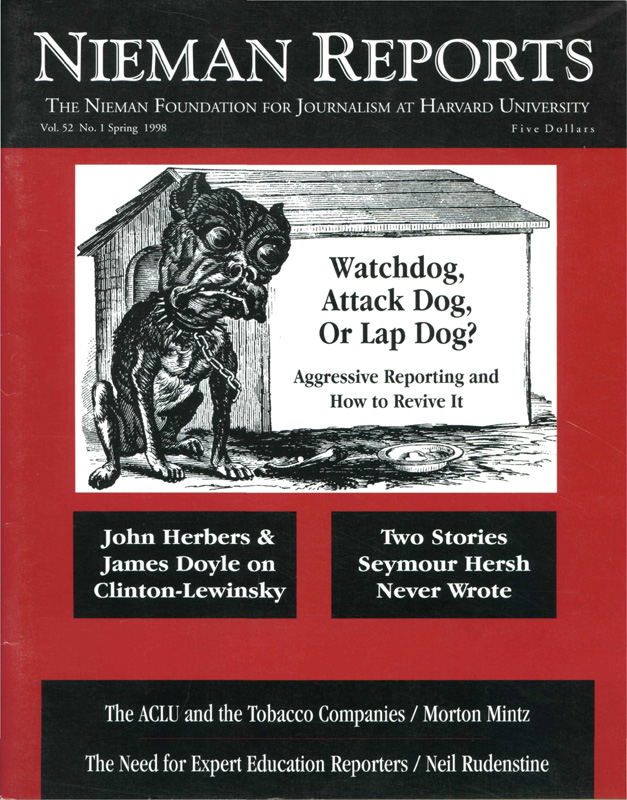

Watchdog, Attack Dog, or Lapdog?

This issue on Watchdog Journalism originated with a call by Murrey Marder, the retired Washington Post Diplomatic Correspondent, for a return to more aggressive, but responsible, reporting. The package begins with two articles on the media's handling of the accusations that President Clinton had an improper sexual relationship with Monica S. Lewinsky. Excerpts from a seminar by Seymour Hersh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter, follow. Then we offer position papers on the status of watchdog journalism in four areas—the economic sector, state and local government, national security and nonprofit organizations.

Following are edited excerpts from a discussion between Neil Rudenstine, President of Harvard University, and Nieman Fellows on December 12, 1997.

Q.—Journalism is one of the few worthy professions that Harvard doesn't teach. I wonder if you can tell us the reasoning behind not having a graduate school of journalism.

Rudenstine—I've actually read through the Harvard presidents' reports from the time at which they were first published, 1826, I think it was. I have to admit sadly that I can't recall a mention of the thought of having a journalism school. We used to have an agriculture school. We used to have a mining school. We used to have all sorts of things. We've never had a journalism school. And I don't know historically the answer to the question of why it never came up, why it was never invented. Whether it would be possible?

In theory, yes, it's possible. I wouldn't want to start one, quite honestly, with much less than somewhere between $100 and $200 million if you were going to make it good. That's about the scale you would need right now to make it any good. Of course, a new school isn't something we'd ever embark on without a great deal of discussion and planning. And here's an interesting threshold question. There is, if you will, a credentialing system in most professions—academic life, medicine, law, not all, but many. What would be a sensible credentialing system for journalism? Would you want one?

Bill Kovach, Nieman Curator, and others—The answer is no.

A.—If the answer to that is no, then what would be a good journalism school, and what would it do? I don't mean to say you couldn't have a curriculum, or you couldn't have a degree. And 1don't mean to say that one might not teach and learn a lot, because I happen to think it's a powerful, powerful set of questions that journalism raises that need to be researched, that need to be taught, that need to be thought about, that need to be tracked, etc. The Nieman program's already doing some of that; so is Marvin Kalb's program at the Kennedy School. But you know as well as 1do what would be needed to mount a really major effort to take on a whole school.

If we wouldn't want credentialing, can we say why not?

Kovach—Because it leads to licensing.

A.—In what sense, of what sort?

Kovach—Well, if you've got credentialing, someone has to pass on that credential and say yes, you're a journalist, [or] you're not. The whole notion of a free and independent press is challenged by the idea that there is somebody out there who decides who is a practitioner and who is not.

