When Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, the journalists of the English-language Kyiv Independent set up a live blog with constant updates for Ukrainians and readers around the globe. Their earliest dispatches described skirmishes in the Pobeda and Glukhiv districts, announced the first-day death toll of 137, and published President Volodymyr Zelensky’s call for governments around the world to impose crippling sanctions on Russia.

It was the kind of fact-based, comprehensive coverage of the Russian military threat that the site had been offering for weeks. Just days earlier, defense reporter Illia Ponomarenko fielded a reader’s question about whether Ukraine had sufficient air defenses in case of a Russian attack. “Oh, no, we don’t, I’m afraid we don’t,” replied Ponomarenko in a podcast interview. “I think it’s safe to say that we are pretty weak.” The fighter jets Ukraine could use in a battle with Russia, he noted, dated back to the Soviet era, more than 30 years ago.

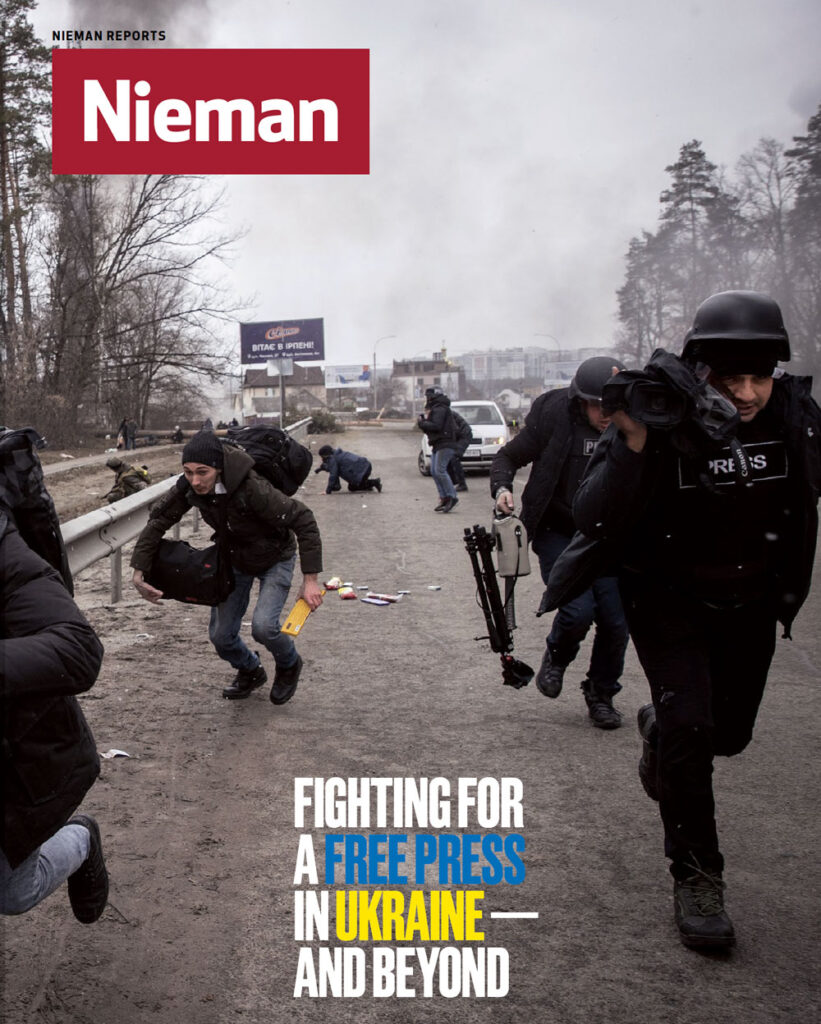

Despite being outnumbered by better equipped Russian forces, the Ukrainian military — and a growing contingent of determined civilians — fiercely resisted the invasion. The Kyiv Independent, Ukrainska Pravda and a clutch of other Ukrainian news outlets have continued to report the war with a dogged devotion to truth-telling — despite themselves being targets of the Russian military. They have been documenting the plight of thousands of Ukrainians taking shelter in subway stations, the harsh conditions in the city Volnovakha where the bombardment has destroyed the power and water supplies, and how the Russians have been shelling residential areas.

