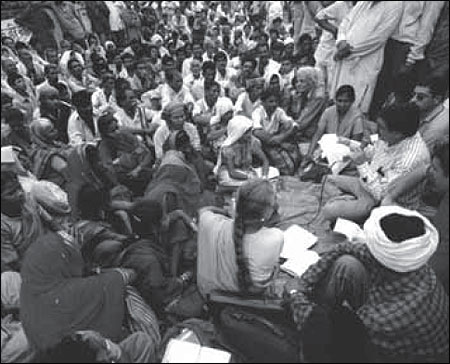

At a protest in Indore, India, people gathered to try to save land and homes from being flooded by a massive dam project. The protest resulted in some modest concessions from the government. Photo by Robert Dawson, © 2001.

As a young reporter in Vietnam three decades ago, I occasionally amused myself by comparing Saigon and Washington reports on the same war event. It was bitter amusement, to be sure. Inevitably, the stories with a Vietnam dateline were more accurate: The Washington stories rippled with errors and misinterpretations because their authors were so far from the developments they described and alarmingly dependent on manipulative and mendacious sources.

Part of my attraction to narrative journalism is that it’s the antithesis of long-distance reporting: It celebrates immediacy and intimacy and abhors abstraction—the only ones it allows are grounded in the concrete.

From the time I began to read seriously, in my teens, narrative nonfiction held the tightest grip on me. I adored books and essays by its eclectic crew of practitioners—including Gay Talese, George Orwell, Norman Mailer, E.B. White, Primo Levi, Joan Didion, and John McPhee. But it still took me a couple of decades after Vietnam before I committed the act myself. I’d gotten comfortable with the reliable but pallid voice of standard journalism and kept telling myself I’d write narratives as soon as the chance arose. At last, in my 40’s, I realized I had better stop waiting to be asked.

I hung out in a local shoe repairman’s shop for a few weeks and spent nearly as much time in a barbershop. The two stories I wrote were never published, but I learned techniques that I could apply to larger subjects and experienced what felt like the firing of my mind’s creative synapses, surprising and overdue all at once. I attended a writing conference, where I was shocked to hear my prose harshly criticized, and realized I’d overlooked some basic narrative techniques. (“Write in scenes” is the instruction that hit me with the force of a commandment.) As I kept writing, a lyrical voice, which had previously surfaced only in letters, gradually emerged. At Wired, where I wrote regularly, I declared that henceforth the only stories I would write would be narratives—and, to my surprise, was immediately assigned them. My narrative career took flight.

Choosing Characters

In a long piece I wrote for Harper’s about global water scarcity, I interspersed narrative and exposition. I’d taken on the elemental subject of water, but the piece still felt like a view from the shore: To immerse myself, I’d have to write a book.

At the core of every debate about water are dams, the modern pyramids, generators of extravagantly apportioned electricity, water storage, and environmental and social disasters, where water conflicts are manifested in most dramatic form—I knew dams were my subject. At first I became intrigued by the ambitions and tribulations of the shortlived but influential World Commission on Dams. The commission arose out of the World Bank’s frustration in building dams, when the bank found many of its projects stalled by protests: In an act of seeming desperation, it agreed to support an independent commission of leaders from every dam constituency that would review dams’ performance and provide guidelines for how they ought to be built in the future.

One of the commission’s 12 members was Medha Patkar, the world’s foremost antidam activist, who during a decade and a half of protest over a dam in Western India had tried drowning herself in rising reservoir waters (only to be wrested away with water at neck level by police intent on avoiding an embarrassing incident) and went on hunger strikes of 26, 22 and 17 days. Far across the dam divide was Jan Veltrop, a Dutch-born, naturalized-American past president of the dam engineers’ trade group, the International Commission on Large Dams, who had helped design the most voluminous dam in the world, Pakistan’s Tarbela, with 40 times the volume of the Great Pyramid. From its formation to the issuance of its final report two-and-a-half years later, the commission overcame numerous crises to produce a unanimous report with 26 best-practice guidelines for dam construction. The World Bank, dismayed at being told what it didn’t want to hear, labeled the guidelines excessive and rejected the report. The commission’s story was a skirmish in the ongoing war of environment, development and globalization, and I thought it deserved to be told.

