In December 2020, before the rollout of the Covid-19 vaccine, when many had chosen to celebrate Thanksgiving in groups, which sent Covid cases soaring, The New York Times ran an opinion piece on why we should not shame people who traveled during the holidays. That these individualistic choices were burdening already overtaxed healthcare workers and causing people to die of preventable illnesses because they simply could not access care didn’t merit a mention in the piece.

This idea that we should not shame people for ignoring Covid recommendations — even when it was costing lives — became pervasive. So much so that in an early 2021 article I wrote for Slate about the social benefits of shame, I noted that, “regardless of how abhorrent a person’s behavior is, apparently the worst thing you can do is shame them for it.”

What was less obvious to me at the time, but has become clearer in the intervening years, is that many in the press did not, in fact, oppose all uses of shame. The same news outlets that were saying with one breath not to shame people who bucked Covid restrictions were with another shaming those who continued to be concerned about Covid once vaccines emerged. One example: “Very liberal Americans remain more worried about the virus than almost any other demographic group, including the elderly,” wrote David Leonhardt in an August 2022 column. “That pattern does not seem consistent with scientific reality, given that the very liberal are younger than any other ideological group and that Covid’s effects are far worse for older people.”

Bias is baked into Leonhardt’s analysis. By focusing on one metric — age — he skips past others, such as the fact that liberals tend to be more diverse and people of color are more likely to live in multigenerational households, where a young person risks not only infecting themselves with Covid but also spreading it to a parent or a grandparent. Nationwide, more than 200,000 children have lost a parent or caregiver to Covid, with teens and people of color most represented. None of those factors show up in Leonhardt’s reasoning about why a youthful demographic might be concerned about Covid.

“There’s a hyper focus on deaths, on hospital capacity systems, which is important but public health isn’t just about whether you’ve got morgue trucks on your block,” says Lucky Tran, the director of science communication and media relations at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “It’s about the overall health of the population over time. Getting chronic illness, even getting an acute illness and losing a week or two of wages, that’s a big deal for a lot of people, and it’s something that we should address if we care at all about equity and fairness in society.”

The New York Times is not alone. Outlets like The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and NPR, to name just a few, have amplified voices and arguments that helped create a narrative that not only pathologizes those who remain cautious about the disease, but also fails to adequately convey the risks associated with Covid such that many people are unwittingly taking on potentially lifelong risks.

In the process, we’ve failed at our field’s core tenets — to hold power to account and to follow the evidence. Our failures here could last a generation. As reporters, it’s our responsibility to accurately represent the needs of diverse perspectives and avoid an ableist bias that diminishes the real and lasting health concerns not only of those who are keenly at risk but those who are cautious about repeatedly catching a virus that scientists are still grappling to understand.

To understand why, it helps to understand some things about Covid — especially relative to the media’s favorite point of comparison: the flu.

First, the flu has a seasonality to it — beginning to rise in October and ebbing come April. Covid has no such predictability. Delta was identified in the U.S. in March 2021 and was the dominate strain by June. The first American case of Omicron was identified in late November. Further, Covid antibodies — even from infection — decline rapidly. But antibodies to the flu can linger for decades (which is not to say skip your flu shot, since the vaccines protect against different strains). And finally, even now after the advent of vaccines, more than 1,500 people are still dying each week from Covid. Overall, based on data from Johns Hopkins and the CDC, Covid killed roughly four times more people than the flu did during the last flu season. It remains a leading cause of death in the United States.

