The Search for True North: New Directions in a New Territory

In this time of accelerating change, how journalists do their work and what elements of journalism will survive this digital transformation loom as questions and concerns. By heading in new directions and exploring the potential to be found in this new territory of interactivity and social media, journalists – and others contributing to the flood of information – will be resetting the compass bearing of what constitutes “true north” for journalism in our time.

Our presidential election was indeed historic, but not just for the reasons emblazoned in headlines throughout the world. It was also the most closely monitored election in U.S. history, as everyone from CNN to The Huffington Post to Harvard University asked people to document their voting experience and provide instant reports on problems at the polls. Thousands responded, sending in text messages, photographs, videos and even voice mails. The resulting data were aggregated and displayed—in real time—on maps, in charts, and over RSS feeds.

All of this activity signaled a small but significant advance in the use of crowdsourcing as a new tool in digital journalism. While crowdsourcing, or citizen journalism, has been widely embraced by all manner of news operations over the past several years, its track record has been decidedly spotty. In theory, crowdsourcing offers outlets like newspapers and newscasts and Web sites an opportunity to improve their reporting, bind their audiences closer to their brands, and reduce newsroom overhead. In reality, relying on readers to produce news content has proved to be a nettlesome—and costly—practice.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Howe’s article, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing” »I coined the word “crowdsourcing” in a Wired magazine article published in June 2006, though at that time I didn’t focus on its use in journalism. It was—and is—defined as the act of taking a job once performed by employees and outsourcing it to a large, undefined group of people via an open call, generally over the Internet. Back then I explored the ways TV networks, photo agencies, and corporate R&D departments were harnessing the efforts of amateurs. I had wanted to include journalism in the piece, but there was a dearth of examples.

That quickly changed. Not long after Wired published this article the term began to seep into the pop cultural lexicon, and news organizations started to experiment with reader-generated content. Around this time, some of the more memorable moments in journalism had been brought to us not by a handful of intrepid reporters, but by a legion of amateur photographers, bloggers and videographers. When a massive tsunami swept across the resort beaches of Thailand and Indonesia, those “amateurs” who were witness to it sent words and images by any means they could. When homegrown terrorists set off a series of bombs on buses and subways in London, those at the scene used their cell phone cameras to transmit horrifying images. Hurricane Katrina reinforced this trend: As water rose and then receded, journalists—to say nothing of the victims’ families—relied on information and images supplied by those whose journalistic accreditation started and ended with the accident of their geographical location.

With these events, the news media’s primary contribution was to provide the dependable Web forum on which people gathered to distribute information. By late 2006, the stage seemed set for the entrance of “citizen journalism,” in which inspired and thoughtful amateurs would provide a palliative for the perceived abuses of the so-called mainstream media. These were heady times, and a spirit of optimism—what can’t the crowd do?—seemed to pervade newsrooms as well as the culture at large.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Howe’s July 2007 story in Wired, entitled “To Save Themselves, US Newspapers Put Readers to Work” »At Wired, we were no less susceptible to the zeitgeist. In January 2007, we teamed up with Jay Rosen’s NewAssignment.Net to launch Assignment Zero. We anticipated gathering hundreds of Web-connected volunteers to discuss, report and eventually write 80 feature articles about a specified topic. At about the same time, Gannett was re-engineering its newsrooms with the ambition of putting readers at the center of its new business strategy. I had a close-up view of both efforts. At Assignment Zero, I was trying to help apply the crowdsourcing principles, while in 2006 I broke the news of Gannett’s retooling—the most significant change since it launched USA Today in 1982—after spending several months reporting on the sea change at the company for Wired Magazine and for my book, “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business.”

EDITOR'S NOTE

Read "Creating a New Platform to Support Reporting," by David Cohn, an Assignment Zero alumnus »It would be easy to say that the original optimism was simply naiveté, but that wouldn’t be exactly correct. As it turns out, there’s a lot that the crowd can’t do or, at least, isn’t interested in doing. Recently I spent time talking to sources at Gannett as well as some of my Assignment Zero alumni to revisit what went right, what didn’t, and to pull from them valuable lessons for others to put to good use. What I’ve learned has reinforced my belief that crowdsourcing has limited applicability to journalism—it’s a spice, not a main ingredient in our fourth estate. I’ve also come to fear that news organizations will rely more and more on reader-generated content at the expense of traditional journalism. But what’s also clear is that the animating idea—our readers know more than we do—is evolving into something that, if used wisely, will be far more efficient and useful than our first, early attempts at this new form of journalism. At any rate, crowdsourcing isn’t going away, so it behooves all of us to make sure it improves journalism but does not replace it.

