Reporters pursued the president in a feeding frenzy. White House resistance didn’t deter them from pounding away, day after day, at his credibility.

Critics, however, believed the issue to be hyped out of proportion. To them, parts of the media had abandoned their traditional neutrality for a misguided moral crusade to uphold the rule of law.

“The gulf between what these critics are saying and what the press is doing,” a Washington Post columnist observed, “reflects among other things confusion about our role in American life.”

That assessment was not about President Joe Biden or former President Donald Trump during the 2024 campaign. It was about the coverage 30 years ago of President Bill Clinton and questions surrounding his role in an Arkansas real estate deal known as Whitewater. (The Post columnist was my father, Richard Harwood, NF ’56.)

As the U.S. barrels toward a defining election in November, confusion over the news media’s role in American life has only deepened.

That’s partly been in response to an 81-year-old Democratic incumbent who has presented a confounding blend of governing success and declining abilities. But more profoundly, the press has struggled with its approach to Trump, the Republican Party’s nominee for the third consecutive election cycle.

As is by now so familiar as to be a cliche, America has never seen a presidential candidate like Trump. Experts warn his brazen dishonesty exceeds that of any of his predecessors. And the threat he and his allies pose to the norms, freedoms, and institutions of the world’s most powerful nation lends extraordinary gravity to the collective decisions of the news business.

Is the paramount responsibility of U.S. journalists to help protect their country’s 2½-century-old democratic experiment, which not coincidentally also protects the existence of their craft? That requires braving the ire and denunciations of Republicans long conditioned to scream bias.

Or are journalists obliged to preserve the approach that emerged as their 20th century standard, striving for neutrality by treating the candidates and their parties as roughly comparable forces deserving roughly comparable scrutiny? That enrages Democrats who insist that equating both sides is false and misleading.

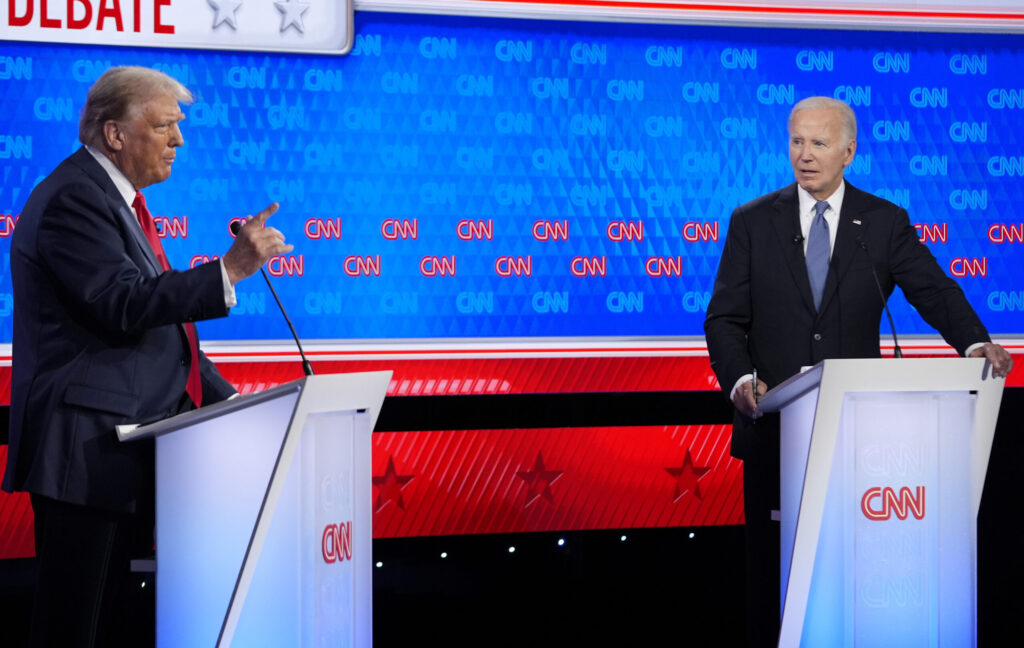

The tension between those competing views simmered for more than a year before boiling over after the June 27 presidential debate. Digital-age financial pressures and the altered contours of the media landscape have complicated the situation.

The dilemma defies easy answers because both perspectives can lead to uncomfortable extremes. Elevating democracy raises the question: Should a reporter actively promote the candidate committed to preserving it? But elevating neutrality, and passively watching an authoritarian gain power, could unravel the press freedoms woven into the fabric of the U.S. since its founding. Different journalists, sometimes gingerly, walk different paths.

Biden’s faltering performance against Trump, after years in which Republicans painted him as enfeebled — or even senile — triggered a torrent of coverage questioning his ability to seek reelection, much less serve as president for another four years. In the week following the debate, former television journalist Jennifer Schulze counted 192 stories in The New York Times concerning Biden’s age. She found fewer than half as many stories on Trump, even though the period coincided with a Supreme Court ruling that he may be granted immunity from criminal prosecution for “official acts” during his time in office.