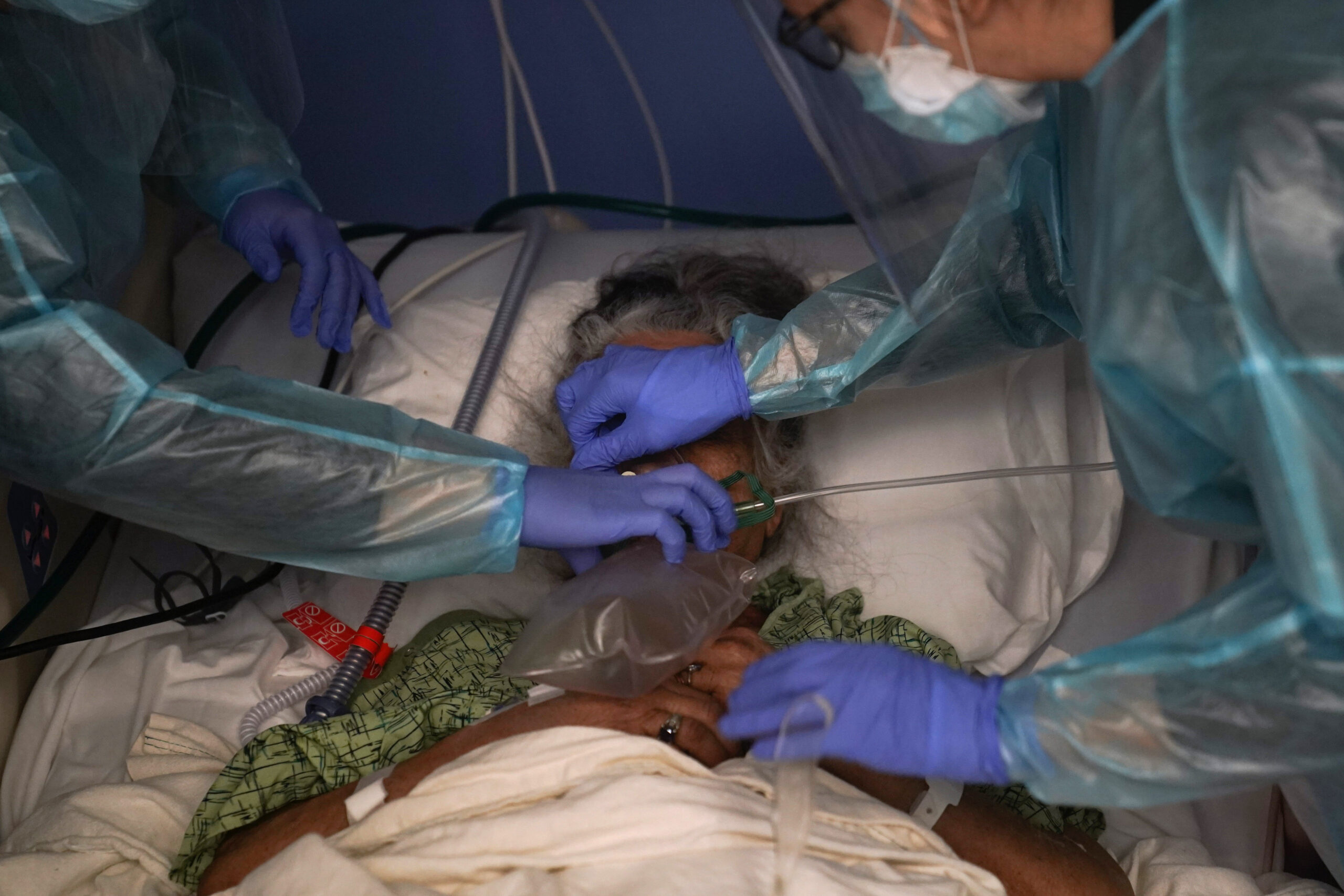

Bryan Olin Dozier/NurPhoto via AP

Each Covid infection increases the risk of developing chronic health issues like diabetes — including in children — organ failure, stroke, heart conditions, kidney disease, and mental health problems. These are just the problems we know about. We know from other viruses, like polio, that some of the consequences can take years to appear. Post-polio syndrome, which is thought to stem from a deterioration of nerve cells, can take as long as 40 years to show up.

Additionally, there’s the risk of long Covid or clusters of health issues that can last months or even years after initial infection. These range from exhaustion so severe that people with the condition find it difficult to work or socialize to heart palpitations, difficulty thinking and retaining information to severe anaphylactic reactions in the absence of an allergic trigger.

And yet in a January 2022 appearance on The Daily, Leonhardt argued that taking preventative measures like wearing masks is ideologically driven and downplays the risk of long Covid. “The science says vaccines are very effective at preventing serious Covid illness,” he said. “So, if you believe the science, it doesn’t argue only for getting vaccinated. It also argues for living your life in a way that reflects that you’ve been vaccinated.” (Eight months earlier, Leonhardt wrote, “The pandemic is in retreat. In the United States, there is now an excellent chance that the retreat is permanent.”)

What this looks like in practice is a very individualistic approach to public health. If you are at low risk, live your life with only a minimal consideration for those you might be putting at risk. Sure, put on a mask when visiting your grandparents, but don’t worry about someone else’s grandparent when you ride transit without a mask. It’s a perspective that fails to consider the needs of anyone who is perhaps older or who has comorbidities.

