From Kashmir to Russia to Mexico and beyond, journalism is under threat. Reporters Without Borders estimates that nearly three-quarters of the 180 countries on its World Press Freedom Index either completely or partially block the work of newsrooms. The threats to journalists are physical, political and, especially under authoritarian regimes, increasingly existential. In our Reporting at Risk series,

Nieman Reports is publishing essays by journalists who are managing to do vital independent reporting — often at great personal risk.

Not long after Turkish lawmakers aligned with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s administration presented the parliament with a bill to criminalize disinformation in late May, a new wave of arrests targeting journalists was launched, underlining the government’s multi-pronged attempt to monopolize the right to decide on the “truth” ahead of the upcoming elections in June of 2023.

The Turkish bill is reminiscent of Russia’s “fake news” law, which criminalized reporting accurately on Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and triggered an exodus of journalists from the country. Ironically, some of those Russian journalists took refuge in Turkey, where Turkish reporters are now dealing with tactics similar to Putin’s in several ways.

Like Putin, Erdoğan has disabled the free press over many years. Erdoğan’s government passed “The Law Against Crimes Committed Through Publication On The Internet” in 2007, amending it in the following years to give authorities increasingly more power to block websites. In 2020, another amendment targeted “foreign social network providers with daily access of more than one million users,” saddling them with new obligations to the state, including the requirement to appoint a representative to Turkey and to respond to the privacy-based complaints from Turkish citizens in 48 hours. Meanwhile, Turkish penal code and anti-terror law have been used to jail or legally harass hundreds of journalists.