The preponderant focus on Biden’s fitness rather than Trump’s license to break the law left the former president in a commanding political position. The critiques by Democrats and the resulting press-driven furor, Democratic pollster Mark Mellman says, hurt Biden more than his debate performance itself.

That exacerbated the sense of alarm among media critics who consider it self-evident that Trump’s threat to America’s constitutional democracy stands above any other issue. After the 2020 presidential election, the U.S., for the first time in its nearly 250-year history, faced a defeated incumbent who not only falsely claimed he had been reelected but also sought to undermine the constitutional process of ratifying the voters’ will, urging his followers to “fight like hell” before they stormed the Capitol.

Trump has not renounced what he did. Rather than condemn those convicted for their roles in the Jan. 6 insurrection, he has held out the prospect of pardoning them. He acknowledges the possibility of more violence after this election and vows “retribution” against political enemies if he returns to the White House.

His behavior underlies the call by New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen for the press to resist the familiar temptations of horse race coverage and to emphasize “not the odds, but the stakes” of the 2024 election. Trying to preserve an appearance of balance in the coverage, say veteran political scientists Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein, would actually be a disservice because “a balanced treatment of an unbalanced phenomenon distorts reality.”

To skeptics, that sounds like a call to unabashedly favor Vice President Kamala Harris — who became the Democratic nominee after Biden eventually heeded calls to step aside — as a matter of national survival. Among other prominent voices, foreign policy expert Richard Haass, who played key roles in two Republican administrations, says flatly that the Democratic ticket “has to win” to sustain the American experiment and thwart Trump’s vision of “Budapest on the Potomac.”

That was too stark a framing even for Biden when he remained in the race. “Not if you put it like that,” the president told me in an interview last fall; instead, he said he’d simply emphasize the dangers of Trump’s stated intentions.

The nation’s leading newspaper rejected the democracy-above-all-else approach out of hand. In an interview with the digital outlet Semafor, New York Times executive editor Joseph Kahn suggested that such a framework would compromise the very norms its advocates aim to preserve.

“To say that the threats [to] democracy are so great that the media is going to abandon its central role as a source of impartial information to help people vote — that’s essentially saying that the news media should become a propaganda arm for a single candidate, because we prefer that candidate’s agenda,” Kahn said.

“It’s our job to cover the full range of issues that people have,” he added. “At the moment, democracy is one of them. But it’s not the top one — immigration happens to be the top [in opinion polls], and the economy and inflation is the second.”

Kahn later clarified his comments, promising more coverage of issues around democracy and the expected thrust of a new Trump presidency. But the controversy generated by his remarks laid bare the dilemma American news executives face.

Elevating neutrality, and passively watching an authoritarian gain power, could unravel the press freedoms woven into the fabric of the U.S. since its founding.

In fact, neither the Times nor other major outlets have ignored the threat to democracy. Trump’s vow to be a “dictator for a day,” the criminal prosecutions of his allies in the scheme to count “fake electors,” and his plan to seize greater personal control of the government bureaucracy have all drawn significant attention. In the case of Project 2025, the radical right-wing agenda prepared in part by some of his close advisors, news stories later amplified by Democrats produced a storm intense enough that Trump disavowed the blueprint.

“I think we’ve done, honestly, more than anybody else” to point out Trump’s intentions, Kahn told The New Yorker. “And we’ll have more to come. One of the things we’re trying to do with the packaging of this is to make some of that really impactful reporting on Trump, and the people around him, and his agenda for 2025, more present in the report throughout the campaign, rather than relying on people to search into the background to get it.”

But Kahn’s explanation of coverage priorities in his Semafor interview raised its own questions. One is why journalists should organize their coverage based on opinion surveys. The second is whether some of their coverage has misshapen public opinion itself.

On the important public concerns of immigration, the economy, and inflation, Republicans have hammered the Biden administration relentlessly ever since he took office. Yet today it’s hard to find polls reflecting the reality that border crossings have plummeted in recent months, that inflation has declined sharply after spiking worldwide as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, and that the U.S. economy remains the strongest among Western countries.

Rates of violent crime, another favorite Republican target, have also declined on Biden’s watch. The media has given greater attention to the problems and their political consequences than to progress in addressing them.

In part, coverage that foregrounds political attacks, exaggerates danger, and downplays improvement reflects the familiar predilection for negativity that may be the most powerful journalistic bias of all. The aphorism, “if it bleeds, it leads” applies to broadcast news and print journalism alike. Bad news sells better than good.

And sales — measured in TV ratings, subscriptions, and clicks — matter more to news executives today than in decades past. The digital revolution has shattered the business model for news outlets that once enjoyed large audiences and dominant positions within their markets.