“People were testing regularly at their workplaces, in schools and complying with that,” Eiryn Griest Schwartzman, executive director of COVID Safe Campus, a coalition of academics and advocates pushing for improved mitigation efforts and disability inclusion in higher education, told me. “And then suddenly, the narrative shifted where that became something that’s ‘unfavorable’ even though polls still show that masking and other precautions like that are still popular and understood in shared public spaces, like transit and healthcare. There’s still public support, but it’s not being reported on in that way. More often it’s being reported on as something that support is fading, or unfeasible or not politically viable when it absolutely is. But those narratives are self-perpetuating, and they feed into policy.”

There are many ways to improve coverage of Covid. More stories need to include voices and perspectives of people from communities that are most at risk from an infection, such as people from the disabled community, from low-income communities, people of color, and elderly people. And their perspectives should be included broadly — not just in stories specifically about their communities. We also need to take a step back and look at who we are including. Tran notes that the media relies heavily on quoting medical doctors, for example, who are often not trained in public health.

“There have been some sources who have been consistently wrong about making predictions about the pandemic, like saying the pandemic is over, we had herd immunity, that Covid didn’t spread into places like schools,” said Tran. “They’ve been on the record, saying these wrong things, but then they keep popping up in the media, and being quoted and taken as authoritative sources afterwards. There hasn’t been adequate fact checking or balances within journalistic institutions. And I’m talking about mainstream institutions — top tier institutions.” Take, for example, people like Emily Oster, an economist who courted controversy for pushing to open schools at the height of the pandemic based on the claim that the risk of Covid spreading in schools was low. Later studies poked holes in her argument.

Last year, on Good Morning America, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said this about a study that showed Covid deaths among people who received the primary vaccination series were about .003 percent: “The overwhelming number of deaths, over 75 percent, occurred in people who had at least four comorbidities. So really these are people who were unwell to begin with — and yes, really encouraging news in the context of Omicron.”The news host did not push back on her characterization. But her comments elicited the concern of many people with disabilities who argued it seemed like the director of the CDC was saying that it’s fine if sick people die of Covid. Walensky’s “really encouraging news” — a framing for which she later apologized — also seemed to ignore that nationwide around a quarter of adults have multiple comorbidities.

A lot of people are still at risk of dying from Covid, and many of us share households with them. And, of course, if one gets Covid and develops long Covid, they might become disabled and thus disposable under the same narrative that helped sicken them in the first place.

That the statement went unchallenged is, in part, likely because it’s a phrase we repeat routinely — and the media reinforces it: It’s mostly the elderly and disabled people who die of Covid. It’s a phrase that, whether we mean to or not, treats certain categories of people — the other — as less deserving of life. And yet even the most narcissistic among us should recognize that eventually, if we’re lucky, we get old. Or that we are all one twist of fate, one choice, one quirk of genetics away from disability.

This bias is “largely driven by systemic ableism,” says Griest Schwartzman, who has mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), both of which are some of the more common manifestations of long Covid. “Those in power are being prioritized over communities at large. And it’s those people that have the most privilege to protect themselves that are less affected, because they have workplaces and schools with incredible ventilation, many of them still work from home or have cars or have housing that isn’t congregate-like living, not in an apartment, having no common spaces where you live. So they’re sheltered from it.”

This push for “normal” emerged quickly. “Yes, it’s going to be a hot vax summer,” reads one CNBC headline from May 2021. This was weeks before many adults had even received their first dose of the vaccines, months before a vaccine would be available for older teens, and more than a year before the FDA would authorize vaccines for young children.

More recently, in The New Yorker, Emma Green profiled the People’s CDC, a loose coalition that thinks Covid-19 health policies should factor in the wellbeing of the whole community, including the elderly, immunocompromised, and the disabled. Green asked if they were communists and downplayed the risks of long Covid. “The People’s C.D.C. talks about ‘science’ as proof that the members’ position is correct, when in reality they’re making a case for how they wish the world to be, and selecting scientific evidence to build their narrative,” Green wrote. “It’s a kind of moralistic scientism — a belief that science infallibly validates lefty moral sensibilities.”

In January, Time Magazine chose to amplify the voice of Dr. Stephen Phillips, an epidemiologist who wrote, “After three years of the imposition, followed by gradual easing, of lockdowns, quarantine, isolation, testing, vaccination and masking, how does the holdout one-third of the country move from the current obsolete but ingrained ‘avoid exposure’ paradigm to an endemic ‘accept exposure’ reality? This not only has significant medical, public and mental health implications; it will also accelerate a return to a fully-functioning and dynamic society.” There was little mention of long Covid in the piece, even though Phillips had written for the niche audience of the New England Journal of Medicine, arguing that “current numbers and trends indicate that ‘long-haul Covid’ (or ‘long Covid’) is our next public health disaster in the making.”