A.—What if it's your own profession that's doing it?

I'll give you an example. The academic profession is a credentialed profession, and yet it likes to think it's free, open, and so on.

Kovach—It likes to think it is. My question is, is the bar association?

A.—Well, that's different, because it doesn't have freedom of inquiry as its main tenet. That's why I chose the academic because freedom of inquiry and professional expression is at the heart of what the academic profession does. And the academic profession is in effect credentialed. But it's credentialed by its own members. The faculty of a given school evaluates quality, they vote degrees, they put forward new faculty appointments and promotions.

Kovach—But that's by institution.

A.—Yes,although there's a kind of norm across the country. It would be awfully hard in most institutions without a Ph.D.

Kovach—I'd have to think about that. That question has never been put to me.

Rudenstine—I'm not advocating it. I was just surprised at the universal negative reaction.

Kovach—The closest thing we've ever dealt with in this country so far as I know is the idea of a news council made up of, preferably, journalists, who pass judgment on performance, behavior. And that was opposed by some of the best and most powerful journalists in the country on the basis that if you take the average across the country of journalists practicing, you would have a very conservative sense of what good journalism was. [If a council like that had] been in place when the Pentagon Papers were on the table, or Watergate was under investigation, they would have said, no, don't do that. And that would have put downward pressure on your independence and your freedom. So the notion has always been, you've got to resist, if you want to remain free to pursue anything, anywhere, you've got to remain free of that kind of restriction.

A.—Actually, I would be as worried as you on that end of the spectrum. I'll give you a sense of the sorts of things that worry me, let's say, on behalf of higher education. Very,very few newspapers have actually trained people who know a lot about, think a lot about, study and understand the economics of higher education—just the economics, which are very complicated. Therefore, I can almost write for you the story every spring. Tuition goes up more than the CPI, etc. Well, actually, tuition has gone up, or the cost of higher education has quite consistently gone up more than the CPI since 1905. It's not a new thing.

[We need journalists who will] look at the economics of higher education and write the sorts of articles that journalists now write about the economics of East Asia. But so far we don't have many journalists actually investing the time to build a base of knowledge about higher education, the way others have in the political or the economic or even the scientific arena. There's good scientific reporting in The New York Times. And it's way beyond whatever you would find in higher education reporting, on an issue such as diversity in faculty hiring. There is hardly a person I talk to in the media world who has studied in detail the number of people who are going into the academic profession by race or gender. Therefore, when you get into a discussion, it's hard because there's a limited base of knowledge.

So, credentialing aside, there's a question of how best to build a base of knowledge among journalists in areas that are important to the country or to a whole set of institutions, even if we end up with different views about what should or shouldn't be done. Is there some way to somehow try to raise the investment in the media on those subjects?

Q.—It's interesting that official institutions have not discussed the foundations supporting things like education writers fellowship programs. We have fellowships for environmental reporters. We have fellowships for science reporters. There are programs like that.

A.—That's a good idea. It would be terrific. Because you know, the subject now, if you look at the GNP and see what the nation spends on education, it's not a trivial pursuit.

Q.—You're right, the quality of reporting on all levels of education, except for the largest news organizations, is very, very low on the scale. It's not a career ladder. You don't say, hey, I want to be the education reporter, because that's going to make me famous or give me the kind of clout I want or stature I want in the community. It's not going to work.

A.—Exactly. And it may never work. It just may not be the kind of subject that draws people.

Q.—In news rooms there's almost a bias against having a great deal of expertise in subjects. And I wondered in just the reading about higher education that you have—you're looking puzzled.

A.—I am puzzled. It goes against the grain of my academic—

Q.—There's this idea that you should almost dumb yourself down to be at a level of the tabula rasa so that you'll be like the average person, if you're going to write about a topic. So instead of encouraging education on a topic, you sort of demolish it. But my question here is just in terms of what you see in writing about higher education in general. Do you detect a tone of a sort of contempt in articles about, not only Harvard, but any educational institutions that do set themselves up as icons of this other form of life, the life of knowledge and unerring vision and all that?I've detected that.