Before the Russian invasion in February, Ukraine was part of a group of post-Soviet states — along with Moldova, Armenia, and Georgia — that have endured both authoritarian rule and periods when the press could be considered partly free, depending on who won the last national elections. These four countries have never achieved the broad freedoms and self-sustaining independence of media in former Soviet republics Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. But they also have not been squeezed into near extinction by the deeply entrenched dictators and autocrats who rule other former republics, where journalists are routinely jailed (Belarus and Azerbaijan), declared “foreign agents” (Russia), or have so little freedom that independent journalism never got a real foothold (most of the Central Asian republics).

These four countries have never achieved self-sustaining independence of media. But they also have not been squeezed into near extinction by the deeply entrenched dictators and autocrats

Journalism in these four “midway media” countries lies somewhere between the freedom of the Baltics and the authoritarianism of most other post-Soviet states. Their press freedoms fluctuate, their funding is in constant deficit, and the survival of their independence still relies heavily on foreign funding, three decades after the Soviet collapse. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is a powerful reminder of the vital work these journalists and their newsrooms do — and how precarious press freedoms are in the face of aggression from Putin and other authoritarian leaders around the world. Fears that Ukraine might only be the beginning of Putin’s territorial ambitions have put other governments and journalists on high alert. Among the midway media countries, Moldova and Georgia announced plans to apply quickly for European Union membership, as Ukraine has.

Here is a look at how the independent press is surviving in Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, and Georgia.

UKRAINE

Ukrainska Pravda is one of 10 independent news organizations that meet the “white list” high standards of balance, transparency and ethics of Ukraine’s nonprofit Institute for Mass Information. Much of the rest of the media in Ukraine is linked to billionaires, politicians, and politically connected figures who own dozens of television and radio stations, newspapers, and magazines. Many outlets are little more than oligarch mouthpieces.

As Russian forces push deeper into the country, it’s not clear how long, and in what conditions, these newsrooms will be able to continue to operate. U.S. officials have said that Russia has a list of Ukrainians, including journalists, to be killed or sent to detention camps if Russia occupies the country.

Related Reading

Call Out Bigotry in Reporting on the Ukraine Invasion

By Issac J. Bailey

Ukrainian Journalists Risk Everything to Stand Up to Putin

By Anne Garrels

That chilling claim did nothing to slow down the Ukrainian journalists delivering round-the-clock updates on Russia’s invasion, like the frank, well-sourced analyses of Kyiv Independent reporter Illia Ponomarenko. Until recently, Ponomarenko covered the military for the English-language Kyiv Post, whose loyal readers included diplomats, academics, and expats in the Ukrainian capital. The 26-year-old Post newsroom had a reputation for tough-minded coverage of the country and its politics — until the day last November when owner Adnan Kivan abruptly fired Ponomarenko and all his colleagues. The move by Kivan, a construction tycoon, was seen by staff as political retribution for its reporting on the government’s weak anti-corruption record.

The firings silenced Ponomarenko, just as Russia began its massive troop buildup at Ukraine’s borders. His fate, and the fate of his colleagues, might have gone down as yet another example of how business and politics too often combine to smother critical reporting in former Soviet states. But the story didn’t end there. Within weeks, Ponomarenko and about 30 other fired Post staffers were back in business — online, under the new name Kyiv Independent, and without a business-owner.

The Independent’s rapid startup was enabled by in-kind help from sympathetic Ukrainian businesses, by a nearly $100,000 grant from the European Endowment for Democracy, and by financial pledges from several hundred individuals inside and outside Ukraine. Speaking before Russia’s invasion, editor-in-chief Olga Rudenko said she wasn’t surprised by the outpouring of support: “We were very proud of the journalism standards that we uphold.”

