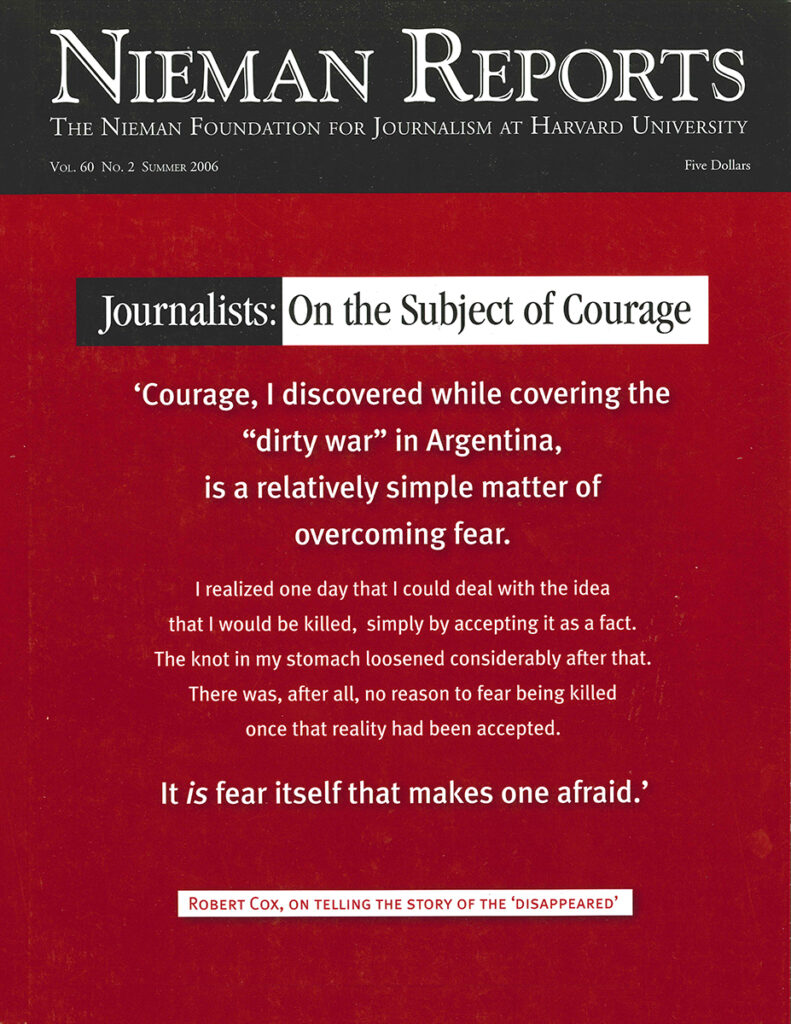

Journalists: On the Subject of Courage

Courage, as these journalists remind us, exposes itself in different guises. It can be found in the wisdom of understanding when danger finally has outweighed the risk. Or it can surface when threats to personal safety lurk but the lessons of training combine with inner strength to push fear aside and persevere. Courage can reside, too, in a journalist's isolation when editorial stands taken shake the foundation of friendship and sever long-held ties to one's community. In this issue, glimpses of such journalistic courage are offered.

I remember when my friend kept asking me if I was the one who made a two-hour phone call from her apartment in Manhattan to a small town in the Midwest. For a year and a half I denied it because it was the number of a doctor who diagnosed me as having posttraumatic stress disorder. I had stress, and trauma, and the syndrome, but what I lacked was the "post" part. When I go back to Colombia I know the risks will come back to me. When a person wants to ignore a weakness, he forgets it exists. In my mind, I erased the doctor, too, until my friend one day asked me for this doctor's brochure that she had given me to read.

This friend was also the person who picked me up in New York on the day in 2000 when I arrived there as a man without a country and after I'd walked up and down Manhattan and through Queens for almost 12 hours. The next day and for half of my third in the United States I slept on her couch after she fed me my first American-style meal. When I woke up, she and her husband asked me questions about what I'd been through, listened as I told them my story, and then gave me the brochure about a posttraumatic disorder institute that they had coincidentally received that day. When they did this, I tried to explain that I was not becoming a crazy homeless person but simply someone enjoying the feeling of walking around when nobody is going to rape you or shoot you down.

When I was on my own, I was really less in need of professional care; just being with friends seemed enough to help with the feelings I had. What was hard, though, was that I couldn't stop thinking about how defenseless Juliana was, a dear friend with whom I'd shared an apartment in Colombia, and how my mother and other family members were doing in Colombia. My whole world felt wounded during my first months in the United States: I could not sleep and, when I did, it seemed only to dream weird things. I never could stop the feeling of waiting for another possible attacker to come.