The scramble to restore or replace shrinking advertising and subscription revenue adds an air of desperation to media coverage choices. No less than democracy, journalism faces an existential threat of its own.

Every news executive knows that Trump’s dark flamboyance attracted bigger audiences than Biden’s drama-free competence. “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” the network’s then-CEO, Les Moonves, crowed during the 2016 campaign. Drops in audience after Trump’s presidency have led to layoffs at news networks and newspapers alike.

That doesn’t mean news managers have purposefully set out to help the candidate who seems better for business. But those realities loom in the background.

Further complicating journalistic incentives are changes in the structure of the news business. Smaller platforms occupying distinctive niches, ideological or otherwise, have largely supplanted the broad outlets of earlier generations whose constituencies spanned the political spectrum.

Following the profitable tumult of the Trump presidency, outlets bruised by accusations of unfairness have sought to demonstrate that they could be as tough on Biden as they were on his predecessor. And it’s not just because of pressure from the political right. Disdainful of the aged moderate in the White House, younger journalists have clashed with tradition-minded senior editors at legacy news organizations from the left.

The New York Times didn’t hide its exasperation that Biden, alone among recent presidents, had not granted its reporters an interview. The White House press corps, which had long complained about the paucity of Biden news conferences and interviews, reacted to the June 27 debate against Trump by suggesting that the president’s aides had deceived them about his condition.

Even before the debate, news coverage focused far more on the mental acuity of the incumbent than that of his more entertaining rival. In a study of five leading U.S. newspapers — The Washington Post, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today — the liberal group Media Matters for America counted 144 articles on the candidates’ mental acuity in the period from Jan. 15 to June 17, 2024. Two-thirds of the stories focused exclusively on Biden.

Just seven percent focused exclusively on Trump, who is only three years younger. Biden’s departure in favor of the 59-year-old Harris leaves Trump, 78, as the oldest presidential nominee in U.S. history. Despite his penchant for bizarre, nonsensical, dishonest rants, the ex-president’s fitness has not provoked comparable media scrutiny.

The issues 2024 has presented are not entirely novel. A meandering debate performance in 1984 by Ronald Reagan, then the oldest president in American history at 73, ignited a brief flurry of stories about his fitness to continue in office. But a clever quip by Reagan curtailed it, and a few weeks later he won reelection in a landslide.

A decade earlier, crimes and dirty tricks by Republican President Richard Nixon and his aides undermined the integrity of American democracy. The Washington Post led the way in exposing them after the June 1972 burglary of Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel.

Criminal convictions sent Nixon’s former White House chief of staff and attorney general, among others, to jail. Nixon himself resigned in August 1974.

Then as now, angry Republicans railed against the perceived bias of major newspapers, magazines, and television news networks that they labeled the “Eastern liberal press.” Today’s Republicans complain about “fake news” from the “mainstream media.”

But 21st century politics have brought vast differences in degree, if not in kind. The scale of Trump’s deceitful self-seeking has no precedent in U.S. history. The Washington Post calculated that he made 30,573 false or misleading claims during his presidency. At a news conference Trump gave in August, NPR counted “162 misstatements, exaggerations and outright lies in 64 minutes. That’s more than two a minute.” Sycophantic members of Trump’s party have adopted his false claims about the 2020 election en masse.

“He not only has a dreadful record himself, he normalized lying in the Republican Party,” wrote Bill Adair, the journalistic innovator who popularized fact-checking as a staple of political coverage, in his forthcoming book, “Beyond the Big Lie.”

“Members of Congress and a frightening number of state and local officials,” Adair continued, “have adopted his disdain for the truth.”

Trump hasn’t changed against his new opponent. Yet when he asserted preposterously that the biracial Harris had recently decided to “turn Black” for political advantage, some headlines cast it as her problem rather than his.

“Harris faces a pivotal moment as Trump questions her identity,” The Washington Post declared. The New York Times asked: “Should Harris talk much about her racial identity? Many voters say no.”

Republicans grouse that Harris has climbed in the polls on the back of a friendly media. But to prominent press critics, some of the coverage has had the effect of legitimizing Trump’s smears rather than dismissing them as demagogic nonsense.

“The coverage of Trump’s attacks on Harris’s racial identity is a good example of the media once again allowing his bullying and false accusations to drive the narrative,” Margaret Sullivan, who served as a media critic at both The Post and The Times, told me. “Often the problem is not the number of stories, but about tone and framing. We’ve seen it before — all too often — and yet it keeps happening.”

So long as Biden insisted on remaining in the race, the incessant media narrative about his fitness boosted Trump’s position. But Biden’s decision to yield to the pressure had the opposite effect. Immediately after claiming the nomination for herself, Harris surfed a wave of Democratic unity and euphoria that lifted her above Trump in polls and election betting markets.

The home stretch ahead will determine whether she can ride that wave to the White House. If she does, American journalists may have safeguarded their country’s democracy without ever clearly deciding to try.