In December, just a few weeks after the new site was born, its entire staff was honored with a “Journalist of the Year” award by Ukrainska Pravda, the country’s largest independent news site. The recognition of the startup by an established newsroom speaks to the unity and communal support that Ukraine’s independent journalists have mustered in times of crisis. And the public’s early support of The Kyiv Independent reflects high levels of audience trust. Since the Russian invasion began, GoFundMe campaigns like this one are raising hundreds of thousands of dollars to enable The Kyiv Independent, Ukrainska Pravda and other independent media to continue their work.

“Freedom of speech is still a big value for Ukrainian society,” said Sevgil Musaieva, editor-in-chief of Ukrainska Pravda, who also spoke to Nieman Reports before Russia’s invasion. The site was created in 2000 with a grant from the U.S. embassy in Ukraine, during then-president Leonid Kuchma’s rule, a period of heavy censorship and attacks on journalists. Publishing Ukrainska Pravda on the internet had been seen as a way around Kuchma’s repressions.

But a few months after the site began running investigative reports on government corruption, the beheaded torso of founder Georgy Gongadze was discovered in a forest outside Kyiv. Though investigations eventually led to some convictions, no one was ever charged with ordering Gongadze’s murder. Nor has the 2016 car bomb murder of Ukrainska Pravda journalist Pavel Sheremet been solved.

Through years of political turmoil, street revolutions, and the ebb and flow of press freedoms, Ukrainska Pravda has continued to investigate corruption in successive governments. Early this year, the site broke stories exposing one member of parliament from President Volodymyr Zelensky’s party for accepting a $20,000 bribe and another for attempting to bribe police. The parliamentarian who offered a bribe, caught on video obtained by the site, was quickly expelled from the party.

Since the Russian invasion began, Ukrainska Pravda has had wall-to-wall coverage of the fighting, detailing troop losses, civilian casualties, the roll out of sanctions, and the international response. Like many other outlets, Ukrainska Pravda’s survival depended on foreign donors for years, but the site now is financed largely by advertising, according to Musaieva. A new membership program also provides about 10 percent of the budget.

In some ways, Ukraine’s journalists are better prepared to cover the new Russian invasion than they had been when Russia took over Crimea in 2014

Even before the invasion and the GoFundMe campaigns it has inspired, the independent online community in Ukraine had greater financial strength than its counterparts in other countries, thanks in part to population. Ukraine’s 43 million people are more than 10 times the size of the populations of Moldova, Armenia, and Georgia. Whether this support holds — and what the media landscape will look like during and after the fighting — are unknowable.

Ukrainian news audiences also are more likely to sign up for subscriptions or media memberships, perhaps in part because of the high-profile role they saw journalists play in exposing corruption after the Maidan street revolution that sent President Viktor Yanukovych fleeing to Russia in 2014.

In May, Ukrainska Pravda announced its sale to Tomas Fiala, an investment banker who owns another popular Ukrainian news site, Novoye Vremya. Fiala signed a detailed agreement pledging he would not interfere editorially, and the purchase quickly enabled Ukrainska Pravda to hire several investigative reporters. And though the purchase by a rich businessman might sound like cause for alarm, particularly after the lockout at the Kyiv Post, Fiala “is not an oligarch,” said Musaieva. His business, Dragon Capital, “has no connection to state budget and to state companies” that would make him vulnerable to political pressure.

In some ways, Ukraine’s journalists are better prepared to cover the new Russian invasion than they had been when Russia took over Crimea in 2014. Back then, few journalists were trained to cover conflict, but in the last eight years that has changed.

But the Russian assault may pose the most ominous threat yet to Ukraine’s independent newsrooms. Russian attempts to take control of the Ukrainian capital could trigger widespread civil protests and make Ukrainian media a particular Kremlin target, predicts Gulnoza Said, CPJ program coordinator for the region: “The fight will be not just for establishing power in Kyiv or in newly invaded territories, but also for the hearts and minds of people in Ukraine.”

