When a gunman killed 51 people and injured dozens more at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March, the official response was swift. Restrictions were imposed on military-style semiautomatic weapons and assault rifles, and on magazines and ammunition. The ban was made permanent by an all-but-unanimous vote in Parliament, followed by a $136 million allocation to buy back semiautomatic firearms by December. And the prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, wore a hijab to console families of victims and other Muslims.

But it was another gesture that most caught the attention of a group of American activists and policymakers: Ardern proclaimed that she would never name the shooter, and a judge ordered that photos of his face, when he appeared in court, be blurred “to preserve any fair trial rights.” They were, though some journalism outlets that complied with the order also published or posted images of the suspect in which his face was visible. When the accused returned to be formally charged with murder and terrorism—his trial will begin next year—some of New Zealand’s major media organizations vowed “to the extent that is compatible with the principles of open justice, [to] limit any coverage of statements that actively champion white supremacist or terrorist ideology.”

It was the highest-profile validation of an idea that has come to be known as “strategic silence,” pushed by relatives of victims, law enforcement agencies, criminologists, academic researchers—and a growing number of readers, listeners, and viewers—to downplay the names, images, and ideologies of perpetrators of mass crime. It was also an example of how media organizations are struggling with this strategy.

It’s not clear where the expression “strategic silence” originated as it pertains to journalism (it’s long been a term of art in crisis public relations). danah boyd and Joan Donovan, former colleagues at the research institute Data & Society, are largely credited with using it most prominently last year in a story in The Guardian about efforts through history to “quarantine” the Ku Klux Klan, but the two activists say it didn’t actually start with them. Among the earliest instances in which journalists used those words were in the mid-1990s to describe not something they were doing, but that the Clinton administration was, stonewalling the media in the midst of Whitewater and other scandals. But the concept itself has been around for almost a century. It was known as “dignified silence” in the 1920s, when the black press used it to downplay news about the Ku Klux Klan, and “quarantining” when Jewish organizations pushed journalists to give less attention to the ideas of white supremacists and American Nazis.

Ardern’s avowal to not name the mass shooter was the highest-profile validation of an idea that has come to be known as “strategic silence”

Whatever it’s called, it’s gaining traction. A study of 6,337 stories about the Christchurch attacks found that only 14 percent of U.S. publications named the shooter and almost none linked to his manifesto or the forum where he posted it. A handful of prominent journalists have said they’ve made a policy of this, including CNN’s Anderson Cooper. Media watchers say there’s anecdotal evidence that news outlets no longer splash the names and faces of mass shooters on screens and pages as much as they once did.

There’s another thrust of the strategic silence movement: to stop journalists from sharing not only shooters’ manifestos, but incendiary political and cultural speech, and to debunk it, even when it’s coming from the White House. This has gotten much more limited momentum; a review by the progressive research organization Media Matters for America suggests that, in the case of untrue tweets by President Donald Trump, for instance, media outlets continue to more often amplify than filter or rebut them.

Political journalist Michael Barbaro, host of The New York Times podcast “The Daily,” said it would be selective about reporting Trump’s remarks on immigration before last year’s midterm elections. “‘The Daily’ is deliberately playing down these events because they are clearly not policy remarks or policy announcements,” Barbaro tweeted. “They are deliberate attempts to inflame the electorate before the midterms.” And MSNBC opted to not air a speech by Trump around the same time about the caravan of Central American migrants Trump called an invasion. “In an abundance of caution, we’ve decided to monitor those remarks, fact-check them … and then bring you the important news from them,” the anchor said.

Proponents of strategic silence applaud depriving mass killers of the fame that some research has concluded helps motivate their crimes. They also applaud media that decline to publish or broadcast extremist credos or false claims, stopping the propaganda from finding wider audiences they say their promoters have become adept at manipulating journalists into supplying.

Journalists including Washington Postmedia critic Erik Wemple respond that this is a path as dangerous as it might be well intentioned. Deciding that it’s not appropriate to post, publish, or broadcast an untrue tweet from a person of national importance, or information about someone who shoots people in a school or church, “starts to run into the public’s right to know,” says Wemple, “and that is in the extent to which it suppresses legitimate journalistic inquiry.”

