Few words were uttered more often during this conference than “Wall Street.” What follows are edited excerpts from various sessions, all of which focus attention on the tug that Wall Street’s demand for high profits and short-term outlook exerts on the news business.

Photo from the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

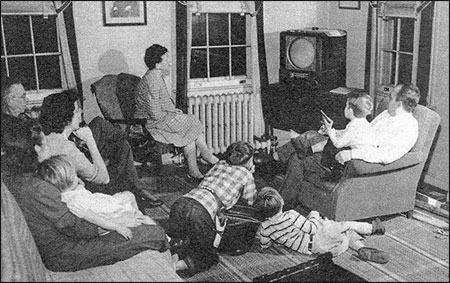

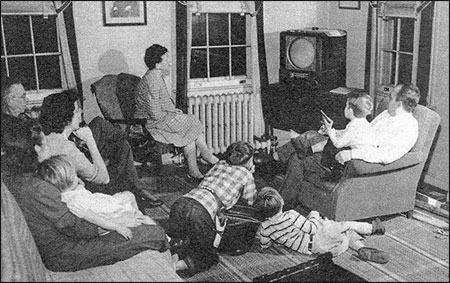

Photo from the archives of the University of Maryland Broadcast Pioneers Library of American Broadcasting, used with permission from WFAA-TV, Dallas, Texas.

Photo from the National Archives and Records Administration.

Dan Sullivan: Wall Street is very uncomfortable with newspapers because they don’t manage costs. And when they say they don’t manage costs, what they mean is they can’t complain about costs. If there are newspapers with the same size market, one will have 300 people in the newsroom while the other has 620. Those two companies can’t tell you why one is better than the other is. They can just say that it’s journalistic judgment. There’s no way in which they can walk in with some sort of concrete measure that makes sense to improve potential investment, so all of a sudden it looks like they don’t manage costs.

Alex Jones: I’d have to disagree. The Inland cost study is a constant effort to benchmark costs for every aspect of the newspaper, including the newsroom. Newspapers might be up and down on that, but the question is not whether they can manage costs but whether they can manage costs in a manner that is satisfactory and provide the earnings to Wall Street. I mean, somebody is buying the stock on the basis of liking the company. On the other hand, you’re right. It’s a news business, and when something happens the budget goes away. That’s part of the culture, especially of high quality news organizations like The New York Times. I’m sure investors in that company have been dismayed, if that’s the focus they have had, on what’s happened to the company’s earnings over the last couple of months. I just don’t agree with the way you’re describing it.

Sullivan: The way it’s framed is in terms of, “We need to be profitable so we can afford to do good journalism.” Journalism is a byproduct. “The more profitable we are, the more we can afford to do this.” But beyond that, if your business is selling audience, the rational business decision is to get a given audience at the least possible cost. That’s the way I should manage a company. Journalism is the source; it is at the center of my business. It’s not a byproduct of my business. If you want to say, “We’re going to be in the news business. That’s where our value is going to come from,” then you have to start to be able to put some measures against that. That then becomes the basis for making decisions about how to spend money because you’ve got some notion of the value it would create if you added more reporters to the story.

Bob Giles: The numbers suggest a very robust industry. As we look ahead to an uncertain economy and a period in which the primacy of news can’t be challenged, doesn’t the newspaper industry have an opportunity to change the story it tells to Wall Street and the way it presents itself to investors? Isn’t this a chance for the news industry and newspapers to create a new theme for Wall Street? Couldn’t they highlight the special place that newspapers have in our democratic life and point out the essential value of news as a long-term strategy that provides both a public service and the basis for a robust bottom line?

Eric Newton: The short answer is yes. Interest in serious news is driving all of this, and we’ll see companies moving in the direction of trying to brand themselves as quality news, as serious news, as pure news companies. And other companies that can’t or won’t will find other brands to take. What’s happening now isn’t any different than what’s been happening for several hundred years in news in this country, but it is happening with alarming speed because of the massive power of technology. I look at news a lot more like the food business: There are those companies that produce news that’s good for you and those that produce news that you might want to eat that is not that good for you.