Assignment Zero’s Formula

Assignment Zero was intended to demonstrate, as I wrote in a Wired.com piece on the occasion of the project’s launch in March 2007, that “… a team of professionals, working with scores of citizen journalists, is capable of completing an investigative project of far greater scope than a team of two or three professionals ever could.” In this case, the first topic of investigation by the crowd would be “… the crowd itself—its wisdom, creativity, power and potential.” Dozens of “subject pages” were constructed, ranging from open source car design to architecture. Included was even a subject file called “the crowdsourced novel.” Within each topic, there were up to 10 assignments, in which contributors could report, brainstorm or “write the feature.” It was an ideal format for a newsroom. But then, we weren’t soliciting journalists.

We came out of the gate strong. The New York Times published a column devoted to Assignment Zero, and the effort received lots of positive attention from the blogosphere. Within the first week, hundreds of volunteers had signed up. But just as quickly, these enthusiastic volunteers drifted away. Six weeks later, most of our topic pages were ghost towns.

What had we done wrong? Here’s a few lessons learned:

Six weeks in, we turned things around. We scrapped most of the feature stories; instead people were asked to conduct Q&As. Critically, we shifted our tone. Instead of dictating assignments to people, we let the crowd select whom they wanted to interview or suggest new subjects entirely. In the end, about 80 interviews made it to the Web site as published pieces, and the majority were insightful and provocative. What their interviews made clear is these volunteer contributors tackled topics about which they were passionate and knowledgeable, giving their content a considerable advantage over that of professional journalists, who often must conduct interviews on short notice, without time for preparation or passion for the subject.

Gannett’s Newsroom Reinvention

Gannett, too, found itself experimenting with crowdsourcing in some of its newsrooms but did so for different reasons and in different ways than Assignment Zero. Conceived as a wholesale reinvention of the newsroom—rechristened the “information center”—Gannett’s readers were now to reside at the heart of the two planks in its strategy.

RELATED ARTICLE

Betty Wells, special projects editor at The News-Press, wrote about the newspaper’s use of crowdsourcing for the Spring 2008 issue of Nieman Reports in an article entitled, “Using Expertise From Outside the Newsroom.”After a successful initial foray into crowdsourced reporting—at The (Fort Myers) News-Press, in which a citizen-engaged investigation unearthed corruption in a sewage utility in a town in Florida—Gannett decided to export this model to its other newspapers. Readers (a.k.a. community members) would also play a significant newsroom role in the renamed “community desk,” which would oversee everything from blogs to news articles written by readers.

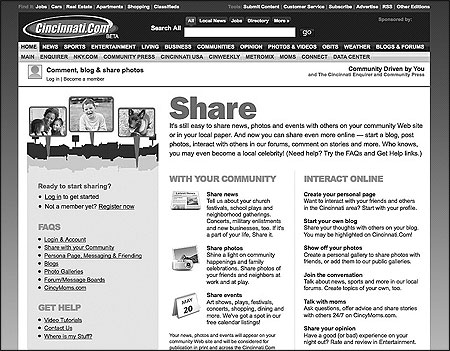

In reporting on Gannett’s strategy, I chose to focus on how the changes were being implemented at one paper, The Cincinnati Enquirer. One indication of how the newsroom was changing was the shift in job responsibilities. A longtime metro reporter, Linda Parker, had recently been reassigned as “online communities editor.” Every Enquirer Web page prominently featured the words “Get Published” as a way of eliciting stories, comments and anything else Cincinnatians might feel compelled to submit. It all landed in Parker’s queue; perhaps not surprisingly, these words and videos never have resembled anything commonly considered journalism.

Even figuring out how best to prompt contributors has revealed valuable lessons to those at the Enquirer—ones that other news organizations can learn from. “It used to read, ‘Be a Citizen Journalist,’” Parker told me. “And no one ever clicked on it. Then we said, ‘Tell Us Your Story,’ and still nothing. For some reason, ‘Get Published’ were the magic words.”