For his part, filmmaker Errol Morris, who couldn’t get U.S. distribution for his 2018 documentary about Steve Bannon, “American Dharma,” isn’t sure that hearing contrary points of view helps people better understand and therefore outmaneuver them—that “feel-good ideas will win out over bad ideas.” But he bristles at a strategy of blocking or—as it’s also started to be called—“de-platforming” them. “I don’t think the ostrich approach here is recommended—that I’ll just stick my head in the ground and hope the danger passes.”

It’s a fraught and complex debate now being played out in more and more newsrooms with what some critics say are the highest possible stakes. Since political strategic silence ebbs and flows with the election cycle, it’s likely to present itself again as 2020 nears. To boyd—Data & Society’s founder and president, who styles her name in all lowercase letters—the question isn’t whether or not the public should know, “but at what point are you reporting on something that’s happening and at what point are you aiding and abetting the conspiracy?”

There does seem to be consensus about one thing: That this is, as Morris puts it, “an expression of enormous frustration that people feel—I might say including myself—that politics has gotten out of hand. That it’s not just about right and left; it’s about reason and unreason.”

Trouble is, he says, “if you curtail free speech, who gets to decide? Who gets vested with the authority to say?”

Proponents of strategic silence applaud depriving mass killers of the fame that some research has concluded helps motivate their crimes

Strategic silence isn’t necessarily encouraging journalists to censor themselves, says Whitney Phillips, an assistant professor of communications at Syracuse University and an expert on online trolling who has studied how the media help amplify the ideology of the alt-right. “I understand the kneejerk response of, ‘Somebody is telling me not to do my job any more,’” she says. “That isn’t it.”

The focus needs to be on the “strategic” and not the “silent” part of the term, says Phillips, author of “The Oxygen of Amplification,” a report about this topic.

“There are ways to communicate stories without playing into a manipulator’s game,” she says: by focusing not just on the speaker or the speech, but on the people affected by it. When journalists report about conspiracy theories, political misinformation, and racist or misogynistic messages, says Phillips, “what’s missing from that account in almost every case is the perspective of the people who are being targeted by that offensive speech. It’s almost always all about the speech and not about the victims.”

The controversial November 2017 New York Timesstory “A Voice of Hate in America’s Heartland,” about the far-right Midwesterner popularly remembered as “the Nazi next door,” for instance, left out the perspective of neighbors who might have been the targets of his animosity, she says. “It didn’t consider what that framing is like for them. That’s not balanced reporting.”