Part of the equation we haven’t really talked about is what we teach our children about news. One hundred years ago, it used to be a requirement for statehood that a territory had to have two newspapers. The idea that the government would require newspapers today seems ridiculous. In fact, our schools don’t require media. Forty percent of our high schools either have no student media or inadequate student media. Who are these news consumers? And what are we teaching and training them to do? My little boys are primarily interested in getting all their information online. They think the daily newspaper is a cute way to read the Garfield comic in color. So when they grow up, I find it hard to believe that their first choice for information is going to be the daily printed newspaper.

There are lots of changes coming through the pipe and companies will need to brand themselves either as one with the core values of news or one with the core values of entertainment or one that seeks to amalgamate a giant audience and doesn’t really care what it uses to do that. We’ll see how they break down. We are dreaming if we think that things are going to get simpler. They’re going to get increasingly complicated with more and more and more and more choices, more brands, more confusion. And we need more education to deal with that.

Giles: Isn’t this a moment when CEO’s can go to Wall Street and say, “News is expensive, but it’s part of our obligations, part of our public trust. And we have to make these investments, the same way the drug companies have to invest in research to develop these new lines of drugs?” Isn’t this the time to do that when everybody clearly recognizes how valuable news is?

Marty Baron: We, in newsrooms, have to figure out how to manage within those resources as best we can. And on top of that we have to make the case that long-term investment in the news product ultimately has some sort of payoff that’s of value to these people who are putting pressure on us. If, in fact, long-term investment in the news does have a payoff, both in terms of additional circulation, and in terms of additional revenue, and in terms of additional profit, and finally in terms of additional profit margins, or whatever it is that’s being used to measure us, then ultimately I think that Wall Street and pension funds and people like that will say, “Okay, well, that’s the way to go.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"News in the Land of the Giants"The companies have within their power to choose the direction that they wish to go. There are many instances where families own far more than half of the company, and they can certainly make the choice that they are going to invest for the long term rather than cutting for the short term. The New York Times would be the most recognized case. Their investment in expanding their national distribution and their national presence is something that they weren’t making a lot of money on initially. In fact, the national edition of The New York Times was somewhat of an afterthought. They discovered that there was an actual business there, and all these people were willing to pay all this money to get this paper if they could only deliver it. And then they started delivering it and people paid all this money. That was long-term thinking. Various media companies have choices in which direction they wish to go. I hope they choose the route of long-term investment.

Tom Wolzien: People are looking for a steady story, in which there is stability of earnings or performance. Is this Wall Street that’s making these demands? Or how many people at this conference own mutual funds? All right, you’re to blame. How many people here put your money into bonds or into savings accounts instead of into stock? You’re to blame. What expectations do you have for the earnings? You’re expecting a certain type of return. And so these funds are deciding between company A or company B. Company A has volatile earnings and doesn’t seem to be quite in control of its costs. Company B has more stable earnings and appears to have solid control of costs. If you’re running the fund or you’re putting the money into the fund, where are you going to want your money?

So this is an issue of broad-based expectations. It’s the Street reflecting demands of the people buying the stock through the pension funds or through the mutual funds, which really are reflecting what all of us, as consumers, are demanding. So it’s a big circle. And the companies are trapped in it. Wall Street’s trapped in it. And all of us as consumers of stock or buyers who decide to put money into stock or into bank accounts are all partially responsible.

Sullivan: The old family ownership model was that people put their money into news organizations not just for the return but because they were going to make a difference; they were going to impact communities in which they lived. That was using the same kind of logic that these large, socially responsive investment funds are looking for today. But, as Tom points out, news organizations have become pure commodities on Wall Street. They have to compete against the cement company or the water company or any other kind of company for the investor’s dollar and compete on their terms because they’re not out there saying, “This is a unique investment opportunity.”

