Journalists are truth-tellers. But I think most of us have been lying to ourselves. Our profession is crumbling and we blame the Web for killing our business model. Yet it’s not the business model that changed on us. It’s the culture.

Mainstream media were doing fine when information was hard to get and even harder to distribute. The public expected journalists to report the important stories, pull together information from sports scores to stock market results, and then deliver it all to our doorsteps, radios and TVs. People trusted journalists and, on our side, we delivered news that was relevant—it helped people connect with neighbors, be active citizens, and lead richer lives.

Advertisers, of course, footed the bill for newsgathering. They wanted exposure and paid because people, lots of people, were reading our newspapers or listening to and watching our news programs.

But things started to change well before the Web became popular. Over the past few decades, news conglomerates took over local papers and stations. Then they cut on-the-ground reporters, included more syndicated content from news services, and focused local coverage on storms, fires, crashes and crime to pad profit margins. The news became less local and less relevant, and reporters became less connected to their communities. Surveys show a steep drop in public trust in journalism occurring during the past 25 years.

As discontent grew among the audience, the Internet arrived. Now people had choices. If the local paper and stations weren’t considered trustworthy and journalists seemed detached from what really mattered to them, people could find what they wanted elsewhere. What’s more, they could stop being passive recipients. They could dig deeply into topics, follow their interests, and share their knowledge and passions with others who cared about similar things.

Connecting Through Trust

The truth is the Internet didn’t steal the audience. We lost it. Today fewer people are systematically reading our papers and tuning into our news programs for a simple reason—many people don’t feel we serve them anymore. We are, literally, out of touch.

Today, people expect to share information, not be fed it. They expect to be listened to when they have knowledge and raise questions. They want news that connects with their lives and interests. They want control over their information. And they want connection—they give their trust to those they engage with—people who talk with them, listen and maintain a relationship.

Trust is key. Many younger people don’t look for news anymore because it comes to them. They simply assume their network of friends—those they trust—will tell them when something interesting or important happens and send them whatever their friends deem to be trustworthy sources, from articles, blogs, podcasts, Twitter feeds, or videos.

Mainstream media are low on the trust scale for many and have been slow to reach out in a genuine way to engage people. Many news organizations think interaction is giving people buttons to push on Web sites or creating a walled space where people can “comment” on the news or post their own “iReports.”

People aren’t fooled by false interaction if they see that news staff don’t read the comments or citizen reports, respond and pursue the best ideas and knowledge of the audience to improve their own reporting. Journalists can’t make reporting more relevant to the public until we stop assuming that we know what people want and start listening to the audience.

We can’t create relevance through limited readership studies and polls, or simply by adding neighborhood sections to our Web sites. We need to listen, ask questions, and be genuinely open to what our readers, listeners and watchers tell us is important everyday. We need to create a new journalism of partnership, rather than preaching.