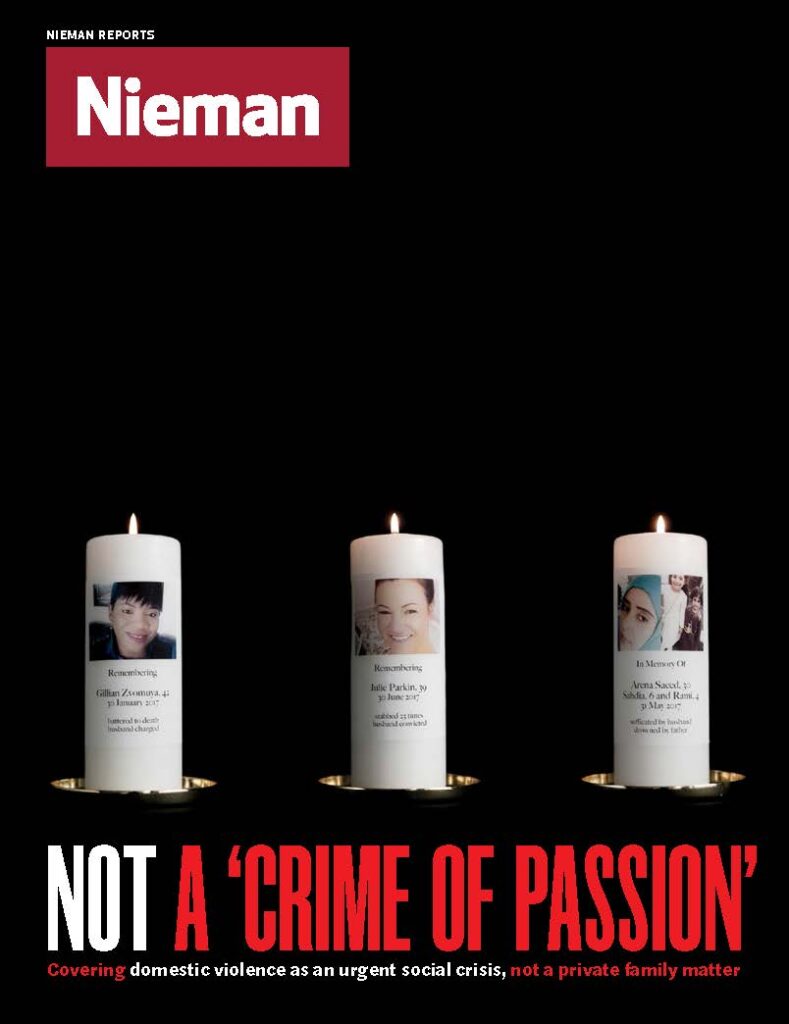

Phillips returns to the example that has so far dominated most discussion of strategic silence: the person who commits a mass crime. “Why does the camera have to automatically be pointed in the shooter’s face? You can engage with the stories with a shift of the camera, and suddenly you’re talking about people other than the shooter,” such as victims and responders.

News organizations practice on a daily basis even more complete strategic silence than that, she says. Among other ways, that happens when they decide to withhold information about suicides for exactly the same reasons some people are advocating for strategic silence in the reporting of hate speech or mass crimes: to avoid encouraging copycats.

They’ve also held back information about journalists abducted abroad. The New York Times led a media blackout about the kidnapping of its correspondent David Rohde, along with two Afghan colleagues, in Afghanistan by the Taliban until he managed to escape. Several major media outlets knew about a prisoner exchange to win the release of Jason Rezaian, Tehran bureau chief of The Washington Post, but didn’t report it. NBC kept secret the abduction in Syria of correspondent Richard Engel and his crew until they were freed.

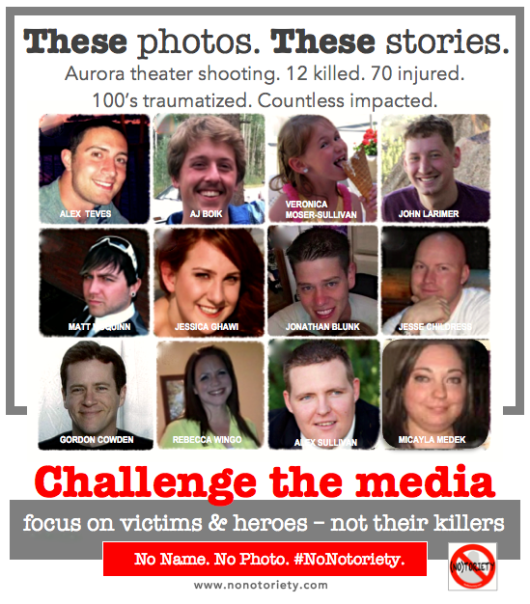

“Why will you do it for your own but you won’t do it for my child?” asks Tom Teves, whose, son, Alex, was among the 12 people killed in the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shootings in 2012 when he stood up to pull his girlfriend to safety. Yet after Aurora, Teves said, “All the media showed was the killer, the killer. None of it was about the victims.”

Teves has established No Notoriety, one of two principal organizations that have been pushing to starve mass shooters of media attention. The other is Don’t Name Them, coordinated by the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center (ALERRT) at Texas State University.

Neither advocates for suspects’ names to be withheld altogether; No Notoriety says the facts about their backgrounds and motivations should be reported, but that journalists should resist “adding complementary color to the individual or their actions, and downplay the individual’s name and likeness” unless he’s still at large. Manifestos should never be shared, it says, while names and likenesses of people killed and injured should be elevated “to send the message their lives are more important than the killer’s actions.”

Don’t Name Them counsels law enforcement officers to not sensationalize the names of shooters in media briefings, recognize media outlets that downplay the names, circulate petitions encouraging journalists to shift the focus to victims and people who intervene, and provide letters readers, listeners, and viewers can send to media outlets. Once the killers are captured, it says, the killer’s name is “no longer a part of the story.”