Now, nearly two years into the experiment, the Enquirer considers this feature to be an unequivocal success. I sat with Parker, a cheerful woman in her mid-50’s, in April of last year as she pored over several dozen submissions she had received that day. There was one written by a local custom car builder trumpeting his upcoming appearance on a BET show, and another, expressing with the intensity of emotional passion befitting the circumstance, is a notice for a play being held to raise funds for a fifth-grader’s bone marrow transplant. Parker almost never rejects anything she receives, though she scans each one for “the F-word,” and then posts it to the site. “A few years ago these would have come across the transom as press releases and been ignored,” she says.

This observation points to a central problem with Gannett’s strategy—indeed, with both the hyperlocal and crowdsourcing movements in general. Readers are content to leave the gritty aspects of reporting to journalists; they prefer to focus on content and storytelling that Nicholas Lemann, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, once characterized in The New Yorker as being the equivalent of the contents of a church newsletter.

As it turns out, Tom Callinan, the Enquirer’s editor, observed a while into the project “even ‘Get Published’ was too newspaperlike in its sound. People don’t want to get published. They want to ‘share.’” And so this is what the Web site’s button now encourages its readers to do. The results continue, as Callinan says, to tend toward “pretty fluffy stuff.”

Lessons Learned

So what are we to take away from these experiments? Readers are very interested in playing a role in the creation of their local media. They don’t necessarily want to write the news; what they want is to engage in a conversation. This doesn’t mean, however, that they don’t have valuable contributions to make. This fall, Callinan told me, readers shared with others on the Enquirer Web site news about a stabbing at a local strip club and a photograph of a theater fire. “We were able to confirm the stabbing,” he said. “We would have never known about it without the tip.” It might not be grist for a Pulitzer, but it fills the copy hole.

Nor were these key lessons lost on those of us involved in Assignment Zero. In fact, Assignment Zero’s community manager, Amanda Michel, employed the lessons of what didn’t work adeptly at her next venture, directing The Huffington Post’s effort, Off the Bus, with its citizen-generated coverage of the presidential campaign. Rather than duplicate what journalists were doing, Off the Bus leveraged its strength—namely, the size of its network of 12,000 “reporters.” With citizen correspondents spread across the nation and ready to attend smaller rallies, fundraisers and get-out-the-vote events that the national press ignored, Off the Bus found its niche.

Off the Bus became arguably the first truly successful example of crowdsourced journalism with some of its citizen reporters breaking national stories. Perhaps its most significant story was about the moment when Barack Obama, at a nonpress event fundraiser in San Francisco, made his famous comment about how rural Americans “cling to guns or religion” as an expression of their frustration. However, this reporting by Mayhill Fowler, the citizen journalist who broke this story, actually drew attention away from Off the Bus’s broader achievement. Toward the end of the campaign, Off the Bus was publishing some 50 stories a day, and Michel—with the help of her crowd—was able to write profiles of every superdelegate, perform investigations into dubious financial contributions to the campaigns, and publish compelling firsthand reports from the frontlines in the battleground states. The national press took note—and sent its kudos—but more importantly, readers noticed. Off the Bus drew 3.5 million unique visitors to its site in the month of September.

Michel achieved this because she took away valuable information from the failures of the experimentation at Assignment Zero. Rather than dictate to her contributors, she forged a new kind of journalism based on playing to their strengths. The result: Some contributors wrote op-eds, while others provided reporting that journalists at the Web site then used in weaving together investigative features, including one that explored an increase in the prescribing of hypertension medicine to African-American women during the campaign. They also contributed “distributed reporting,” in which the network of contributors performed tasks such as analyzing how local affiliates summed up the vice presidential debate. “We received reports from more than 100 media markets,” Michel said. “We really got to see how the debate was perceived in different regions.”

Is Off the Bus the future of journalism? Hardly, Michel contends, and I agree wholeheartedly. She regards Off the Bus as complimentary, not competitive, with the work done by traditional news organizations. “We didn’t want to be the AP. We think the AP does a good job. The question was what information and perspective can citizens, not reporters on the trail, offer to the public?” Nor does she claim the Off the Bus method would work with all stories. It’s easy to build such a massive network of volunteer reporters when the story is so compelling. But what happens when the topic generates far less passion, even if it is no less important—say, for example, the nutritional content in public school lunches?