Jim Kennedy: I always get the feeling the story of the news industry was not told in a very intelligent way to Wall Street. When, as a journalist, you read the analysts’ reports on a news industry topic, you say, “Well, they’re not really getting to it.” Whereas if you’re looking at a report on the technology industry, you have a sense that these guys must know what they’re talking about. I don’t think we talk well enough about the costs and the strategy. I think that the average investor knows more about the difference in strategy between KMart and Wal-Mart than it does about Dow Jones versus The New York Times. We do have to tell the story better. We have to get at what our costs and our strategies are when we talk about them.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter: I want to know what the story is that’s being told. I hear talk about getting the story out, about the business model, but I’m not hearing anything about change, innovation, anything that makes it newsworthy. It’s more like saying, “If they only knew what we’re doing well all along, they’d value us more.” That’s what I’m hearing. I don’t know if that’s what you’re intending, but where’s the story about innovation? Where’s the story about moving with the times to provide new services of value that will give consumers something that they need in this environment? That is the story that investors are very interested in. It isn’t simply getting out a story of the status quo and support us because of that. So I was subtly saying not just what the story is but whether underneath it there’s true innovation going on—new kinds of coverage, new kinds of value being provided.

Newton: The story’s infinitely complex. To say that there’s one clean and simple story, we’re fooling ourselves. We should decide within the insanity what is the story of news, what parts we want to focus on. There are companies that are going to be making plenty of money delivering the football scores over telephone lines, and there are other companies who are going to be making lots of money doing journalism—verifying and clarifying information, providing knowledge. It would be wise of us to keep them separated and to help consumers understand the separation as well.

What we’re talking about here is whether the news companies end up owning their geographically discreet, dynamic database delivery systems or whether the delivery systems end up owning the news companies. I don’t think that the question is going to be answered by us. How much can we do? We can educate consumers better. We can encourage the government rules to favor reinvestment in news. We can stand up and beat the drum and do our own journalism.

Wolzien: On the question of investment for the future, Wall Street generally will buy demonstrable future results for a realistic story for the long term. But to sit there and say, “We’re investing for the future.” “So what are the returns going to be?” And the company says, “They’ll be good.” It doesn’t work. In crafting the story, what’s the end result of that investment? The second point is that as distribution has gotten easier, the barrier costs of entry have gotten lower and lower because you can print this stuff out on your home fax machine. There really is a growing spread between commodity news and value added. And the industry has done a fairly crappy job of differentiating between what I have in this paper or in this TV show. We’re giving you this extra stuff. And there’s a reliance on the public to make that assumption that I know I’m getting quality stuff here. Part of the story might be doing a better job of finding ways to identify what is specific to this news organization. We have these people here, other guys don’t. These are the types of stories we’re doing as opposed to the run-of-the-mill commodity news you can get other places.

Jeff Flanders: If executives are being compensated based on the stock price, if they are focused on stock options, if they are focused on short-term earnings, why is it any surprise that there is a focus on the short term? I would argue that looking at what boards are setting as compensation schemes for top media executives will tell you a lot about what they really believe in. There are a number of measures you can look at.

Phil Meyer: In his book “Corporate Irresponsibility,” Lawrence Mitchell of George Washington University, a lawyer who specializes in business issues, says the problem is structural, that short-term rewards are the problem with publicly held companies. He’s got some really interesting recommendations: He says companies shouldn’t be allowed to report quarterly; that they ought to be limited to once-a-year reports, and that boards of directors should serve for a minimum of five years so that they can’t be turned over as quickly. He also says there ought to be a stiff capital gains tax penalty for stocks held fewer than 30 days. That might bump some more long-term thinking into the system. So when we’re talking about the news business, we’re talking about problems generic to business in general because the system is structured for short-term profitability.

RELATED ARTICLE

"How to Reach Wall Street With a Different Message"

- Philip MeyerLast summer I read another book, this one by a British economics writer, David Boyle, called “The Sum of our Discontent: Why Numbers Make Us Irrational.” And his point is that we focus on things that are easy to put a number to because there is a number. Then we think it’s important because there’s a number there, and we miss a lot of important stuff that isn’t as easily quantifiable. And I thought, my God, that’s what’s happening to the news business. It’s because Wall Street is so focused on the quarterly reports, and we’ve pushed ourselves into these terrible fortunes to get the quarterly returns, and we need to do something about it.