That there are life-and-death repercussions to what journalists decide to include and exclude from their coverage is backed up by a 2015 study led by Sherry Towers, a research professor at Arizona State University who uses mathematical and computational modeling to study such things as the spread of disease and behaviors. It found “significant evidence” that high-profile mass killings using firearms provoke copycat incidents soon afterward in what Towers has called “a contagion effect.” More recent research, led by University of Alabama criminologist Adam Lankford, did not find that short-term contagion had occurred, but that there may have been some imitators motivated over the longer term.

Something similar happens when radical and racist ideologies are shared. This, at least, is not a new phenomenon; when the New York Worldran an investigation of the Ku Klux Klan in 1921 that included an image of a secret membership application, according to historian Felix Harcourt of Austin College, thousands of readers ripped it out and joined. The American Nazi Party recruited more members in areas where local newspapers covered its resurgence in the 1960s than in places where Jewish community groups persuaded them not to, say boyd and Donovan, who is now director of the Technology and Social Change Research Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.

But the advent of social media has accelerated the phenomenon. As soon as journalists started to report about how Pepe the Frog had become a symbol of white supremacists, searches for and shares of it only propelled it into the mainstream.

Repeating Alex Jones’s assertion that the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut was faked helped it spread, boyd says.

And when a 25-year-old Canadian rammed a van into pedestrians in Toronto, killing 10 and injuring 16, news coverage widely included the fact that he subscribed to an obscure misogynistic subculture of men who consider themselves involuntarily celibate; online searches for it spiked, Google Trends data show, increasing 20-fold in one day, and staying higher than before the attack.

Instead of giving audiences road maps to these kinds of things, advises boyd, journalists should “talk about toxic forms of masculinity. Talk about hate-fueled attitudes that lead to terrorism. Just don’t amplify the phrases and logics that hate-mongers are seeking to amplify.”

Reporters say they can’t ignore, for instance, the perversity of people who believe that Sandy Hook was staged. Critics argue this perpetuates such theories, or sends audiences off to seek out further information elsewhere. “Yes, there’s a reason to say that is occurring, but there’s no reason to name Alex Jones or InfoWars and make the story about him,” says boyd, who prefers the term “strategic amplification” to “strategic silence.”

In one case, two news organizations confronted this in different ways.

The first, NPR, last year broadcast an interview with Jason Kessler, who organized the Charlottesville rally and was organizing a follow-up in D.C., in which Kessler said, among other things, that “as a matter of science,” blacks were the least intelligent among racial groups. In the resulting uproar, listeners reminded the network of that time when the New York World was turned into an involuntary recruiting tool for the KKK, says Elizabeth Jensen, the network’s public editor. “They were saying, ‘You’re no different,’” Jensen says. She writes in a column about the interview that the network was not necessarily wrong to run the interview, but NPR was wrong to not use facts to challenge Kessler’s ranking of intelligence by race; he cited the work of controversial scholar Charles Murray, and the host responded only, “Charles Murray? Really?” NPR did not air the portion of the hourlong interview (it was reduced to seven minutes) in which Kessler was asked about the death in Charlottesville of counterprotester Heather Heyer.

The second, HBO’s “Vice News Tonight,” also covered the white nationalist protesters who had descended on Charlottesville. Yet while it, too, got some criticism for providing them with exposure, there was positive feedback for the way that the reporting by correspondent Elle Reeve contradicted assertions by Trump (“I think there is blame on both sides”) by showing persuasively that the white nationalists had been driven less by ideology than by a determination to cause violence. One of the white supremacists on whom she focused, Christopher Cantwell, was subsequently charged with and pleaded guilty to two counts of misdemeanor assault and battery for pepper-spraying people at the rally; his Facebook and Instagram profiles were shut down because of statements he made about it, and he said Venmo and PayPal disabled his accounts.

There’s pressure, too, for journalists to do a better job of calling out the growing number of instances in which Trump and others misstate facts. In their own tweets, they repeat the president’s misinformation 65 percent of the time without rebutting it, a Media Matters study found, or 19 times per day. Matt Gertz, a Media Matters senior fellow who coauthored the analysis, calls this “privileging the lie.”