MOLDOVA

In 2004, Alina Radu and a journalist friend set out to create a weekly investigative newspaper in the former Soviet republic of Moldova. They scraped together money for a design and layout computer. But stories were written on four jury-rigged desktops, cobbled together by Radu’s engineer husband from a local bank’s cast-off computers. New desks? Too much of a luxury, Radu decided, so the newsroom of Ziarul de Gardă (ZdG, or “Newspaper on Guard”), was furnished with borrowed tables and chairs.

Such humble surroundings were not what Radu was used to. For more than a decade, she had worked in well-resourced Moldovan newsrooms, starting with the state TV channel and later a privately-owned TV company. She left both jobs when politicians started dictating what journalists should write.

Her third reporting post was at a weekly paper that eventually became Moldova’s first privately-owned daily. “It was beautiful,” says Radu. “We did a lot of courageous, critical journalism.” But that ended just like her earlier jobs when the owner — a member of parliament — issued strict orders on covering upcoming elections.

Finally, at ZdG, Radu and her colleagues were in control. No one would tell them what to write, or how to write it. “When we started, we were so happy,” she says. “We are free, yes, we had all the freedom.”

There was just one problem: They didn’t have any money.

Radu had run up against the existential challenge that has threatened independent journalism for three decades since the official collapse of the Soviet Union. In Moldova, as in most of the 15 former Soviet republics, advertising and subscription revenues have rarely provided a survival budget, and the wealthy politicians or businessmen with money to invest in media demand editorial control in return. In the end, ZdG — like so many other independents — got a financial lifeline from foreign funders eager to help democratic norms and independent media thrive across the region.

Back in 2004, ZdG survived first on a six-month grant from the Romanian government, then another from the U.S. After that, says Radu, “I just learned to apply everywhere” — the Canadian embassy, media institutions in Amsterdam, public and private donors in the United Kingdom and France. Those funders have kept ZdG in business, investigating the corruption that is often defined as endemic in this midway media country — corruption that is routinely exposed by Moldova’s small, independent journalism community.

Many corruption stories carry the bylines of journalists from ZdG or the investigative site RISE Moldova, founded in 2014. Newer independents that pursue some investigative reporting include Agora, Cu Sens, and the Russian-language NewsMaker. But independent journalism is practiced in only about 15 percent of Moldova’s newsrooms, according to a 2019 report by IREX, a Washington-based non-governmental organization. The other 85 percent “serve the governing forces or political parties, not the public interest,” says IREX.

The 85 percent have been “captured” over the years by politicians or their wealthy allies, a process that began in Moldova and other former Soviet republics soon after independence in 1991. Today nearly all TV channels, where many Moldovans say they get their news, are owned by politically aligned companies or directly by the politicians themselves. Two of those media owners also control the vast majority of the country’s advertising market, steering business to their TV stations through what competitors charge amounts to a cartel.

With a population of less than 3 million and an economic rating as one of Europe’s poorest countries, Moldova has a small ad market to begin with. With much of that market under political control, independent newsrooms can count on little support from advertising. NewsMaker, for example, makes only about 20 percent of its budget from ads, says Galina Vasilieva, editor-in-chief of the seven-year-old independent site. The rest comes from foreign funders such as George Soros’s Open Society Foundations and the U.S.-funded National Endowment for Democracy.

“All independent media [in Moldova] are funded through international funds,” says Vasilieva. “We can’t exist without these funds.”

Though it translates some stories into Romanian, which most Moldovans speak, NewsMaker’s target audience is the country’s Russian speakers, including those living in Transnistria, a secession-minded region that lies on the border with Ukraine and maintains some political autonomy within Moldova. (Russian soldiers have long been stationed there, and there is widespread concern that Putin might also seek to annex the territory as part of his attack on Ukraine.) Russian trolls and Kremlin-financed media bombard Transnistria’s largely Russian and Ukrainian population with propaganda and disinformation; NewsMaker promotes itself as an alternative, promising, “We don’t distort reality.”