Photo from the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Photo from the archives of the University of Maryland Broadcast Pioneers Library of American Broadcasting, used with permission from WFAA-TV, Dallas, Texas.

Photo from the National Archives and Records Administration.

Dan Sullivan: Wall Street is very uncomfortable with newspapers because they don’t manage costs. And when they say they don’t manage costs, what they mean is they can’t complain about costs. If there are newspapers with the same size market, one will have 300 people in the newsroom while the other has 620. Those two companies can’t tell you why one is better than the other is. They can just say that it’s journalistic judgment. There’s no way in which they can walk in with some sort of concrete measure that makes sense to improve potential investment, so all of a sudden it looks like they don’t manage costs.

Alex Jones: I’d have to disagree. The Inland cost study is a constant effort to benchmark costs for every aspect of the newspaper, including the newsroom. Newspapers might be up and down on that, but the question is not whether they can manage costs but whether they can manage costs in a manner that is satisfactory and provide the earnings to Wall Street. I mean, somebody is buying the stock on the basis of liking the company. On the other hand, you’re right. It’s a news business, and when something happens the budget goes away. That’s part of the culture, especially of high quality news organizations like The New York Times. I’m sure investors in that company have been dismayed, if that’s the focus they have had, on what’s happened to the company’s earnings over the last couple of months. I just don’t agree with the way you’re describing it.

Sullivan: The way it’s framed is in terms of, “We need to be profitable so we can afford to do good journalism.” Journalism is a byproduct. “The more profitable we are, the more we can afford to do this.” But beyond that, if your business is selling audience, the rational business decision is to get a given audience at the least possible cost. That’s the way I should manage a company. Journalism is the source; it is at the center of my business. It’s not a byproduct of my business. If you want to say, “We’re going to be in the news business. That’s where our value is going to come from,” then you have to start to be able to put some measures against that. That then becomes the basis for making decisions about how to spend money because you’ve got some notion of the value it would create if you added more reporters to the story.

Bob Giles: The numbers suggest a very robust industry. As we look ahead to an uncertain economy and a period in which the primacy of news can’t be challenged, doesn’t the newspaper industry have an opportunity to change the story it tells to Wall Street and the way it presents itself to investors? Isn’t this a chance for the news industry and newspapers to create a new theme for Wall Street? Couldn’t they highlight the special place that newspapers have in our democratic life and point out the essential value of news as a long-term strategy that provides both a public service and the basis for a robust bottom line?

Eric Newton: The short answer is yes. Interest in serious news is driving all of this, and we’ll see companies moving in the direction of trying to brand themselves as quality news, as serious news, as pure news companies. And other companies that can’t or won’t will find other brands to take. What’s happening now isn’t any different than what’s been happening for several hundred years in news in this country, but it is happening with alarming speed because of the massive power of technology. I look at news a lot more like the food business: There are those companies that produce news that’s good for you and those that produce news that you might want to eat that is not that good for you.

Part of the equation we haven’t really talked about is what we teach our children about news. One hundred years ago, it used to be a requirement for statehood that a territory had to have two newspapers. The idea that the government would require newspapers today seems ridiculous. In fact, our schools don’t require media. Forty percent of our high schools either have no student media or inadequate student media. Who are these news consumers? And what are we teaching and training them to do? My little boys are primarily interested in getting all their information online. They think the daily newspaper is a cute way to read the Garfield comic in color. So when they grow up, I find it hard to believe that their first choice for information is going to be the daily printed newspaper.

There are lots of changes coming through the pipe and companies will need to brand themselves either as one with the core values of news or one with the core values of entertainment or one that seeks to amalgamate a giant audience and doesn’t really care what it uses to do that. We’ll see how they break down. We are dreaming if we think that things are going to get simpler. They’re going to get increasingly complicated with more and more and more and more choices, more brands, more confusion. And we need more education to deal with that.