The take-away message for journalists should be this: Adapt to these changes and do so quickly. “The future of content is conversation,” says Michael Maness, the Gannett executive who helped craft the company’s recent newsroom overhaul. Worth noting is that one of Gannett’s unqualified successes are the so-called “mom sites,” launched in some 80 markets. Each is overseen and operated online by a single journalist with the assignment of facilitating conversation while also providing information. “We’re moving away from mass media and moving to mass experience,” says Maness. “How we do that? We don’t know.”

Jeff Howe writes for Wired magazine and is the author of “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business,” published by Crown Business in 2008.

All of this activity signaled a small but significant advance in the use of crowdsourcing as a new tool in digital journalism. While crowdsourcing, or citizen journalism, has been widely embraced by all manner of news operations over the past several years, its track record has been decidedly spotty. In theory, crowdsourcing offers outlets like newspapers and newscasts and Web sites an opportunity to improve their reporting, bind their audiences closer to their brands, and reduce newsroom overhead. In reality, relying on readers to produce news content has proved to be a nettlesome—and costly—practice.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Howe’s article, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing” »I coined the word “crowdsourcing” in a Wired magazine article published in June 2006, though at that time I didn’t focus on its use in journalism. It was—and is—defined as the act of taking a job once performed by employees and outsourcing it to a large, undefined group of people via an open call, generally over the Internet. Back then I explored the ways TV networks, photo agencies, and corporate R&D departments were harnessing the efforts of amateurs. I had wanted to include journalism in the piece, but there was a dearth of examples.

That quickly changed. Not long after Wired published this article the term began to seep into the pop cultural lexicon, and news organizations started to experiment with reader-generated content. Around this time, some of the more memorable moments in journalism had been brought to us not by a handful of intrepid reporters, but by a legion of amateur photographers, bloggers and videographers. When a massive tsunami swept across the resort beaches of Thailand and Indonesia, those “amateurs” who were witness to it sent words and images by any means they could. When homegrown terrorists set off a series of bombs on buses and subways in London, those at the scene used their cell phone cameras to transmit horrifying images. Hurricane Katrina reinforced this trend: As water rose and then receded, journalists—to say nothing of the victims’ families—relied on information and images supplied by those whose journalistic accreditation started and ended with the accident of their geographical location.

With these events, the news media’s primary contribution was to provide the dependable Web forum on which people gathered to distribute information. By late 2006, the stage seemed set for the entrance of “citizen journalism,” in which inspired and thoughtful amateurs would provide a palliative for the perceived abuses of the so-called mainstream media. These were heady times, and a spirit of optimism—what can’t the crowd do?—seemed to pervade newsrooms as well as the culture at large.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Howe’s July 2007 story in Wired, entitled “To Save Themselves, US Newspapers Put Readers to Work” »At Wired, we were no less susceptible to the zeitgeist. In January 2007, we teamed up with Jay Rosen’s NewAssignment.Net to launch Assignment Zero. We anticipated gathering hundreds of Web-connected volunteers to discuss, report and eventually write 80 feature articles about a specified topic. At about the same time, Gannett was re-engineering its newsrooms with the ambition of putting readers at the center of its new business strategy. I had a close-up view of both efforts. At Assignment Zero, I was trying to help apply the crowdsourcing principles, while in 2006 I broke the news of Gannett’s retooling—the most significant change since it launched USA Today in 1982—after spending several months reporting on the sea change at the company for Wired Magazine and for my book, “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business.”

EDITOR'S NOTE

Read "Creating a New Platform to Support Reporting," by David Cohn, an Assignment Zero alumnus »It would be easy to say that the original optimism was simply naiveté, but that wouldn’t be exactly correct. As it turns out, there’s a lot that the crowd can’t do or, at least, isn’t interested in doing. Recently I spent time talking to sources at Gannett as well as some of my Assignment Zero alumni to revisit what went right, what didn’t, and to pull from them valuable lessons for others to put to good use. What I’ve learned has reinforced my belief that crowdsourcing has limited applicability to journalism—it’s a spice, not a main ingredient in our fourth estate. I’ve also come to fear that news organizations will rely more and more on reader-generated content at the expense of traditional journalism. But what’s also clear is that the animating idea—our readers know more than we do—is evolving into something that, if used wisely, will be far more efficient and useful than our first, early attempts at this new form of journalism. At any rate, crowdsourcing isn’t going away, so it behooves all of us to make sure it improves journalism but does not replace it.