A new government can promise reforms, but “no matter what government comes to power, investigative journalists continue to do their work,” Cepoi says

NewsMaker, ZdG, and several other independent outlets are part of a project run by the international NGO Internews, aimed at reducing reliance on foreign funding by building audience and audience support. ZdG, for example, has expanded its reporting beyond investigations, updating the site throughout the day with breaking news, analysis, and videos. Editor Radu says that has made ZdG’s website one of the top five audience destinations for news and enabled it to start a sustaining membership campaign with about 200 supporters. That support — along with kiosk sales of a ZdG print version, some online advertising, and income from selling commercial services such as photography — has reduced the foreign aid share of the budget from 100 percent to 70 percent.

“The model now is to have a little bit [of income] from everywhere,” says Corina Cepoi, the Internews country director for Moldova.

RISE Moldova, another partner in the Internews project, says 90 percent of its funding comes from foreign donors, some through its partnership with the nonprofit Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. RISE worked with OCCRP journalists in 2014 to help expose the involvement of Moldovan bankers and judges in an elaborate Russian money-laundering scheme. More recent RISE stories, about former president Igor Dodon’s frequent meetings in Moscow with a Kremlin office “established to oversee and guide the Socialist Party leader,” were credited with helping current president Maia Sandu defeat Dodon’s Socialist Party.

Sandu was elected last July with the strongest anti-corruption mandate of any post-independence Moldovan government. That’s raised hopes among journalists that their years of documenting official malfeasance will lead to serious legal reforms and prosecutions. While they wait to see what the new government delivers, independent journalists are also at work scrutinizing its top officials. Already, they’ve questioned offshore holdings and wealth reports by some in the Sandu government.

The message is clear, says Cepoi. A new government can promise reforms, but “no matter what government comes to power, investigative journalists continue to do their work.”

ARMENIA

In 2000, the Washington-based International Center for Journalists brought a group of Armenian journalists to the U.S. for a three-week tour. The Armenians attended the annual conference of Investigative Reporters and Editors, visited 60 Minutes and other newsrooms, and learned the tools and techniques of investigative reporting from seasoned American practitioners. “I think the main purpose of the organizers was to inspire us,” says Gegham Vardanyan, who was a young reporter at a popular independent Armenian TV channel when he was chosen for the U.S. trip.

If inspiration was indeed the organizers’ goal, it worked. Not long after Vardanyan and the others returned home, several of them began talking about creating a new venture: a nonprofit newsroom devoted exclusively to investigative reporting. By 2001, inspiration became reality when Hetq (“Trace”) Online was launched.

The news landscape in Armenia is typical of the midway media countries: a handful of foreign-funded outlets forms a tiny archipelago of independent journalism, surrounded by a sea of bare-knuckled, highly partisan media

Two decades later, Hetq’s site draws over 200,000 visitors a month, according to Google Analytics, for stories about the sex trafficking of young Armenian women in United Arab Emirates, exposing a cybercrime ring, and revealing corruption at all levels of government. Some stories have had significant impact, such as winning reversals of corrupt sales of public kindergarten buildings and public forest lands. Other Hetq investigations have had another kind of impact: physical, verbal, and cyberattacks on Hetq and its journalists.

Despite its successes, Hetq continues to rely on foreign donors for 90 percent of its budget, according to deputy editor Liana Sayadyan. Those donors include the European Union, individual E.U. governments, and U.S. entities such as the National Endowment for Democracy, many of which also underwrite two other independent outlets in the country, Civilnet and EVN Report. EVN is named for the airport code for Yerevan, the Armenian capital. It began as an English-language site, targeting the estimated seven million Armenians and their descendants living in the diaspora. Both Civilnet and EVN emphasize political analysis and features, more than breaking news.

Three million people live in Armenia, where the Armenian-language service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty is popular with audiences seeking balanced breaking news reporting. “Balance” can be dangerous, though, as RFE/RL journalists learned in 2020, when new fighting erupted in Armenia’s 30-year-old conflict with Azerbaijan over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Both governments regularly claimed their side was winning. While most local media ignored Azerbaijan’s claims, RFE/RL reported what each country said, earning threats and even physical attacks from an angry Armenian crowd. “We think people have a right to know what the other side is saying,” says RFE/RL reporter Artak Hambardzumyan. “But if you report anything from the Azerbaijani side, you are becoming the enemy.”