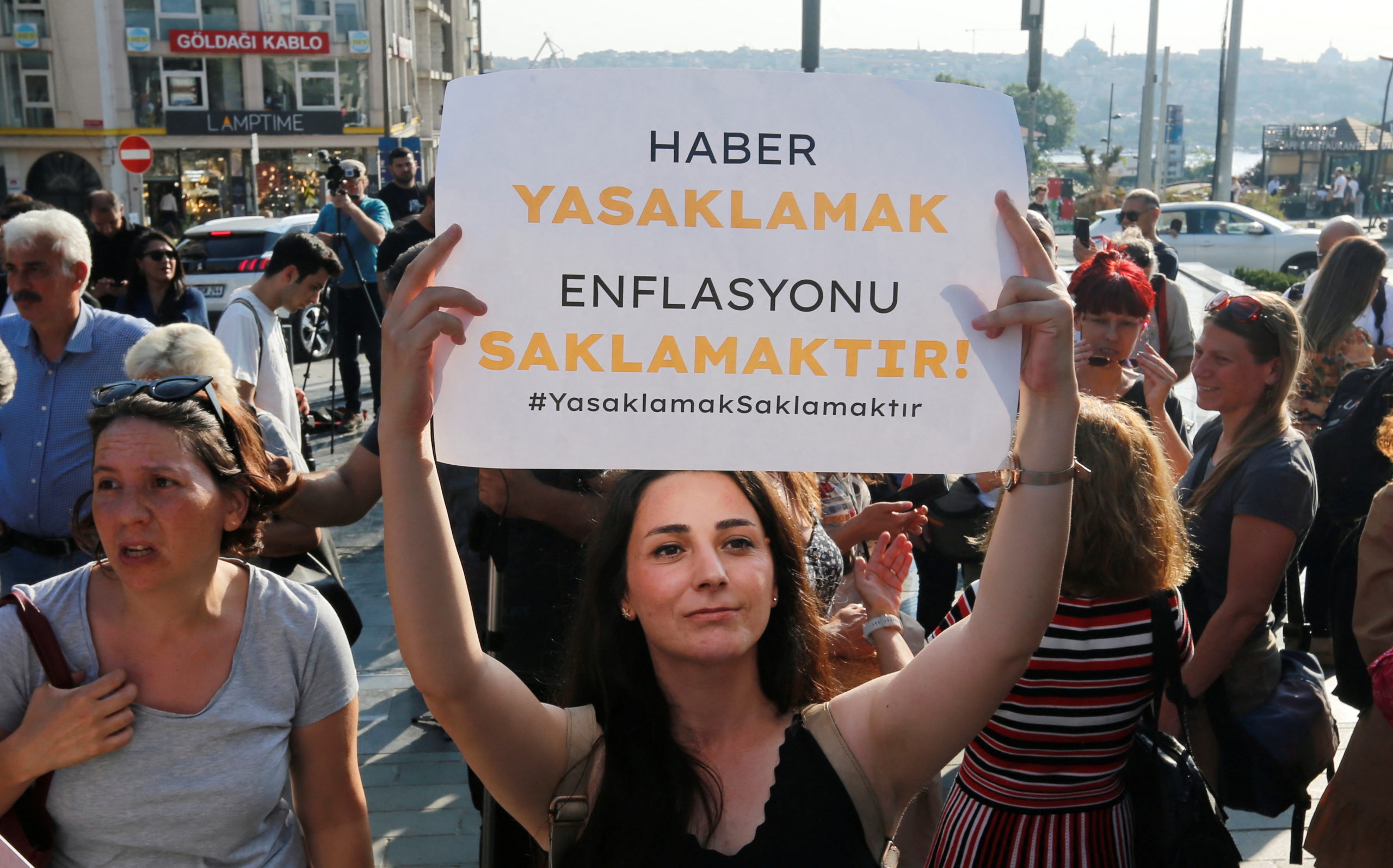

Still, the “disinformation bill” that Erdoğan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its ally Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) presented to parliament on May 26 is an unprecedented attempt to suppress journalism in Turkey. The seven leading journalism organizations based in the country voiced their concerns, warning that the bill “could lead to one of the heaviest censorship and self-censorship mechanisms in the history of [the Turkish] Republic.” A coalition of 23 international media freedom organizations stood in solidarity with Turkey’s journalists and called on the Turkish parliament to vote down the bill.

Another similarity between Erdoğan’s bill and Putin’s disinformation law is the vagueness in their wording. The Turkish bill uses broad concepts such as “disinformation,” “fake news,” “baseless information,” and “distorted information” without any legal definition. It also refers to elusive notions as “public peace” and “public order.” The courts are given the authority to make their own definitions and sanction individuals or media organizations over what they deem disinformation. This is especially dangerous in a country where the judicial system is captured by ruling politicians and has been repeatedly accused of abusing laws to penalize critical journalism.

Some of the new sanctions in the bill include:

- Criminalizing disinformation: Those who distribute what the government deems untruthful information publicly will be jailed from one to three years. If a source is quoted anonymously, then the punishment will increase by 50 percent. Although journalists are routinely put on trial in Turkey as terror suspects or for other causes such as defamation, the new law will give the authorities a more convenient tool to harass them over their reporting.

- Censorship by online refutation: News websites will now be recognized by the state as part of “the press.” Besides some marginal benefits, this step also means that these websites will be legally required to publish a refutation as newspapers do. In Turkey, refutations are used as a tool of censorship. In the past, Turkish news websites were ordered to take down content, such as corruption stories, dozens of times. With the new law, a digital news outlet that revealed a corruption case will not only be forced to delete its article but also to publish the refutation on the same hyperlink.

- Forcing social media companies to hand over personal data: Social media platforms will be required to hand over their personal user data to Turkish prosecutors and courts. If they resist, Turkish authorities will throttle 90 percent of the bandwidth reserved for the platform, which effectively means blocking the service in Turkey.

The government’s domination of conventional media, and particularly broadcast networks, helps it retain the popular support of its core voter base. In the run up to the 2023 vote, Erdoğan seems to be using the same tactics used by Putin and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán: warmongering (military threats against Syria and Greece) and populist economic policies that risk the future of the country for immediate political gain (an aggressive push for lowering loan rates and imposing rent controls).

This strategy can only work if the government has more control over the flow of information, and digital media present a source of disturbing leaks for Erdoğan. Last year, my colleague Burak Ütücü and I published original data in that showed the reach and engagement of independent online journalism outlets are catching up with the pro-government media machine. The Erdoğan administration’s latest moves against free speech in Turkey, including the disinformation law, are primarily designed as a new weapon against the rising tide of digital journalism at home and a new threat against technology platforms based abroad. In the coming months, the government — through the judicial system it fully controls — can use the disinformation law when it passes to arbitrarily decide what is true and what is not, sending more journalists and whistleblowers to jail.

Meanwhile, the government can use the same law to make companies like Google and Facebook work to its advantage. Our report, which was discussed extensively in a session of the Digital Platforms Commission of Turkey’s parliament in December 2021, also revealed that Google’s search algorithm heavily boosts Erdoğan’s media, hence boosting pro-government disinformation and hate speech, while suppressing independent journalism, despite popular interest. It seems that Big Tech’s commercial interests in Turkey trump the informational welfare of the democratic public.

The latest attempts at censorship aside, and regardless of the upcoming election results, independent journalism is alive and well in Turkey. Journalists — including many women, ethnic and religious minorities, the LGBTQI+ community, and younger reporters — keep reporting bravely in every corner of the country. They sometimes get jailed, harassed, and even murdered, but they keep finding new ways to build audiences and sustainable news outlets, frequently going viral on digital platforms, and now producing podcasts and newsletters, too.

According to a report by the Journalists’ Union of Turkey, 26 journalists in Turkey were in jail as of May 3. More than 270 journalists were put on trial last year, 57 others were physically assaulted, and 54 news websites and 1,355 articles were blocked, while independent news outlets were forced to pay more than 10 million Turkish Liras as administrative fines over their reporting.

These numbers may soon rise because the press freedom situation in Turkey is likely to get worse before it gets better. Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian government can now target digital media even more aggressively with the disinformation law as his re-election campaign gathers steam. As Rappler cofounder and Nobel Peace Prize Winner Maria Ressa asked in her Nobel speech, “How can you have election integrity if you don’t have the integrity of facts?”

Emre Kizilkaya, a 2019 Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow, is the editor of journo.com.tr and the chair of International Press Institute’s (IPI) National Committee in Turkey.