“I think people overplay this idea that the cost is too much to take any precautions,” says Tran.

Brittainy Newman/AP Photo, File

Once the vaccines were out and Covid restriction began easing, news and opinion pieces seemed to validate the changes even with every new surge. “Yes, more variants may emerge in the future. That’s why we should lift restrictions now,” published The Washington Post in February 2022 just as the first Omicron wave was receding. “So while the much-hyped ‘hot vax summer’ of 2021 famously did not materialize, thanks to the delta variant, maybe this time we can enjoy a ‘hot vax spring,’” wrote Leana Wen, an emergency physician, professor of health policy and management, former health commissioner for Baltimore, and contributing columnist for The Post. “New and possibly dangerous variants are likely to emerge. But it is precisely because of this future threat that we need to allow normalcy now.” But by late spring, Covid cases were soaring again. Wen has been roundly criticized for this and other pieces — in one she suggested that too many deaths were being attributed to Covid, a thesis unsupported by data — by public health workers and experts, who have said she “has promoted unscientific, unsafe, ableist, fatphobic, and unethical practices during the COVID-19 pandemic,” says a petition signed by more than 600 in the field.

But those pieces were incongruent both with public sentiment — and the science as it evolves to show us the growing lists of health problems associated with Covid.

“There’s a CDC study which shows that many people are willing to take precautions, like being vaccinated and wearing masks if they know that Covid levels are high,” says Tran. “The problem is that the majority of people are not aware that Covid levels are consistently high … because of the narratives coming through the media.”

Journalists report that Covid numbers are dropping but fail to put the decline in the proper context, adds Tran. “The cases are dropping from extremely high to very high. We still have a high baseline of Covid throughout the year, basically,” he says.

It’s our responsibility as journalists to convey that nuance.

More and more of us are living in ways that make it easier for Covid to spread and harder to track. Many of the adaptations, such as online schooling, that would let higher risk people remain participants in society have been tossed out. The CDC shifted its Covid tracking from community transmission to community levels, which is more opaque for people not in the field. Community transmission tells you how much Covid is spreading. Community levels is a hybrid measure that mixes transmission levels with hospitalization levels and can show community spread as low even when community transmission is increasing.Meanwhile, Johns Hopkins dropped its Covid tracker altogether. Mask requirements have vanished from schools, many of which have also rolled back testing. Restaurants have ripped out their outdoor dining setups. Cities have removed masking requirements on mass transit, and the CDC has eased its recommendations on masking in hospitals and other healthcare settings.

And with the Biden administration lifting the Covid public health emergency, testing, vaccinations, and Covid treatments are all poised to get more expensive. The government pays a discounted rate of $530 for a course of the anti-viral Paxlovid. That cost is expected to rise significantly for individuals. Pfizer says its Covid-19 vaccine will cost between $110-$130.

All of this is to say, these facts are important context that belongs in coverage of the risk posed by Covid. Isn’t our role as journalists to give people the full story and allow people to make fully informed decisions?

Yes, there are individual stories that touch on these other risks, such as a February CBS News story on the links between Covid and diabetes, but not enough — and much of the information coming from major, trusted news organizations often serves to minimize the risks. Even news stories about Covid that show promise or hope in combating the disease should highlight the growing list of long-term health impacts of the virus and the fact that many are still unknown. We should note that the risks go up with repeated infection and that it’s rational for even the healthiest among us to try to take reasonable measures to avoid getting Covid.

We also need to be vigilant around our unconscious biases that frame some lives as worth saving while others are not.

And that’s not the only way in which biases can creep in.

At a time when the CDC estimates that nearly a quarter of adults who have had Covid have also experienced long Covid symptoms, when research is showing a rise in the number of heart attacks across all age groups — but most especially among 25- to 44-year-olds — when researchers are finding evidence that Covid overwhelms the immune system to the point where it may not be able to protect against certain cancers as well, the narrative that many in the media are pushing — that infections don’t matter and it’s time to move on — will cost lives.

“We know that people are more likely to wear masks if they understand how high the risk is. Or if they understand that it’s airborne and not droplets, so like six feet apart isn’t enough, and we actually need to keep masks on because it lingers in the air,” says Griest Schwartzman. “But a lot of people still don’t know that, or they’ve been made to believe that maybe it wasn’t that serious, or they don’t have a clear understanding and don’t know people that could clarify that for them. It really harms people that don’t have access to the health literacy they need to understand themselves how at risk they are,” they added. “And that’s not their fault. It’s the fault of a lack of accurate health and science communication.”

It’s also the fault of the media.