The news landscape in Armenia is typical of the midway media countries: a handful of foreign-funded outlets forms a tiny archipelago of independent journalism, surrounded by a sea of bare-knuckled, highly partisan media — particularly on the 20 TV channels that reach national audiences or those in Yerevan.

Perhaps the best-known practitioner of this bare-knuckled “news” is Armenia’s current prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan. Before he led the 2018 “velvet revolution” that catapulted him to high office, Pashinyan worked at several flamboyantly oppositionist tabloids, including a long stint as editor-in-chief of Haykakan Zhamanak (“Armenian Times”).

When Pashinyan took to the streets in 2018 with his political grievances against then-president Serzh Sargsyan, television stations — virtually all of them controlled by the government or its supporters — ignored him. And that might have been the end of Pashinyan’s protest, but for the livestreams of independent journalists. Their online coverage prompted a genuine political uprising, until the street crowds grew so large that they forced Sargsyan’s resignation.

Any gratitude Pashinyan might have felt for that 2018 media coverage is long forgotten. As prime minister, he lambastes Armenia’s media as “a garbage dump” full of ‘fake news’ and corrupt journalists. His party has curbed journalist access to parliament and reinstated criminal penalties for libel, a decade after Armenia eliminated them. “He tells people, ‘Don’t trust these corrupt journalists,’” says Shushan Doydoyan, a former radio producer who now heads the Freedom of Information Center of Armenia. And though Pashinyan’s anti-media rhetoric and actions haven’t reached the repressive levels of some of his predecessors, “He’s creating a very aggressive environment toward media.”

Three million people live in Armenia, where the Armenian-language service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty is popular with audiences seeking balanced breaking news reporting. “Balance” can be dangerous, though

Pashinyan’s rhetoric reflects the unvarnished, highly partisan language he wielded as a newspaper editor. In fact, say local journalists, Armenian audiences are now so used to consuming news presented from sharply partisan perspectives that many are puzzled by the efforts of RFE/RL, EVN, and others to be more balanced.

“We have a very politicized media field,” says Vardanyan, the TV reporter who went to the U.S. in 2000 and now edits a media monitoring site funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. “Polarized, politicized, with a lot of paid articles, with a lot of news websites, TV channels, taking sides,” he says. “I cannot say we have a healthy news field.”

To change that, Hetq’s editors aim to train more new journalists in the standards and techniques the site’s founders studied in their 2000 visit to America. A $322,000 grant from the U.S. embassy in Yerevan enabled Hetq staff to recruit non-journalists for a one-year program in investigative, data, and multimedia reporting. When the first two dozen students graduated in 2021, half got jobs in education or other non-journalism institutions, but several others went to work in media — including independent sites like Hetq, Civilnet and EVN.

But continued foreign funding — of the school and of newsrooms — is essential if the archipelago of independents is to survive and grow, says EVN managing editor Roubina Margossian. Her message to funders: “Make sure there are 10 more EVN Reports. Make sure there are 10 more Hetqs and Civilnet[s] and Radio Libertys.”

GEORGIA

Georgian media is often summed up in just two words: “pluralistic” and “polarized.”

If pluralism were purely a numbers game, then TV — where opinion polls show about three-quarters of Georgians go for news — would certainly fit the definition. The population of just under four million is served by nearly 100 TV channels.

But to hear more than one point of view, it’s necessary to channel surf — from the government-loyal programming of Imedi TV to the drumbeat of anti-government criticism on opposition channel Mtavari, whose website’s motto is, “Gain your freedom together with us!” (Mtavari has heavily covered the imprisonment and trial of Georgian opposition leader and ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili, who was arrested in October when he returned from exile.)