Giles: Isn’t this a moment when CEO’s can go to Wall Street and say, “News is expensive, but it’s part of our obligations, part of our public trust. And we have to make these investments, the same way the drug companies have to invest in research to develop these new lines of drugs?” Isn’t this the time to do that when everybody clearly recognizes how valuable news is?

Marty Baron: We, in newsrooms, have to figure out how to manage within those resources as best we can. And on top of that we have to make the case that long-term investment in the news product ultimately has some sort of payoff that’s of value to these people who are putting pressure on us. If, in fact, long-term investment in the news does have a payoff, both in terms of additional circulation, and in terms of additional revenue, and in terms of additional profit, and finally in terms of additional profit margins, or whatever it is that’s being used to measure us, then ultimately I think that Wall Street and pension funds and people like that will say, “Okay, well, that’s the way to go.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"News in the Land of the Giants"The companies have within their power to choose the direction that they wish to go. There are many instances where families own far more than half of the company, and they can certainly make the choice that they are going to invest for the long term rather than cutting for the short term. The New York Times would be the most recognized case. Their investment in expanding their national distribution and their national presence is something that they weren’t making a lot of money on initially. In fact, the national edition of The New York Times was somewhat of an afterthought. They discovered that there was an actual business there, and all these people were willing to pay all this money to get this paper if they could only deliver it. And then they started delivering it and people paid all this money. That was long-term thinking. Various media companies have choices in which direction they wish to go. I hope they choose the route of long-term investment.

Tom Wolzien: People are looking for a steady story, in which there is stability of earnings or performance. Is this Wall Street that’s making these demands? Or how many people at this conference own mutual funds? All right, you’re to blame. How many people here put your money into bonds or into savings accounts instead of into stock? You’re to blame. What expectations do you have for the earnings? You’re expecting a certain type of return. And so these funds are deciding between company A or company B. Company A has volatile earnings and doesn’t seem to be quite in control of its costs. Company B has more stable earnings and appears to have solid control of costs. If you’re running the fund or you’re putting the money into the fund, where are you going to want your money?

So this is an issue of broad-based expectations. It’s the Street reflecting demands of the people buying the stock through the pension funds or through the mutual funds, which really are reflecting what all of us, as consumers, are demanding. So it’s a big circle. And the companies are trapped in it. Wall Street’s trapped in it. And all of us as consumers of stock or buyers who decide to put money into stock or into bank accounts are all partially responsible.

Sullivan: The old family ownership model was that people put their money into news organizations not just for the return but because they were going to make a difference; they were going to impact communities in which they lived. That was using the same kind of logic that these large, socially responsive investment funds are looking for today. But, as Tom points out, news organizations have become pure commodities on Wall Street. They have to compete against the cement company or the water company or any other kind of company for the investor’s dollar and compete on their terms because they’re not out there saying, “This is a unique investment opportunity.”

Jim Kennedy: I always get the feeling the story of the news industry was not told in a very intelligent way to Wall Street. When, as a journalist, you read the analysts’ reports on a news industry topic, you say, “Well, they’re not really getting to it.” Whereas if you’re looking at a report on the technology industry, you have a sense that these guys must know what they’re talking about. I don’t think we talk well enough about the costs and the strategy. I think that the average investor knows more about the difference in strategy between KMart and Wal-Mart than it does about Dow Jones versus The New York Times. We do have to tell the story better. We have to get at what our costs and our strategies are when we talk about them.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter: I want to know what the story is that’s being told. I hear talk about getting the story out, about the business model, but I’m not hearing anything about change, innovation, anything that makes it newsworthy. It’s more like saying, “If they only knew what we’re doing well all along, they’d value us more.” That’s what I’m hearing. I don’t know if that’s what you’re intending, but where’s the story about innovation? Where’s the story about moving with the times to provide new services of value that will give consumers something that they need in this environment? That is the story that investors are very interested in. It isn’t simply getting out a story of the status quo and support us because of that. So I was subtly saying not just what the story is but whether underneath it there’s true innovation going on—new kinds of coverage, new kinds of value being provided.