He cites a good and a bad way to handle this. The bad: A “Face the Nation”tweet that said, unquestioningly, “The chant now should be ‘finish the wall,’ as opposed to ‘build the wall,’ because we’re building a lot of wall,” @realDonaldTrump said today.” The good, from The Washington Post: “Trump claims a wall is needed to stop human trafficking. No data back up his claim.”

Related Reading

Covering White Supremacy and White Nationalism

By Dana Coester

These days, Gertz says, some longstanding journalistic practices should fall into question, “and one is that what the president says is inherently newsworthy.” If it is, and it’s true, he says, “by all means tell the public about it. If it’s not true, do the work of pointing that out rather than amplifying information that isn’t accurate.”

It’s those shootings that most directly suggest the copycat effect. There’s an abundance of evidence that the killers study and are inspired by the actions and messages of earlier offenders, such as the spreadsheets of incidents with perpetrators’ names and body counts that was kept by the 20-year-old who fatally shot 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook. These also lay bare how many are motivated by a desire for fame. “When you see me on the news, you’ll know who I am,” said the 19-year-old who allegedly killed 17 people and wounded another 17 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

The strategic silence movement, as it applies to tragedies like these, is “not suggesting hiding people from the public. We’re just saying that the focus needs to be switched,” says J. Pete Blair, a criminologist and ALERRT’s director. “Crime Prevention 101 says there are certain things we know can reduce crime, and one of those things is if we reduce the rewards for the crime.”

This idea is finding widespread acceptance from law enforcement officials on whom journalists depend for information. The International Association of Chiefs of Police, in a resolution, urged what it called “responsible media coverage for the sake of public safety,” meaning that journalists should restrict their reporting of the names and photos of alleged assailants unless they are at large. The Major Cities Chiefs Association has adopted a similar policy.

The ways journalists and activists push strategic silence differ

These decrees have started spilling over into practice. After a 26-year-old Air Force veteran killed a couple dozen congregants and wounded 20 others at a Baptist church in Sutherland Springs, Texas in 2017, authorities stopped saying his name. The sheriff overseeing the response to the 2015 Oregon community college shooting, John Hanlin, also would not name the shooter publicly. Police investigating a shooting in Virginia Beach that killed 12 people in a municipal office building in May said they would name the shooter only once.

In none of those cases were the names withheld from official documents, and most media organizations used them. But some of the pressure has been more strident, suggesting that journalists may be morally complicit if they do not follow edicts on withholding the names of shooters.

The Washington Post’sWemple decries external pressure like this. These decisions should be confined to newsrooms, he says: “It’s not the role of a sheriff or the attorney general or the town police chief to tell the news media how to roll. If they want to say, ‘This is what we’re doing and we think it’s a good idea,’ that’s in their purview. We in the media will do what we feel is newsworthy and ethical.”

But other journalists have said that they agree with the idea of lessening attention given to the killers. The most prominent: CNN’s Cooper, who Teves challenged on the air just days after his son was killed. Cooper’s colleague, Chris Cuomo, also noted that, in his coverage of the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting, he never used the shooter’s name, and Megyn Kelly, who was then on Fox News, tweeted after the shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon:“TV gives infamy he prob[ably] desired. Don’t!”

Kyle Clark, an anchor at 9News in Denver who was on the air for 17 consecutive hours on the day of the Aurora shootings, has also chosen—with his station’s support—to downplay the identities of shooters. There’s no formal protocol, Clark says; it’s a case-by-case decision, and a matter of the names becoming of declining importance as investigations mature.

“On the first day their names matter a lot,” says Clark, recounting how this worked in the wake of a shooting in the Denver suburb of Highlands Ranch in May that killed one and injured eight; the suspects are an 18-year-old and a juvenile. “And the first time that the adult suspect appears in court, I believe that images of that person matter a lot. It’s very important, especially on the local news level that people hear the name and see the face so they can come forward with information, if they have any.”

After that, however, Clark begins to pull back on naming suspects. A story may identify an alleged offender once, but then refer to him as “the suspected shooter.” “When we are seeing research and evidence on top of anecdote that contagion is real and that people are seeking notoriety, journalists have a responsibility to minimize harm while balancing that with the public’s need to know and the public’s right to know,” Clark says.