I confess that I did not at first envision the book as a narrative. In fact, I was on the verge of signing a contract that would have committed me to write a commission history when Paul Elie, an editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, suggested I try approaching dams in narrative form, by focusing on a few key figures in the debate. As soon as he said it, I knew that was what I wanted to do, and I realized the World Commission on Dams provided the structure. To foster a balanced commission, its organizers sorted nominees for commissioner into three categories—pro-dam, mixed and antidam—and selected four commissioners from each. For roughly equivalent reasons, I did something similar: I chose as subjects one commissioner from each group.

The three people I chose were an Australian water manager, struggling to reverse the grave decline of the continent’s only major river system, the Murray-Darling; an American anthropologist considered the world’s foremost authority on dam resettlement who’d spent nearly half a century studying the calamitous impact of a dam on 57,000 displaced people in Africa’s Zambezi River Valley, and Patkar, the Indian firebrand. With the shift from one commission history to three commissioner narratives, I felt freed. Now, among other things, I could turn a startling but opaque statistic—that at least 40 to 80 million people have been displaced by dams, usually with disastrous consequences—into stories with flesh and bones.

Once I got started, I realized how fortunate I’d been to escape writing a commission history. The 100-plus principal actors in the dams’ debate were spread all over the world, as were the dams themselves. I would have lacked the money and energy to visit all of them, and since I’d hadn’t witnessed most commission events, I would have had to rely on others to reconstruct them—I’d have been deprived of the use of my senses. Even if I succeeded in cobbling a history together, the opus would have struggled to overcome the drear emotions inspired in readers by the word “commission.”

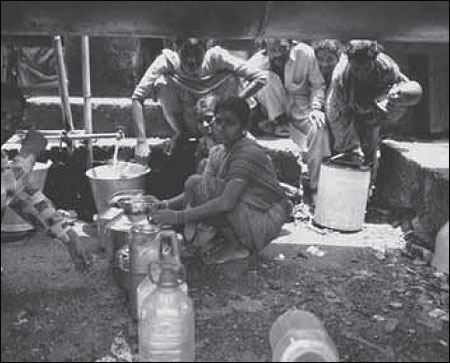

People live under a large pipe in Bombay, India, where they illegally tap into it to get water for their families daily use. Photo by Robert Dawson, © 2001.

Gathering Stories

Instead, I visited Patkar’s remote monsoon outpost, where she was once more planning to drown herself, and waited with her for rising reservoir water to inundate her hut. As it happened, the water never threatened the hut in what turned out to be a poor monsoon year. But it was hard to think of that as something gone wrong, and nothing else on the trip did. With half a dozen of Patkar’s coterie of supporters I slept on the ground in her hut and traveled with her to demonstrations and watched her try to convey her Gandhian/Chomskian/ feminist/Mother-Teresian/antiglobalization worldview to bewildered tribal people who faced watery eviction from their mountain plots.

In Mumbai, I visited the posh home of Patkar’s mother, who complained that on her occasional visits home Patkar spent all her time on the telephone, organizing and pointed out to me the spot on the living room floor where Patkar, eschewing a bed, insisted on sleeping, beneath a giant-screen Sony. The trip felt effortless, like a gift: Each leg yielded a vivid chapter in a tale that unfolded like a novella. When Patkar held a protest in front of a government office in the town of Indore, 300 of her impoverished tribal supporters traveled to it by taking a five-hour boat-ride, an hour-long hike, and a 10-hour overnight drive on rutted roads while standing in the back of two trucks. The astounding, saddening, largely futile protest lasted seven hours, and I knew as I watched it that it provided my ending. It is the India section of the book that won the 2002 J. Anthony Lukas Work-in-Progress Award.