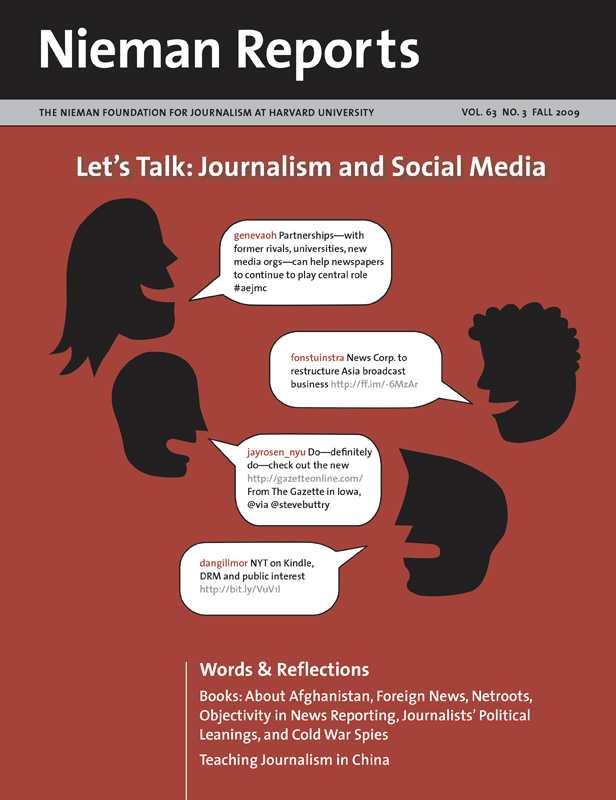

And that’s where social media can guide us. If we pay attention and use these tools, we can better understand today’s culture and what creates value for people.

Relying on Collective Wisdom

Today’s new culture is about connection and relationship. Social networks are humming because they fit the spirit of the time, not because they created the spirit of sharing. They’re about listening to others and responding. They’re about pursuing our interests because we know they will converge with the interests of others. The new culture values sharing information and being surprised by the experiences, knowledge and voices of others.

The old journalism, with its overreliance on the same experts and analysts, is out of touch with a culture of information sharing, connection and the collective wisdom of diverse voices passing along direct experience.

Take Wikipedia as an example. For better or worse, most school kids treat it as the first place to go for information, and so do many adults. It’s not written by scholars, as is Encyclopædia Britannica, but by citizen experts. In today’s culture, collective expertise carries as much or more weight than scholarship or deference to titles. And while fewer than 45,000 people are actively contributing to the nearly three million English articles on the site, people know that anyone can contribute, and they have trust in the culture’s collective wisdom.

Digg and reddit are popular as sites because they are about collective wisdom and trust. These social bookmarking sites help people find relevant news based on who is recommending stories. Anyone can play, even if experienced and dedicated users have an advantage. Twitter is half diary and half stream of consciousness, and it is all about relationships and trust because it is easy to follow people, see if there is a connection, and drop those you don’t like.

Changing Journalism’s Culture

Social media sites are not doing journalism, though sometimes breaking news shows up there (like when a plane crash-lands in the Hudson River). For the most part, they rely on news coverage from mainstream media organizations to produce their value. And these sites are not yet profitable. They are not models for the new journalism. But they do serve the new culture and point to how news organizations must change to be considered relevant and value-creating.

Of course, news organizations are rushing onto social networks, adding social bookmark buttons, and creating Twitter feeds at a torrid pace. But for the wrong reasons. You can hear the cries in newsrooms of “we need to be on Facebook, we need to Twitter” as a fervent attempt to win followers and increase traffic on their sites.

Mainstream media see social media as tools to help them distribute and market their content. Only the savviest of journalists are using the networks for the real value they provide in today’s culture—as ways to establish relationships and listen to others. The bright news organizations and journalists spend as much time listening on Twitter as they do tweeting.

Most of the discussion about the “future of journalism” these days centers on finding the new business model that will support journalism in the Internet age. Yet that is premature. There is no magic model that will save us, if only we could find it. We have no business model unless people need our work to enrich their daily lives and value it highly enough to depend on it.

Unquestionably, we must be creative about designing new models and smart about marketing our work. But a fact of business is that people only pay for what has obvious value to them. Every good business plan starts by explaining how it creates value for the customer.

The problem with mainstream media isn’t that we’ve lost our business model. We’ve lost our value. We are not as important to the lives of our audience as we once were. Social media are the route back to a connection with the audience. And if we use them to listen, we’ll learn how we can add value in the new culture.

The new journalism must be a journalism of partnership. Only with trust and connection will a new business model emerge.

Michael Skoler, a 1993 Nieman Fellow, is a Reynolds Journalism Institute Fellow at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. He founded the Public Insight Journalism model used by a dozen public broadcasting newsrooms to partner with their audiences. He wrote “Fear, Loathing and the Promise of Public Insight Journalism” in the Winter 2005 Nieman Reports.