Assignment Zero’s Formula

Assignment Zero was intended to demonstrate, as I wrote in a Wired.com piece on the occasion of the project’s launch in March 2007, that “… a team of professionals, working with scores of citizen journalists, is capable of completing an investigative project of far greater scope than a team of two or three professionals ever could.” In this case, the first topic of investigation by the crowd would be “… the crowd itself—its wisdom, creativity, power and potential.” Dozens of “subject pages” were constructed, ranging from open source car design to architecture. Included was even a subject file called “the crowdsourced novel.” Within each topic, there were up to 10 assignments, in which contributors could report, brainstorm or “write the feature.” It was an ideal format for a newsroom. But then, we weren’t soliciting journalists.

We came out of the gate strong. The New York Times published a column devoted to Assignment Zero, and the effort received lots of positive attention from the blogosphere. Within the first week, hundreds of volunteers had signed up. But just as quickly, these enthusiastic volunteers drifted away. Six weeks later, most of our topic pages were ghost towns.

What had we done wrong? Here’s a few lessons learned:

- Using the crowd to study crowdsourcing proved far too wonky and bewildering for most of our would-be citizen journalists.

- We failed to anticipate that while building a community can be difficult, maintaining it is much harder. We didn’t have a tier of organizers ready to answer questions and guide people in the right direction. With their earnest e-mails unanswered, quite naturally most volunteers drifted away.

- We expected the crowd would fall all over themselves for the opportunity to produce all the artifacts of the journalistic practice—reporter’s notes, inverted pyramid articles, and long-form features. It turned out that asking people to write a feature proved about as appealing as asking them to rewrite their college thesis. And so our contributors spoke with their feet.

Six weeks in, we turned things around. We scrapped most of the feature stories; instead people were asked to conduct Q&As. Critically, we shifted our tone. Instead of dictating assignments to people, we let the crowd select whom they wanted to interview or suggest new subjects entirely. In the end, about 80 interviews made it to the Web site as published pieces, and the majority were insightful and provocative. What their interviews made clear is these volunteer contributors tackled topics about which they were passionate and knowledgeable, giving their content a considerable advantage over that of professional journalists, who often must conduct interviews on short notice, without time for preparation or passion for the subject.

Gannett’s Newsroom Reinvention

Gannett, too, found itself experimenting with crowdsourcing in some of its newsrooms but did so for different reasons and in different ways than Assignment Zero. Conceived as a wholesale reinvention of the newsroom—rechristened the “information center”—Gannett’s readers were now to reside at the heart of the two planks in its strategy.

RELATED ARTICLE

Betty Wells, special projects editor at The News-Press, wrote about the newspaper’s use of crowdsourcing for the Spring 2008 issue of Nieman Reports in an article entitled, “Using Expertise From Outside the Newsroom.”After a successful initial foray into crowdsourced reporting—at The (Fort Myers) News-Press, in which a citizen-engaged investigation unearthed corruption in a sewage utility in a town in Florida—Gannett decided to export this model to its other newspapers. Readers (a.k.a. community members) would also play a significant newsroom role in the renamed “community desk,” which would oversee everything from blogs to news articles written by readers.

In reporting on Gannett’s strategy, I chose to focus on how the changes were being implemented at one paper, The Cincinnati Enquirer. One indication of how the newsroom was changing was the shift in job responsibilities. A longtime metro reporter, Linda Parker, had recently been reassigned as “online communities editor.” Every Enquirer Web page prominently featured the words “Get Published” as a way of eliciting stories, comments and anything else Cincinnatians might feel compelled to submit. It all landed in Parker’s queue; perhaps not surprisingly, these words and videos never have resembled anything commonly considered journalism.

Even figuring out how best to prompt contributors has revealed valuable lessons to those at the Enquirer—ones that other news organizations can learn from. “It used to read, ‘Be a Citizen Journalist,’” Parker told me. “And no one ever clicked on it. Then we said, ‘Tell Us Your Story,’ and still nothing. For some reason, ‘Get Published’ were the magic words.”

Now, nearly two years into the experiment, the Enquirer considers this feature to be an unequivocal success. I sat with Parker, a cheerful woman in her mid-50’s, in April of last year as she pored over several dozen submissions she had received that day. There was one written by a local custom car builder trumpeting his upcoming appearance on a BET show, and another, expressing with the intensity of emotional passion befitting the circumstance, is a notice for a play being held to raise funds for a fifth-grader’s bone marrow transplant. Parker almost never rejects anything she receives, though she scans each one for “the F-word,” and then posts it to the site. “A few years ago these would have come across the transom as press releases and been ignored,” she says.