Georgian media is often summed up in just two words: “pluralistic” and “polarized”

The pluralist-but-polarized news on TV reflects Georgia’s operatic and often vengeful politics, in which the flamboyant Saakashvili and his United National Movement are pitted against the ruling Georgian Dream party of billionaire tycoon Bidzina Ivanishvili. “The media, especially TV, are perceived by parties as instruments of political struggle,” according to an October 2020 report by Transparency International’s Georgia office. That report accused Georgian Dream of launching politically-motivated legal actions against leaders of opposition TV channels — such as a “questionable investigation” of money-laundering charges against the father of the founder of TV Pirveli.

The report also documents verbal attacks on individual journalists (mainly those who work for opposition TV channels) who have been publicly denounced by Georgian Dream politicians as “immoral and unscrupulous,” “depraved” and “anti-state and anti-church.” The party’s politicians generally refuse to appear on opposition channels.

Georgia does have a handful of digital sites regarded as reliable sources of independent reporting, among them, on.ge, netgazeti.ge, and the English-language civil.ge. Dispatch, the sassy twice-a-week email newsletter put out by civil.ge, speaks with equal irreverence about Georgian Dream and its rivals. And when Tbilisi officials announced a doubling of bus fares to start in February, Dispatch proclaimed “Hell Getting Expensive,” the “hell” being the city’s notoriously poor bus service.

The Europe-based Center for Media, Data and Society reported in 2020 that without foreign philanthropy Georgia’s independent media would have developed ‘much less and at a much slower pace.’ The U.S.-based National Endowment for Democracy, one of several donors listed by civil.ge, is the largest foreign supporter of Georgian media, according to the report.

The online sites reach only small audiences but provide more neutral news and analysis than TV. “The biased editorial policy of broadcasters is reflected in their negative coverage of the political entities that they dislike,” according to a report by the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, a journalist-led monitoring group. In contrast, the Charter reported in an analysis of 2021 elections coverage, “Most online media display a high degree of editorial independence,” thanks in part to financial support from international donors.

Georgia’s public broadcaster, though perceived by some as pro-government, also strives for political neutrality; its Channel One is the only platform that got candidates from all parties to come together in face-to-face debate during the 2021 elections. In a country where TV news can look like a blood sport, her goal, says Director General Tinatin Berdzenishvili, is to provide viewers with “pure information without any analysis.”

Another outlet, the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Georgian service, has a reputation for evenhandedness — though it has to strike a balance without the actual on-air presence of Georgian Dream politicians, says Natia Zambakhidze, the station’s director. “They are not boycotting us, per se,” she says. “But they are not coming. They say, ‘Oh, we don’t have time. Not today, maybe tomorrow. Not tomorrow, maybe the day after tomorrow.’”

But when it comes to audience size, none of these outlets has anything close to the influence of the TV channels, whose owners are active in politics or openly sympathetic to one party or the other. And yet, in spite of their heavily politicized messaging, opposition channels such as Mtavari play a crucial accountability role in Georgia, says former journalist and media development specialist Tamar Kikacheishvili. Without them, TV news would be confined to the government’s version of events. “We wouldn’t know about important issues that are happening and affecting people,” such as the state of Covid-19 in Georgia or why the inflation rate is running in double digits, says Kikacheishvili. “To have Mtavari as a critical channel, it’s still very important, even though it’s not politically independent.”

Mtavari and other opposition channels also provide a platform for voices shut out of pro-government TV programming. That includes LGBTQ activists, whose planned gay pride rally last July was thwarted when demonstrators opposed to their cause filled the streets in Tbilisi. The anti-gay demonstration was covered by journalists from opposition channels and the public broadcaster, who became targets when the gathering turned violent. More than 50 journalists were assaulted, many of them needing medical care, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

In the days following the assaults, journalists launched their own protests, blaming the government for inaction against the anti-gay organizers. Though most of the organizers remain unpunished, Georgia’s opposition media is likely to continue pressing for action. Keeping the pressure on is important, says Kikacheishvili, noting: “If there is not this type of pressure, then we will get Belarus here.”