When I shared these feelings with a Colombian colleague, his diagnosis was immediate: "Paranoia," he declared. He claimed that he is also paranoid but told me he doesn't feel uncomfortable. He rids himself of the feeling by quoting firefighters who say "even false alarms save people." Not being paranoid, I think, can be a big mistake. For example, it might seem unlikely that a guy with crimson jeans and a yellow shirt would be a killer, but in my experience there was at least one who was. For this reason, I don't feel good when I see a guy dressed in bright colors.

For me, paranoia means having the awareness required to size up the issues with which we work. The Midwest doctor said he could cure me, but I wasn't sure that ridding myself of paranoia — which I felt was a fundamental tool of survival while working in my country on stories about corruption or reporting war news — was a good idea. I never called the doctor again. Instead I decided to play some sports so I would sleep better, study, enjoy the country, and feed my dreams.

I sent the brochure about posttraumatic stress disorder to Colombia for other journalists who might be in need of this information. It described how psychologists were trained to listen and advise journalists after they'd experienced traumatic situations. With Colombian journalists, such situations were very familiar. In 2000, the year I came to the United States, there had been a huge number of death threats, killings and a brutal kidnapping. I was fortunate to have had an opportunity to leave — and in May of that year I did — but not all journalists were as lucky. Some friends went to Spain; nearly all of the exiled journalists drank a lot, became poorer, and sunk into deep depressions. Many colleagues I chatted with during my first months out of the country seemed not to be themselves — less than what they'd been in Colombia, as I was feeling myself.

After the September 11th attacks, a friend of mine, an elementary school counselor who was responsible for 21 kids who were experiencing sleep problems, talking about death, and not feeling "normal," asked me for this brochure. Their school was one of the first evacuated in the wake of the attacks. She also needed care such as I'd received, but she felt that the children had problems that required a lot more treatment.

Journalists' Deaths

I had met my American friends when I went to Queens, New York to report on the killing in 1992 of a Latino journalist in the Little Colombia section. Manuel de Dios Unanue, the former editor of El Diario-La Prensa, the biggest U.S. Latino paper of his time, had been shot dead in a restaurant. He was a "crusader," according to The New York Times in its news coverage and editorials. The Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) suggested that his death was the result of racketeering activities that were a part of the city's Colombian community, where he lived for decades. In the summer of 1994, the Committee to Protect Journalists asked me to check on both of these versions from inside the neighborhood.

At the time of his death, Unanue was publishing a series of the Colombian mafia leaders' biographies and heavily criticizing the mafia's influence in the community's life. He was obsessed, too, with El Espectador, the Colombian newspaper that reported on drug trafficking, which had put more than 14 journalists on a list of those silenced by death and a car-bomb explosion that almost destroyed its entire plant in 1989. Unanue had gotten fired after publishing some editorials at El Diario-La Prensa that pushed against the mafia in the neighborhood and did so by naming names. The CJR reporter understood the complaint as extortion; but for most of Unanue's readers, it was clear that this Puerto Rican journalist wasn't one of the mafia.

At the time I worked for El Espectador and had become almost an expert on the topic of journalists being killed by the Colombian mafia. In mid-1986, when I got my first assignment to do a story on drug trafficking, three journalists covering this beat had been killed. By the end of the year, when the paper's managing director, Guillermo Cano, was shot down in front of the newspaper, there had been five deaths in that one year. I learned a lot helping U.S. reporters to do articles about how our country had the highest murder rate of any in the world, about shootings that were happening in the streets, and the hunting of spies and mercenaries in Colombia. These reporters found me because my closest coworkers had either been killed or had to flee. I'd become the obituary correspondent and the contact person for those who had to flee to the United States, which I've had to do two times.

The death that hurt me the most was Julio Daniel's. He was a terrific writer, a reporting partner of mine. He dared to do the series "What Violence Has Left" as he visited the places that were deserted after the 36 massacres I'd reported on in 1987 and 1988. He and I kidded each other and talked to each other constantly as we wondered aloud why we were doing this kind of work. Julio used to say that he'd decided to give his life for this story because he felt we could be killed even by a stray bullet. We had expressions we used with each other to rank the danger involved with each story we did: "You smell flowers," or "You're going out with the foot first," or "You lost your head on that," all of which were mafia metaphors. Julio wasn't killed in 1991 for being a journalist for El Espectador; he was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I've had some dreams with Julio's ghost and, eight years after he died, I think at last I felt some of what he felt. That moment happened when I walked out of the door at the military prison after I did my last interview for El Espectador. In a week I'd received 65 letters of hate and hundreds of hate-filled phone calls. My life was surrounded by guns, some of them for my protection. This moment will never be erased from my mind.