Deluded by the seeming ease of the India section, I briefly entertained the notion that the other trips would automatically deliver up equivalent dollops of drama and story structure. Africa and Australia disabused me of that idea, if only because the two principals’ lives lacked the high-wire drama of Patkar’s. My editor suggested focusing less on the personalities, more on the rivers and dams. It was good advice.

Thayer Scudder, the anthropologist, began his career in 1956, when he studied the Gwembe Tonga, people who’d lived for centuries along the Zambezi River in what is now Zambia and were about to be resettled to infertile land because of the construction of what was once the largest dam in Africa, the Kariba Dam. Every year or two since, Scudder or his colleague Elizabeth Colson visited the Tonga resettlers and traced their resulting social disarray in books and papers. I went with Scudder to notable dam projects in Lesotho and Botswana, and I visited the Tonga on my own: Their most recent crop had been a 100 percent failure, and some were waiting to die. (Government and charity aid later staved off starvation.)

In Australia, I was beguiled by the eucalyptus-bordered Murray, the arid continent’s only major river, the main stem of one of the world’s 15 longest river systems but with less flow in a year than the Amazon in a day. Dams and other diversions have taken so much water from the river that the flow at its mouth now is little more than a quarter of its predam size, and the river and its surroundings are slowly dying. First, I watched as Don Blackmore, the hugely capable chief executive of the government agency that manages the Murray, negotiated among politicians, farmers and environmentalists to arrive at the culminating achievement of his career—a policy requiring farmers to relinquish some of their water so that the river can survive. The agreement Blackmore secured in October 2003 was unprecedented in providing for the return of farm water to the river, but the small quantity involved will almost certainly not be sufficient to halt the river’s decline.

The agreement solidified Australia’s reputation as the leading water-managing country in the world, but it also suggested the weakness of the field. Blackmore’s maneuvers provided the story line, but the stately river in the continent of extremes was still missing. Thus, on a second trip, I drove from one end of the river to the other, from the sleek, monumental Dartmouth Dam near the basin’s crest to the astonishing, depleted Coorong lagoon at the nearly imploded Murray mouth. Along the way I talked with farmers, fishermen, Aboriginals and environmentalists and saw the river from enough vantage points to realize that more than Blackmore, the Murray was the main character in the tale.

Writing Stories

“Write lyrically” was another of my editor, Elie’s, instructions, more easily commanded than done. Yet for me, the pleasure of writing narrative arises from the way it facilitates a robust voice: Much more than standard journalism, it rewards spontaneity, suppleness, playfulness. A tiny example: Long before I finished the book, I chose the title “Deep Water” in reference to both the depth of mega-dam reservoirs and the trouble that dams cause. Then, as I wrote the book’s last paragraph, I found myself describing a wide, artful circle of stones protruding out of the ebbing Coorong lagoon. It was an ingenious Aboriginal fish trap, abandoned but still intact, which had relied on high tides to bring fish within its perimeter and low tides to trap them behind the stones. The Aboriginals were driven from the Coorong seven decades ago, and the lagoon’s fish population nosedived after European settlers placed barrages, dams and weirs across the upstream river.

“The Coorong has lost nearly everything,” my last sentence began, “but the trap remains intact, as if awaiting the return of fish, the return of the Murray…”—and what? The sentence’s rhythm demanded a third returning entity. It took a day or two before my Eureka moment arrived: “…the return of deep water.” In reiterating the title, I discovered its most important meaning: rich, nutrient-bearing water, whose dam-induced absence is one of the book’s themes. The imperatives of narrative nonfiction carried me like a current to the book’s last words.

Jacques Leslie’s book on dams, rivers and people, “Deep Water: The Epic Struggle Over Dams, Displaced People, and the Environment,” will be published in September 2005 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.