Local journalists may be more receptive to this than national reporters who parachute into crime scenes, Clark says, since they see more immediate evidence of how naming perpetrators affects victims and survivors.

Many other media have landed in a middle ground. NPR standards and practices editor Mark Memmott, for example, has advised in internal memos that “the name of the shooter does NOT have to be endlessly repeated.” As an example of this, he drew attention to a “Morning Edition” segment about the Las Vegas attack about, among other things, how the gunman had modified his rifles. But it never used his name, which wasn’t pertinent to the policy question over continuing to allow the legal sale of bump fire stocks that can turn a rifle into a semiautomatic weapon. “I don’t think anything was lost because of that,” wrote Memmott.

Including listener interest, according to other research conducted by scholars at Northeastern and West Chester universities. It shows that readers, listeners, and viewers don’t need the intimate details of perpetrators’ lives to be drawn to stories about mass crimes. Seventy-three percent read a story beyond the first paragraph that focused on a person who stopped a shooting at a school, compared to 56 percent who chose to read past the first paragraph of a story that focused on the killer. Fifty-two percent read past the first paragraph of a story about a victim. Media outlets that provide excessive coverage of the perpetrators of such attacks “may not be giving consumers what they want,” the researchers concluded.

There’s pushback against the various kinds of strategic silence, too.

CNN’s Don Lemon said of the Oregon shooter, “We must identify him, because that is our job.” The people lobbying against this “could do more harm than good,” USA Todayeditorialized, “if they give public officials an excuse to withhold information, impede investigative reporting on what makes killers tick, or provide the gun lobby with a way to point fingers at the news media in an effort to deflect pressure for common-sense laws.”

Journalists and others who pay attention to strategic silence say they’ve started to see coverage slowly change

Rather than diminish the Sandy Hook shooter, the Hartford Courantspent five years in a legal battle that went all the way to the state Supreme Court to get access to his journals. That was meant to give not only a clearer picture of the motivations behind that crime, but the red flags that could prevent more like it, publisher and editor-in-chief Andrew Julien says.

But the newspaper was mindful of the issues raised by the strategic silence movement when it presented the resulting coverage, Julien says. (The documents were also part of a collaboration between the Courant and “Frontline.”) The shooter’s name was in the headline, but the lead image was not of him; it was of the sign outside of Sandy Hook Elementary, draped with balloons. Nor was there a photo of the gunman on the Facebook page or in the thumbnail on the homepage of the Courant’s website. And that spreadsheet of the earlier mass killers that he kept? It was reported about, but not among the documents the newspaper republished.

For Clark, too, there are limits. He says journalists shouldn’t set hard-and-fast rules for themselves or take pledges to do things one way or another, as No Notoriety proposes. And he’s cautious about extending the same principles into coverage of hate speech or conspiracy assertions, especially from political figures. “When you’re talking about a public figure, there’s a duty for journalists to show and report what they say, no matter how outrageous,” says Clark.

That’s an example of how journalists and activists who push strategic silence differ. When someone says something odious or untrue, repeat it, but debunk it, says Mike Jempson, director of the MediaWise Trust, a British nonprofit that provides training in ethics for media professionals and studies the impact of their work.

Journalists’ responsibility is not to filter what they tell the public, but “to provide some sort of context,” Jempson says. “And if people are saying things which are evidently wrong or false, it’s our job to challenge that. So saying all Mexicans are rapists or whatever nonsense Trump has been saying, I think we need to know that this person has these views and that they’re factually inaccurate.”

That thinking holds that media-savvy readers, listeners, and viewers can see this for themselves, or can interpret—if they can only read them—how repugnant are the messages of extremists. “It’s upsetting to hear blatant lies and racism and hate speech. But if you believe that humans have rationality, put it out there in the marketplace of ideas, along with the truth,” says Paul Levinson, a longtime journalist and now a professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University.

Assuming media literacy in the fast-moving blur of the digital landscape, however, may be optimistic, says Aimee Rinehart, partnerships and development director at First Draft, which uses technology to decide which purposefully misleading messages to address and correct—and which to ignore—based on the likelihood that they’ll be spread.