I went to the United States because of my friends. They convinced me that it would be a good place to "neutralize" the powerful interests about whom I'd written in my story. My article had focused on the time and place coincidences involving a colonel, who masterminded a 1997 massacre (he was the person in the military jail), and 12 members of a group of U.S. Army trainers. What was hard for me to explain to my Colombian friends was that if Americans were the subjects of the piece, why I would leave to go to America. For me, I understood that the United States doesn't work like my country. In fact, the journalist I admire most was an American, Gary Webb, another "kamikaze" or "crusader" whose investigation of CIA involvement with Colombian cocaine traffickers to support the Nicaragua war appeared as a lengthy series in the San Jose Mercury News. The government sued him; he was fired from the paper and, after being found not guilty by a jury, he committed suicide.

I remember the fears I had when I was reporting the massacre story. At the time, the U.S. Congress was discussing big military involvement in Colombia. But when I heard the personal testimony of people who lost family members in the Mapiripán massacre, I knew I had to tell this story. That's my duty.

In 2001, I was ready to go back to Colombia, even though many news organizations were closing down. To me, this meant there would be less risk for journalists; fewer journalists would equal, in my mind, fewer attacks. The feeling I had as I returned to my country was that with all that the war in Colombia had done to all of us, I was returning to live in a place where there was bound to be an epidemic of posttrauma disease.

Ignacio "Nacho" Gómez, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, is the investigations director at Red Independiente/Noticias Uno in Bogotá, Colombia.

This friend was also the person who picked me up in New York on the day in 2000 when I arrived there as a man without a country and after I'd walked up and down Manhattan and through Queens for almost 12 hours. The next day and for half of my third in the United States I slept on her couch after she fed me my first American-style meal. When I woke up, she and her husband asked me questions about what I'd been through, listened as I told them my story, and then gave me the brochure about a posttraumatic disorder institute that they had coincidentally received that day. When they did this, I tried to explain that I was not becoming a crazy homeless person but simply someone enjoying the feeling of walking around when nobody is going to rape you or shoot you down.

When I was on my own, I was really less in need of professional care; just being with friends seemed enough to help with the feelings I had. What was hard, though, was that I couldn't stop thinking about how defenseless Juliana was, a dear friend with whom I'd shared an apartment in Colombia, and how my mother and other family members were doing in Colombia. My whole world felt wounded during my first months in the United States: I could not sleep and, when I did, it seemed only to dream weird things. I never could stop the feeling of waiting for another possible attacker to come.

When I shared these feelings with a Colombian colleague, his diagnosis was immediate: "Paranoia," he declared. He claimed that he is also paranoid but told me he doesn't feel uncomfortable. He rids himself of the feeling by quoting firefighters who say "even false alarms save people." Not being paranoid, I think, can be a big mistake. For example, it might seem unlikely that a guy with crimson jeans and a yellow shirt would be a killer, but in my experience there was at least one who was. For this reason, I don't feel good when I see a guy dressed in bright colors.

For me, paranoia means having the awareness required to size up the issues with which we work. The Midwest doctor said he could cure me, but I wasn't sure that ridding myself of paranoia — which I felt was a fundamental tool of survival while working in my country on stories about corruption or reporting war news — was a good idea. I never called the doctor again. Instead I decided to play some sports so I would sleep better, study, enjoy the country, and feed my dreams.

I sent the brochure about posttraumatic stress disorder to Colombia for other journalists who might be in need of this information. It described how psychologists were trained to listen and advise journalists after they'd experienced traumatic situations. With Colombian journalists, such situations were very familiar. In 2000, the year I came to the United States, there had been a huge number of death threats, killings and a brutal kidnapping. I was fortunate to have had an opportunity to leave — and in May of that year I did — but not all journalists were as lucky. Some friends went to Spain; nearly all of the exiled journalists drank a lot, became poorer, and sunk into deep depressions. Many colleagues I chatted with during my first months out of the country seemed not to be themselves — less than what they'd been in Colombia, as I was feeling myself.