Newton: The story’s infinitely complex. To say that there’s one clean and simple story, we’re fooling ourselves. We should decide within the insanity what is the story of news, what parts we want to focus on. There are companies that are going to be making plenty of money delivering the football scores over telephone lines, and there are other companies who are going to be making lots of money doing journalism—verifying and clarifying information, providing knowledge. It would be wise of us to keep them separated and to help consumers understand the separation as well.

What we’re talking about here is whether the news companies end up owning their geographically discreet, dynamic database delivery systems or whether the delivery systems end up owning the news companies. I don’t think that the question is going to be answered by us. How much can we do? We can educate consumers better. We can encourage the government rules to favor reinvestment in news. We can stand up and beat the drum and do our own journalism.

Wolzien: On the question of investment for the future, Wall Street generally will buy demonstrable future results for a realistic story for the long term. But to sit there and say, “We’re investing for the future.” “So what are the returns going to be?” And the company says, “They’ll be good.” It doesn’t work. In crafting the story, what’s the end result of that investment? The second point is that as distribution has gotten easier, the barrier costs of entry have gotten lower and lower because you can print this stuff out on your home fax machine. There really is a growing spread between commodity news and value added. And the industry has done a fairly crappy job of differentiating between what I have in this paper or in this TV show. We’re giving you this extra stuff. And there’s a reliance on the public to make that assumption that I know I’m getting quality stuff here. Part of the story might be doing a better job of finding ways to identify what is specific to this news organization. We have these people here, other guys don’t. These are the types of stories we’re doing as opposed to the run-of-the-mill commodity news you can get other places.

Jeff Flanders: If executives are being compensated based on the stock price, if they are focused on stock options, if they are focused on short-term earnings, why is it any surprise that there is a focus on the short term? I would argue that looking at what boards are setting as compensation schemes for top media executives will tell you a lot about what they really believe in. There are a number of measures you can look at.

Phil Meyer: In his book “Corporate Irresponsibility,” Lawrence Mitchell of George Washington University, a lawyer who specializes in business issues, says the problem is structural, that short-term rewards are the problem with publicly held companies. He’s got some really interesting recommendations: He says companies shouldn’t be allowed to report quarterly; that they ought to be limited to once-a-year reports, and that boards of directors should serve for a minimum of five years so that they can’t be turned over as quickly. He also says there ought to be a stiff capital gains tax penalty for stocks held fewer than 30 days. That might bump some more long-term thinking into the system. So when we’re talking about the news business, we’re talking about problems generic to business in general because the system is structured for short-term profitability.

RELATED ARTICLE

"How to Reach Wall Street With a Different Message"

- Philip MeyerLast summer I read another book, this one by a British economics writer, David Boyle, called “The Sum of our Discontent: Why Numbers Make Us Irrational.” And his point is that we focus on things that are easy to put a number to because there is a number. Then we think it’s important because there’s a number there, and we miss a lot of important stuff that isn’t as easily quantifiable. And I thought, my God, that’s what’s happening to the news business. It’s because Wall Street is so focused on the quarterly reports, and we’ve pushed ourselves into these terrible fortunes to get the quarterly returns, and we need to do something about it.

- Martin Baron has been editor of The Boston Globe since August 2001.

- Jefferson Flanders is vice president of consumer marketing at Harvard Business School Publishing, which publishes the Harvard Business Review.

- Bob Giles, a 1966 Nieman Fellow, is Curator of the Nieman Foundation.

- Alex S. Jones, a 1982 Nieman Fellow, is director of the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University.

- Rosabeth Moss Kanter is the Ernest L. Arbuckle Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School.

- Jim Kennedy is director of strategic planning at The Associated Press.

- Philip Meyer, a 1967 Nieman Fellow, is a professor of and Knight Chair in Journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Eric Newton is director of journalism initiatives at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and founding managing editor of the Newseum.

- Dan Sullivan is a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication, where he holds the Cowles Chair in Media Management and Economics.

- Tom Wolzien is senior media analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., a Wall Street research and investment management firm.