This observation points to a central problem with Gannett’s strategy—indeed, with both the hyperlocal and crowdsourcing movements in general. Readers are content to leave the gritty aspects of reporting to journalists; they prefer to focus on content and storytelling that Nicholas Lemann, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, once characterized in The New Yorker as being the equivalent of the contents of a church newsletter.

As it turns out, Tom Callinan, the Enquirer’s editor, observed a while into the project “even ‘Get Published’ was too newspaperlike in its sound. People don’t want to get published. They want to ‘share.’” And so this is what the Web site’s button now encourages its readers to do. The results continue, as Callinan says, to tend toward “pretty fluffy stuff.”

Lessons Learned

So what are we to take away from these experiments? Readers are very interested in playing a role in the creation of their local media. They don’t necessarily want to write the news; what they want is to engage in a conversation. This doesn’t mean, however, that they don’t have valuable contributions to make. This fall, Callinan told me, readers shared with others on the Enquirer Web site news about a stabbing at a local strip club and a photograph of a theater fire. “We were able to confirm the stabbing,” he said. “We would have never known about it without the tip.” It might not be grist for a Pulitzer, but it fills the copy hole.

Nor were these key lessons lost on those of us involved in Assignment Zero. In fact, Assignment Zero’s community manager, Amanda Michel, employed the lessons of what didn’t work adeptly at her next venture, directing The Huffington Post’s effort, Off the Bus, with its citizen-generated coverage of the presidential campaign. Rather than duplicate what journalists were doing, Off the Bus leveraged its strength—namely, the size of its network of 12,000 “reporters.” With citizen correspondents spread across the nation and ready to attend smaller rallies, fundraisers and get-out-the-vote events that the national press ignored, Off the Bus found its niche.

Off the Bus became arguably the first truly successful example of crowdsourced journalism with some of its citizen reporters breaking national stories. Perhaps its most significant story was about the moment when Barack Obama, at a nonpress event fundraiser in San Francisco, made his famous comment about how rural Americans “cling to guns or religion” as an expression of their frustration. However, this reporting by Mayhill Fowler, the citizen journalist who broke this story, actually drew attention away from Off the Bus’s broader achievement. Toward the end of the campaign, Off the Bus was publishing some 50 stories a day, and Michel—with the help of her crowd—was able to write profiles of every superdelegate, perform investigations into dubious financial contributions to the campaigns, and publish compelling firsthand reports from the frontlines in the battleground states. The national press took note—and sent its kudos—but more importantly, readers noticed. Off the Bus drew 3.5 million unique visitors to its site in the month of September.

Michel achieved this because she took away valuable information from the failures of the experimentation at Assignment Zero. Rather than dictate to her contributors, she forged a new kind of journalism based on playing to their strengths. The result: Some contributors wrote op-eds, while others provided reporting that journalists at the Web site then used in weaving together investigative features, including one that explored an increase in the prescribing of hypertension medicine to African-American women during the campaign. They also contributed “distributed reporting,” in which the network of contributors performed tasks such as analyzing how local affiliates summed up the vice presidential debate. “We received reports from more than 100 media markets,” Michel said. “We really got to see how the debate was perceived in different regions.”

Is Off the Bus the future of journalism? Hardly, Michel contends, and I agree wholeheartedly. She regards Off the Bus as complimentary, not competitive, with the work done by traditional news organizations. “We didn’t want to be the AP. We think the AP does a good job. The question was what information and perspective can citizens, not reporters on the trail, offer to the public?” Nor does she claim the Off the Bus method would work with all stories. It’s easy to build such a massive network of volunteer reporters when the story is so compelling. But what happens when the topic generates far less passion, even if it is no less important—say, for example, the nutritional content in public school lunches?

The take-away message for journalists should be this: Adapt to these changes and do so quickly. “The future of content is conversation,” says Michael Maness, the Gannett executive who helped craft the company’s recent newsroom overhaul. Worth noting is that one of Gannett’s unqualified successes are the so-called “mom sites,” launched in some 80 markets. Each is overseen and operated online by a single journalist with the assignment of facilitating conversation while also providing information. “We’re moving away from mass media and moving to mass experience,” says Maness. “How we do that? We don’t know.”

Jeff Howe writes for Wired magazine and is the author of “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business,” published by Crown Business in 2008.