After the September 11th attacks, a friend of mine, an elementary school counselor who was responsible for 21 kids who were experiencing sleep problems, talking about death, and not feeling "normal," asked me for this brochure. Their school was one of the first evacuated in the wake of the attacks. She also needed care such as I'd received, but she felt that the children had problems that required a lot more treatment.

Journalists' Deaths

I had met my American friends when I went to Queens, New York to report on the killing in 1992 of a Latino journalist in the Little Colombia section. Manuel de Dios Unanue, the former editor of El Diario-La Prensa, the biggest U.S. Latino paper of his time, had been shot dead in a restaurant. He was a "crusader," according to The New York Times in its news coverage and editorials. The Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) suggested that his death was the result of racketeering activities that were a part of the city's Colombian community, where he lived for decades. In the summer of 1994, the Committee to Protect Journalists asked me to check on both of these versions from inside the neighborhood.

At the time of his death, Unanue was publishing a series of the Colombian mafia leaders' biographies and heavily criticizing the mafia's influence in the community's life. He was obsessed, too, with El Espectador, the Colombian newspaper that reported on drug trafficking, which had put more than 14 journalists on a list of those silenced by death and a car-bomb explosion that almost destroyed its entire plant in 1989. Unanue had gotten fired after publishing some editorials at El Diario-La Prensa that pushed against the mafia in the neighborhood and did so by naming names. The CJR reporter understood the complaint as extortion; but for most of Unanue's readers, it was clear that this Puerto Rican journalist wasn't one of the mafia.

At the time I worked for El Espectador and had become almost an expert on the topic of journalists being killed by the Colombian mafia. In mid-1986, when I got my first assignment to do a story on drug trafficking, three journalists covering this beat had been killed. By the end of the year, when the paper's managing director, Guillermo Cano, was shot down in front of the newspaper, there had been five deaths in that one year. I learned a lot helping U.S. reporters to do articles about how our country had the highest murder rate of any in the world, about shootings that were happening in the streets, and the hunting of spies and mercenaries in Colombia. These reporters found me because my closest coworkers had either been killed or had to flee. I'd become the obituary correspondent and the contact person for those who had to flee to the United States, which I've had to do two times.

The death that hurt me the most was Julio Daniel's. He was a terrific writer, a reporting partner of mine. He dared to do the series "What Violence Has Left" as he visited the places that were deserted after the 36 massacres I'd reported on in 1987 and 1988. He and I kidded each other and talked to each other constantly as we wondered aloud why we were doing this kind of work. Julio used to say that he'd decided to give his life for this story because he felt we could be killed even by a stray bullet. We had expressions we used with each other to rank the danger involved with each story we did: "You smell flowers," or "You're going out with the foot first," or "You lost your head on that," all of which were mafia metaphors. Julio wasn't killed in 1991 for being a journalist for El Espectador; he was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I've had some dreams with Julio's ghost and, eight years after he died, I think at last I felt some of what he felt. That moment happened when I walked out of the door at the military prison after I did my last interview for El Espectador. In a week I'd received 65 letters of hate and hundreds of hate-filled phone calls. My life was surrounded by guns, some of them for my protection. This moment will never be erased from my mind.

I went to the United States because of my friends. They convinced me that it would be a good place to "neutralize" the powerful interests about whom I'd written in my story. My article had focused on the time and place coincidences involving a colonel, who masterminded a 1997 massacre (he was the person in the military jail), and 12 members of a group of U.S. Army trainers. What was hard for me to explain to my Colombian friends was that if Americans were the subjects of the piece, why I would leave to go to America. For me, I understood that the United States doesn't work like my country. In fact, the journalist I admire most was an American, Gary Webb, another "kamikaze" or "crusader" whose investigation of CIA involvement with Colombian cocaine traffickers to support the Nicaragua war appeared as a lengthy series in the San Jose Mercury News. The government sued him; he was fired from the paper and, after being found not guilty by a jury, he committed suicide.

I remember the fears I had when I was reporting the massacre story. At the time, the U.S. Congress was discussing big military involvement in Colombia. But when I heard the personal testimony of people who lost family members in the Mapiripán massacre, I knew I had to tell this story. That's my duty.

In 2001, I was ready to go back to Colombia, even though many news organizations were closing down. To me, this meant there would be less risk for journalists; fewer journalists would equal, in my mind, fewer attacks. The feeling I had as I returned to my country was that with all that the war in Colombia had done to all of us, I was returning to live in a place where there was bound to be an epidemic of posttrauma disease.

Ignacio "Nacho" Gómez, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, is the investigations director at Red Independiente/Noticias Uno in Bogotá, Colombia.