A.—I don't sense a feeling of contempt or scorn. Obviously you're going to get some of that, because any major institution is going to come in for its hard knocks. And I take that more or less as it comes. The part that worries me the most is when you have important topics, like diversity in faculty hiring, or the economics of education or student aid or the cost of higher education—where a large part of the public is vitally interested and it affects them. In a way, you get a lot of parents out there who read, "Harvard costs $30,000 next year. It went up higher than the cost of inflation." Well, that stays imprisoned in your mind. That's the headline. 1here is no headline that says student aid went up faster than fees, which [has] actually [been] the case in recent years. The amount of student aid we're providing our students [has]gone up faster than our fees have gone up,sot hat we actually have 70 percent of our undergraduates on student aid. And that piece of the headline doesn't come in. So a lot of parents go away with [the message] not just that it's expensive, but it's impossible. So we spend an enormous amount of our time out in the field trying to persuade students and their parents that they actually can afford to come to Harvard.

I have read so many stories about the Catch-22 student aid-tuition spiral. And I could show in three minutes why it is not an accurate picture. And yet,there's nobody out there.... And every time I start talking to a reporter, it takes 10 minutes to get to first base about even what the nature of the "industry" is.

Q.—Have you thought of going into journalism?

A.—My stories would be too wordy.

Q.—Journalism is one of the few worthy professions that Harvard doesn't teach. I wonder if you can tell us the reasoning behind not having a graduate school of journalism.

Rudenstine—I've actually read through the Harvard presidents' reports from the time at which they were first published, 1826, I think it was. I have to admit sadly that I can't recall a mention of the thought of having a journalism school. We used to have an agriculture school. We used to have a mining school. We used to have all sorts of things. We've never had a journalism school. And I don't know historically the answer to the question of why it never came up, why it was never invented. Whether it would be possible?

In theory, yes, it's possible. I wouldn't want to start one, quite honestly, with much less than somewhere between $100 and $200 million if you were going to make it good. That's about the scale you would need right now to make it any good. Of course, a new school isn't something we'd ever embark on without a great deal of discussion and planning. And here's an interesting threshold question. There is, if you will, a credentialing system in most professions—academic life, medicine, law, not all, but many. What would be a sensible credentialing system for journalism? Would you want one?

Bill Kovach, Nieman Curator, and others—The answer is no.

A.—If the answer to that is no, then what would be a good journalism school, and what would it do? I don't mean to say you couldn't have a curriculum, or you couldn't have a degree. And 1don't mean to say that one might not teach and learn a lot, because I happen to think it's a powerful, powerful set of questions that journalism raises that need to be researched, that need to be taught, that need to be thought about, that need to be tracked, etc. The Nieman program's already doing some of that; so is Marvin Kalb's program at the Kennedy School. But you know as well as 1do what would be needed to mount a really major effort to take on a whole school.

If we wouldn't want credentialing, can we say why not?

Kovach—Because it leads to licensing.

A.—In what sense, of what sort?

Kovach—Well, if you've got credentialing, someone has to pass on that credential and say yes, you're a journalist, [or] you're not. The whole notion of a free and independent press is challenged by the idea that there is somebody out there who decides who is a practitioner and who is not.

A.—What if it's your own profession that's doing it?

I'll give you an example. The academic profession is a credentialed profession, and yet it likes to think it's free, open, and so on.

Kovach—It likes to think it is. My question is, is the bar association?

A.—Well, that's different, because it doesn't have freedom of inquiry as its main tenet. That's why I chose the academic because freedom of inquiry and professional expression is at the heart of what the academic profession does. And the academic profession is in effect credentialed. But it's credentialed by its own members. The faculty of a given school evaluates quality, they vote degrees, they put forward new faculty appointments and promotions.

Kovach—But that's by institution.

A.—Yes,although there's a kind of norm across the country. It would be awfully hard in most institutions without a Ph.D.

Kovach—I'd have to think about that. That question has never been put to me.

Rudenstine—I'm not advocating it. I was just surprised at the universal negative reaction.