Journalists’ assumption is that “you throw facts at someone and that’s going to change their minds,” says Phillips. “That’s not how people make their minds up.” Pre-existing bias, personal characteristics and experiences, and other factors have much to do with it; a study in December by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business found that people make judgments and decisions based on comparatively little new information.

Consider the flip side, says Mark Follman, national affairs editor at Mother Jones: If the media doesn’t initially confront an issue such as white supremacists and what their motivation is, or who it was that opened fire on a crowd, “then you have bad actors on social media putting up false information—using the opportunity of an attack to say, ‘Look, it was a Muslim who was shooting up this school.’” That’s what happened in the case of the Umpqua Community College shooting, after which right-wing websites variously called the 26-year-old student who killed nine and injured eight a Muslim, an Islamist, or an ISIS sympathizer. He was a student who described himself as nonreligious and a Republican.

The debate rages on, but journalists and others who pay attention to strategic silence say they’ve started to see coverage slowly change.

“Certainly after Charlottesville, that’s where the receptivity shifted,” Phillips says. “And then the Christchurch shootings, that has been an even more marked point of shift, where folks are increasingly aware of amplification chains. There’s no easy solution. People are more willing to do it better and concerned about the importance of doing it better.”

Follman says he thinks a better way to describe the new approach of many journalists is “strategic diminishment. I don’t think it’s silence.” For example, he says, “In my view it’s much more about proportionality and balance. When big attacks happen now there tends to be less of a front-and-center spotlight on the perpetrators, on focusing and reporting on them in ways that makes them almost exclusively the story.”

During the South Florida Sun-Sentinel’s Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of the Parkland shootings, the newspaper’s reporters—under pressure from advocacy groups and some readers—started leaving the suspect’s name out of stories, says Dana Banker, managing editor.

She made them put it back, within reason.

Even where journalists stand firm about the public’s right to know, they say the strategic silence movement has them thinking

“We told the staff, ‘You’ve got to stick to your basic standards here,’” says Banker. She defines these as, “Our obligation first and foremost is to our readers and to get the information out there.”

In Parkland, too, digging deep into the alleged shooter’s history and motivations had important policy implications, since authorities had missed or failed to respond to signs he was a threat. “What happened with this kid and his experience in the school system is important. It’s important to know,” says Banker.

That’s been true not only in Parkland. It was after the publication of the manifesto of the man known as the Unabomber that his brother recognized the writing, helping catch him. Coverage of the perpetrators of the shootings at Virginia Tech, the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas exposed shortcomings in mental health and criminal record-keeping and reporting and loopholes in gun laws.

The Sutherland Springs shooter, for example, should not have been allowed to buy or possess firearms or ammunition, since he had been convicted of domestic violence in a court-martial while in the Air Force. But the Air Force failed to submit the conviction to the FBI database that’s used for gun checks. When this fact was unearthed by journalists investigating him, the Air Force promised a review.

But even where journalists stand firm about the public’s right to know, they say the strategic silence movement has them thinking.

In the early stages of the Parkland shooting, “we probably played the guy’s picture a little bigger than we should have on certain occasions,” Banker says of the teenager who allegedly carried it out. “Certainly the outreach and the complaints made us more aware of the issue. We did get more sensitive about not throwing his name into headlines. I do think our sensitivity certainly grew after the initial weeks.”

She’ll have more opportunities to test this; the Parkland suspect’s trial is tentatively scheduled for January.

So will the Courant’sJulien. That’s because the lawsuit brought by six Sandy Hook families against Alex Jones is also slowly moving through the courts.

“We don’t go into great detail about all the conspiracy theories, because if you read some of this stuff, there’s some really dark things being said about the kids and their families,” Julien says. “But in a court proceeding that balances issues of what is inappropriate and what is free speech, we don’t think we can ignore it just because some people might Google Alex Jones.”

He, too, says there’s much more conversation in his newsroom now, and among editors around the country, about how to cover lies, mass crimes, conspiracy theories, and the ideologies that drive them. “What we’re really talking about,” Julien says, “is what’s the right balance between not aggrandizing these things and also fulfilling our fundamental obligation to inform the public about what’s going on.”