the ground inside Zimbabwe is a huge challenge. Apart from the constant electricity blackouts, bandwidth is limited, and e-mails are monitored by government officials. We work on the premise that our e-mails are intercepted and telephone calls bugged. All of this does not make for clear communication. Those who provide information to us also have to avoid public places and Internet cafés where Central Intelligence Organization operatives and informers always hang around. At great cost, we’ve provided laptop computers and various means of communication to our staff reporters so they don’t need to rely on these public locations.

We are fully aware that those who report for The Zimbabwean are constantly at risk. They are under strict instructions not to meet new sources in isolated spots, not to take information or informants at face value, and to always make sure that someone else knows exactly where they are. At the newspaper, we receive lots of threats, and we do not take them lightly. Mugabe’s militia, as well as state security agents, are more than capable and willing to thrash, torture and even to kill journalists. We rely constantly on the guidance and assistance of Lawyers for Human Rights, who are always ready to rush to court on our behalf, as they’ve had to do on several occasions.

In mid-July another “official” death list surfaced and made the rounds of Zimbabwean Internet sites. There was a chilling new dimension to this one. After listing pretty much every known living Zimbabwean journalist not working for the state-controlled media, the final paragraph says, “The majority of those named on the list, although they are living in the bliss and security of the Diaspora and the anonymity of cyberspace, their family members will not be so lucky.”

Despite the family being sacrosanct in Zimbabwean culture for centuries—and never before threatened—Mugabe has taken horror to new heights. This action flies in the face of everything decent, as what was once unthinkable has become reality. My fellow journalists and I have chosen to fight Mugabe to the death. We are prepared to face the repercussions of our actions. Some have already paid the ultimate sacrifice. But can we put our families at risk? That is a tough one.

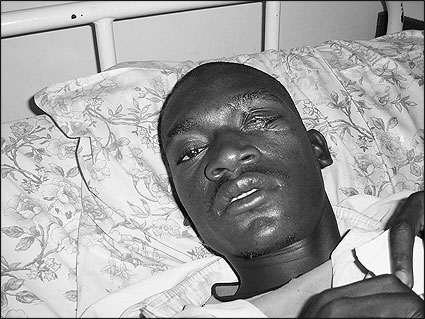

While celebrating the victory of Mathias Mlambo in the Musirizwi area of Chipinge, Daniel Simango, 24, was attacked and beaten by four ZANU-PF youths (members of Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front party), one of whom stabbed him in the eye. He ran into hiding, then came to the Movement for Democratic Change offices in Chipinge, and from there he was brought to the S.A.S.U. Hospital.

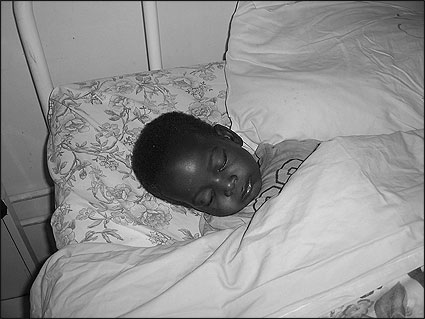

The Meikle farmhouse in Zimbabwe, where 19-month-old Jesse Sazukwa lived, was burned by the farm’s owner and a young man from ZANU–PF, according to a report given by her mother. Because of the fire, Jesse received medical attention, which likely saved her life because her doctors treated her malaria as well.

Wilf Mbanga is the editor of The Zimbabwean.