Kovach—The closest thing we've ever dealt with in this country so far as I know is the idea of a news council made up of, preferably, journalists, who pass judgment on performance, behavior. And that was opposed by some of the best and most powerful journalists in the country on the basis that if you take the average across the country of journalists practicing, you would have a very conservative sense of what good journalism was. [If a council like that had] been in place when the Pentagon Papers were on the table, or Watergate was under investigation, they would have said, no, don't do that. And that would have put downward pressure on your independence and your freedom. So the notion has always been, you've got to resist, if you want to remain free to pursue anything, anywhere, you've got to remain free of that kind of restriction.

A.—Actually, I would be as worried as you on that end of the spectrum. I'll give you a sense of the sorts of things that worry me, let's say, on behalf of higher education. Very,very few newspapers have actually trained people who know a lot about, think a lot about, study and understand the economics of higher education—just the economics, which are very complicated. Therefore, I can almost write for you the story every spring. Tuition goes up more than the CPI, etc. Well, actually, tuition has gone up, or the cost of higher education has quite consistently gone up more than the CPI since 1905. It's not a new thing.

[We need journalists who will] look at the economics of higher education and write the sorts of articles that journalists now write about the economics of East Asia. But so far we don't have many journalists actually investing the time to build a base of knowledge about higher education, the way others have in the political or the economic or even the scientific arena. There's good scientific reporting in The New York Times. And it's way beyond whatever you would find in higher education reporting, on an issue such as diversity in faculty hiring. There is hardly a person I talk to in the media world who has studied in detail the number of people who are going into the academic profession by race or gender. Therefore, when you get into a discussion, it's hard because there's a limited base of knowledge.

So, credentialing aside, there's a question of how best to build a base of knowledge among journalists in areas that are important to the country or to a whole set of institutions, even if we end up with different views about what should or shouldn't be done. Is there some way to somehow try to raise the investment in the media on those subjects?

Q.—It's interesting that official institutions have not discussed the foundations supporting things like education writers fellowship programs. We have fellowships for environmental reporters. We have fellowships for science reporters. There are programs like that.

A.—That's a good idea. It would be terrific. Because you know, the subject now, if you look at the GNP and see what the nation spends on education, it's not a trivial pursuit.

Q.—You're right, the quality of reporting on all levels of education, except for the largest news organizations, is very, very low on the scale. It's not a career ladder. You don't say, hey, I want to be the education reporter, because that's going to make me famous or give me the kind of clout I want or stature I want in the community. It's not going to work.

A.—Exactly. And it may never work. It just may not be the kind of subject that draws people.

Q.—In news rooms there's almost a bias against having a great deal of expertise in subjects. And I wondered in just the reading about higher education that you have—you're looking puzzled.

A.—I am puzzled. It goes against the grain of my academic—

Q.—There's this idea that you should almost dumb yourself down to be at a level of the tabula rasa so that you'll be like the average person, if you're going to write about a topic. So instead of encouraging education on a topic, you sort of demolish it. But my question here is just in terms of what you see in writing about higher education in general. Do you detect a tone of a sort of contempt in articles about, not only Harvard, but any educational institutions that do set themselves up as icons of this other form of life, the life of knowledge and unerring vision and all that?I've detected that.

A.—I don't sense a feeling of contempt or scorn. Obviously you're going to get some of that, because any major institution is going to come in for its hard knocks. And I take that more or less as it comes. The part that worries me the most is when you have important topics, like diversity in faculty hiring, or the economics of education or student aid or the cost of higher education—where a large part of the public is vitally interested and it affects them. In a way, you get a lot of parents out there who read, "Harvard costs $30,000 next year. It went up higher than the cost of inflation." Well, that stays imprisoned in your mind. That's the headline. 1here is no headline that says student aid went up faster than fees, which [has] actually [been] the case in recent years. The amount of student aid we're providing our students [has]gone up faster than our fees have gone up,sot hat we actually have 70 percent of our undergraduates on student aid. And that piece of the headline doesn't come in. So a lot of parents go away with [the message] not just that it's expensive, but it's impossible. So we spend an enormous amount of our time out in the field trying to persuade students and their parents that they actually can afford to come to Harvard.

I have read so many stories about the Catch-22 student aid-tuition spiral. And I could show in three minutes why it is not an accurate picture. And yet,there's nobody out there.... And every time I start talking to a reporter, it takes 10 minutes to get to first base about even what the nature of the "industry" is.

Q.—Have you thought of going into journalism?

A.—My stories would be too wordy.